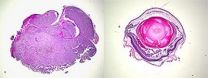

(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (May 29, 2014) – In any animal's lifecycle, the shift from egg cell to embryo is a critical juncture. This transition represents the formal initiation of development—a remarkably dynamic process that ultimately transforms a differentiated, committed oocyte to a totipotent cell capable of giving rise to any cell type in the body.

Induction of totipotency (as well as the pluripotency characteristic of embryonic stem cells) requires dramatic changes in gene expression. To date, investigations of such changes have largely focused on transcription, when DNA strands are copied into the messenger RNA (mRNA) that is subsequently translated to produce the proteins essential for proper cellular function. Yet, as Whitehead Institute Member Terry Orr-Weaver is quick to remind, at this crucial moment in life, transcription is absent.

"At the start of development, there are mechanisms other than transcription for restoring potency." Orr-Weaver says. "There are massive changes in translation accompanying the onset of development."

Recognizing the importance of translation, Orr-Weaver and her lab set out to document these "massive changes"—and their regulators—in what would be an equally massive, nearly four-year undertaking. The lab conducted perhaps the most comprehensive look yet at changes in translation and protein synthesis during a developmental change, using the oocyte-to-embryo transition in Drosophila as a model system. En route, the researchers, whose results are reported this week in the journal Cell Reports, deployed three sophisticated analytical techniques: global polysome profiling to measure active translation for thousands of mRNAs; ribosome footprint profiling to determine how efficiently each mRNA is being translated; and quantitative mass spectrometry to measure changes in protein levels at the oocyte-to-embryo transition.

"This is the first time all three pieces have been put together," Orr-Weaver says. "This comprehensive approach was crucial for gathering the insights we did."

Among those insights is the surprisingly large number of mRNAs that are translationally regulated. Approximately one thousand mRNAs were found to be upregulated, with several hundred more downregulated during this transition. Another surprise is the emergence of the protein kinase complex known as PNG as a major regulator of the observed translational changes. In earlier work, the Orr-Weaver lab had shown that the PNG kinase is necessary for the initiation of mitosis in a fertilized embryo (as opposed to the meiosis that occurs in oocytes prior to egg activation) by promoting the synthesis of Cyclin B, which is required for entry into mitosis. Subsequent work suggested that the PNG kinase's regulatory effects might be limited to activating translation of a small number of targets. This latest research, however, finds PNG acting globally, affecting translation both positively and negatively.

"For me this was unexpected," says Iva Kronja, a postdoctoral researcher in the Orr-Weaver lab and first author of the Cell Reports paper. "We knew of three mRNAs that were regulated by PNG, but these results suggest that at the oocyte-to-embryo transition, PNG controls translational status of at least 60% of translationally activated and perhaps 70% of translationally inhibited mRNAs."

Both Kronja and Orr-Weaver say this key finding shows the value of studying translation globally to record what is referred to as the "translatome". Yet the translatome provides only part of the picture. The rest is revealed through quantitative analysis of changes in the protein levels that shape the proteome. Here, too, a few surprises emerged.

The scientists discovered a set of roughly 60 mRNAs whose translation was upregulated without a corresponding increase in the levels of protein produced. This apparent paradox suggests that at the oocyte-to-embryo transition, protein degradation is occurring simultaneously with translational activation. Such compensation could maintain overall protein levels while "resetting" the proteome at restoration of totipotency, delivering proteins in a form that is optimal for embryogenesis. Kronja believes there's a quality-control aspect to this balancing act.

"I see this process as preparation for a dynamic and intense period of development," says Kronja. "Its purpose may be making sure that the right components with the right modifications are in place for embryonic development."

Orr-Weaver notes that this latest work has opened a number of new research avenues for her lab, including trying to determine whether previously unidentified proteins are regulating the switch from meiosis to mitosis at this key transitional moment.

"We found new proteins whose function has been unknown," says Orr-Weaver. "But from the dynamic changes in their levels that we observed, they may be candidates that are responsible for flipping that switch."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM39341), the American Cancer Society, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Written by Matt Fearer

Terry Orr-Weaver's primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where her laboratory is located and all her research is conducted. She is also an American Cancer Society Research Professor of biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Full Citation:

"Widespread changes in the posttranscriptional landscape at the Drosophila oocyte-to-embryo transition"

Cell Reports, May 29, 2014

Iva Kronja (1), Bingbing Yuan (1), Stephen Eichhorn (1,2,3), Kristina Dzeyk (4), Jeroen Krijgsveld (4), David P. Bartel (1,2,3), and Terry L. Orr-Weaver (1,2)

1. Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Nine Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

2. Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

3. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

4. European Molecular Biology Laboratory, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Lost in translation?

Not when it comes to control of gene expression during Drosophila development

2014-05-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

There's more than one way to silence a cricket

2014-05-29

For most of us, crickets are probably most recognizable by the distinctive chirping sounds males make with their wings to lure females. But some crickets living on the islands of Hawaii have effectively lost their instruments and don't make their music anymore. Now researchers report in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on May 29 that crickets living on different islands quieted their wings in different ways at almost the same time.

