(Press-News.org) For most of us, crickets are probably most recognizable by the distinctive chirping sounds males make with their wings to lure females. But some crickets living on the islands of Hawaii have effectively lost their instruments and don't make their music anymore. Now researchers report in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on May 29 that crickets living on different islands quieted their wings in different ways at almost the same time.

"There is more than one way to silence a cricket," says Nathan Bailey of the University of St Andrews. "Evolution by natural selection has produced similar adaptations from different genetic starting points in what appears to be the blink of an eye in evolutionary time."

In the Hawaiian crickets, silence arose amongst males as a way to hide from parasitoid flies that are attracted to male song. Fly larvae burrow into crickets, killing them within a week's time. Quiet crickets avoid those deadly flies and still manage to mate by positioning themselves near males in the population that do sing, Bailey explains.

At first, Bailey and his colleagues thought that silent flatwing crickets had arisen just once and subsequently migrated from one island to another. However, when they looked closely at the wings of crickets on the island of Kauai versus the island of Oahu, they noticed obvious differences in the crickets' forms.

Further experiments in the lab showed that the silent wings in both cricket populations could be traced to single, sex-linked genes. However, Sonia Pascoal, a postdoc in Bailey's laboratory, performed a genome-wide scan that showed that the genes responsible are linked to different genetic markers. Remarkably, the same trait arose at about the same time on two islands, but independently and in different underlying ways.

That makes the crickets a remarkable example of convergent evolution, the researchers say, and there is still a lot more to learn from them. Bailey's laboratory is now working to unravel the genes and developmental pathways involved, as well as their interactions with the rest of the cricket genome.

"This is an exciting opportunity to detect genomic evolution in real time in a wild system, which has usually been quite a challenge, owing to the long timescales over which evolution acts," Bailey adds. "With the crickets, we can act as relatively unobtrusive observers while the drama unfolds in the wild."

INFORMATION:

Current Biology, Pascoal et al.: "Rapid Convergent Evolution in Wild Crickets."

There's more than one way to silence a cricket

2014-05-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

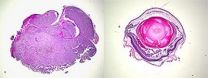

Melanoma of the eye caused by 2 gene mutations

2014-05-29

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified a therapeutic target for treating the most common form of eye cancer in adults. They have also, in experiments with mice, been able to slow eye tumor growth with an existing FDA-approved drug.

The findings are published online in the May 29 issue of the journal Cancer Cell.

"The beauty of our study is its simplicity," said Kun-Liang Guan, PhD, professor of pharmacology at UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and co-author of the study. "The genetics of this cancer are very simple ...

'Free choice' in primates altered through brain stimulation

2014-05-29

When electrical pulses are applied to the ventral tegmental area of their brain, macaques presented with two images change their preference from one image to the other. The study by researchers Wim Vanduffel and John Arsenault, KU Leuven and Massachusetts General Hospital, is the first to confirm a causal link between activity in the ventral tegmental area and choice behavior in primates.

The ventral tegmental area is located in the midbrain and helps regulate learning and reinforcement in the brain's reward system. It produces dopamine, a neurotransmitter that plays an ...

Activation of brain region can change a monkey's choice

2014-05-29

Artificially stimulating a brain region believed to play a key role in learning, reward and motivation induced monkeys to change which of two images they choose to look at. In experiments reported online in the journal Current Biology, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the University of Leuven in Belgium confirm for the first time that stimulation of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) – a group of neurons at the base of the midbrain – can change behavior through activation of the brain's reward system.

"Previous studies had correlated increased ...

Fertility: Sacrificing eggs for the greater good

2014-05-29

Baltimore, MD— A woman's supply of eggs is a precious commodity because only a few hundred mature eggs can be produced throughout her lifetime and each must be as free as possible from genetic damage. Part of egg production involves a winnowing of the egg supply during fetal development, childhood and into adulthood down from a large starting pool. New research by Carnegie's Alex Bortvin and postdoctoral fellow Safia Malki have gained new insights into the earliest stages of egg selection, which may have broad implications for women's health and fertility. The work is reported ...

NASA missions let scientists see moon's dancing tide from orbit

2014-05-29

Scientists combined observations from two NASA missions to check out the moon's lopsided shape and how it changes under Earth's sway – a response not seen from orbit before.

The team drew on studies by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been investigating the moon since 2009, and by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory, or GRAIL, mission. Because orbiting spacecraft gathered the data, the scientists were able to take the entire moon into account, not just the side that can be observed from Earth.

"The deformation of the moon due to Earth's pull ...

UNL team explores new approach to HIV vaccine

2014-05-29

Lincoln, Neb., May 29, 2014 -- Using a genetically modified form of the HIV virus, a team of University of Nebraska-Lincoln scientists has developed a promising new approach that could someday lead to a more effective HIV vaccine.

The team, led by chemist Jiantao Guo, virologist Qingsheng Li and synthetic biologist Wei Niu, has successfully tested the novel approach for vaccine development in vitro and has published findings in the international edition of the German journal Angewandte Chemie.

With the new approach, the UNL team is able to use an attenuated -- or weakened ...

A tool to better screen and treat aneurysm patients

2014-05-29

New research by an international consortium, including a researcher from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, may help physicians better understand the chronological development of a brain aneurysm.

Using radiocarbon dating to date samples of ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysm (CA) tissue, the team, led by neurosurgeon Nima Etminan, found that the main structural constituent and protein – collagen type I – in cerebral aneurysms is distinctly younger than once thought.

The new research helps identify patients more likely to suffer from an aneurysm and embark ...

Gender stereotypes keep women in the out-group

2014-05-29

New Rochelle, NY, May 29, 2014—Women have accounted for half the students in U.S. medical schools for nearly two decades, but as professors, deans, and department chairs in medical schools their numbers still lag far behind those of men. Why long-held gender stereotypes are keeping women from achieving career advancement in academic medicine and what can be done to change the institutional culture are explored in an article in Journal of Women's Health, a peer-reviewed publication from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Journal of Women's ...

Caught by a hair

2014-05-29

Crime fighters could have a new tool at their disposal following promising research by Queen's professor Diane Beauchemin.

Dr. Beauchemin (Chemistry) and student Lily Huang (MSc'15) have developed a cutting-edge technique to identify human hair. Their test is quicker than DNA analysis techniques currently used by law enforcement. Early sample testing at Queen's produced a 100 per cent success rate.

"My first paper and foray into forensic chemistry was developing a method of identifying paint that could help solve hit and run cases," explains Dr. Beauchemin. "Last year, ...

Neural transplant reduces absence epilepsy seizures in mice

2014-05-29

New research from North Carolina State University pinpoints the areas of the cerebral cortex that are affected in mice with absence epilepsy and shows that transplanting embryonic neural cells into these areas can alleviate symptoms of the disease by reducing seizure activity. The work may help identify the areas of the human brain affected in absence epilepsy and lead to new therapies for sufferers.

Absence epilepsy primarily affects children. These seizures differ from "clonic-tonic" seizures in that they don't cause muscle spasms; rather, patients "zone out" or stare ...