"There is more than one way to silence a cricket," says Nathan Bailey of the University of St Andrews. "Evolution by natural selection ...

Melanoma of the eye caused by 2 gene mutations

2014-05-29

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified a therapeutic target for treating the most common form of eye cancer in adults. They have also, in experiments with mice, been able to slow eye tumor growth with an existing FDA-approved drug.

The findings are published online in the May 29 issue of the journal Cancer Cell.

"The beauty of our study is its simplicity," said Kun-Liang Guan, PhD, professor of pharmacology at UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and co-author of the study. "The genetics of this cancer are very simple ...

'Free choice' in primates altered through brain stimulation

2014-05-29

When electrical pulses are applied to the ventral tegmental area of their brain, macaques presented with two images change their preference from one image to the other. The study by researchers Wim Vanduffel and John Arsenault, KU Leuven and Massachusetts General Hospital, is the first to confirm a causal link between activity in the ventral tegmental area and choice behavior in primates.

The ventral tegmental area is located in the midbrain and helps regulate learning and reinforcement in the brain's reward system. It produces dopamine, a neurotransmitter that plays an ...

Activation of brain region can change a monkey's choice

2014-05-29

Artificially stimulating a brain region believed to play a key role in learning, reward and motivation induced monkeys to change which of two images they choose to look at. In experiments reported online in the journal Current Biology, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the University of Leuven in Belgium confirm for the first time that stimulation of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) – a group of neurons at the base of the midbrain – can change behavior through activation of the brain's reward system.

"Previous studies had correlated increased ...

Fertility: Sacrificing eggs for the greater good

2014-05-29

Baltimore, MD— A woman's supply of eggs is a precious commodity because only a few hundred mature eggs can be produced throughout her lifetime and each must be as free as possible from genetic damage. Part of egg production involves a winnowing of the egg supply during fetal development, childhood and into adulthood down from a large starting pool. New research by Carnegie's Alex Bortvin and postdoctoral fellow Safia Malki have gained new insights into the earliest stages of egg selection, which may have broad implications for women's health and fertility. The work is reported ...

NASA missions let scientists see moon's dancing tide from orbit

2014-05-29

Scientists combined observations from two NASA missions to check out the moon's lopsided shape and how it changes under Earth's sway – a response not seen from orbit before.

The team drew on studies by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been investigating the moon since 2009, and by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory, or GRAIL, mission. Because orbiting spacecraft gathered the data, the scientists were able to take the entire moon into account, not just the side that can be observed from Earth.

"The deformation of the moon due to Earth's pull ...

UNL team explores new approach to HIV vaccine

2014-05-29

Lincoln, Neb., May 29, 2014 -- Using a genetically modified form of the HIV virus, a team of University of Nebraska-Lincoln scientists has developed a promising new approach that could someday lead to a more effective HIV vaccine.

The team, led by chemist Jiantao Guo, virologist Qingsheng Li and synthetic biologist Wei Niu, has successfully tested the novel approach for vaccine development in vitro and has published findings in the international edition of the German journal Angewandte Chemie.

With the new approach, the UNL team is able to use an attenuated -- or weakened ...

A tool to better screen and treat aneurysm patients

2014-05-29

New research by an international consortium, including a researcher from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, may help physicians better understand the chronological development of a brain aneurysm.

Using radiocarbon dating to date samples of ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysm (CA) tissue, the team, led by neurosurgeon Nima Etminan, found that the main structural constituent and protein – collagen type I – in cerebral aneurysms is distinctly younger than once thought.

The new research helps identify patients more likely to suffer from an aneurysm and embark ...

Gender stereotypes keep women in the out-group

2014-05-29

New Rochelle, NY, May 29, 2014—Women have accounted for half the students in U.S. medical schools for nearly two decades, but as professors, deans, and department chairs in medical schools their numbers still lag far behind those of men. Why long-held gender stereotypes are keeping women from achieving career advancement in academic medicine and what can be done to change the institutional culture are explored in an article in Journal of Women's Health, a peer-reviewed publication from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Journal of Women's ...

Caught by a hair

2014-05-29

Crime fighters could have a new tool at their disposal following promising research by Queen's professor Diane Beauchemin.

Dr. Beauchemin (Chemistry) and student Lily Huang (MSc'15) have developed a cutting-edge technique to identify human hair. Their test is quicker than DNA analysis techniques currently used by law enforcement. Early sample testing at Queen's produced a 100 per cent success rate.

"My first paper and foray into forensic chemistry was developing a method of identifying paint that could help solve hit and run cases," explains Dr. Beauchemin. "Last year, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

With the right prompts, AI chatbots analyze big data accurately

Leisure-time physical activity and cancer mortality among cancer survivors

Chronic kidney disease severity and risk of cognitive impairment

Research highlights from the first Multidisciplinary Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Symposium

New guidelines from NCCN detail fundamental differences in cancer in children compared to adults

Four NYU faculty win Sloan Foundation research fellowships

[Press-News.org] Lost in translation?Not when it comes to control of gene expression during Drosophila development