(Press-News.org) Some 56 million years ago, a massive pulse of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere sent global temperatures soaring. In the oceans, carbonate sediments dissolved, some organisms went extinct and others evolved.

Scientists have long suspected that ocean acidification played a part in the crisis—similar to today, as manmade CO2 combines with seawater to change its chemistry. Now, for the first time, scientists have quantified the extent of surface acidification from those ancient days, and the news is not good: the oceans are on track to acidify at least as much as they did then, only at a much faster rate.

In a study published in the latest issue of Paleoceanography, the scientists estimate that surface ocean acidity increased by about 100 percent in a few thousand years or more, and stayed that way for the next 70,000 years. In this radically changed environment, some creatures died out while others adapted and evolved. The study is the first to use the chemical composition of fossils to reconstruct surface ocean acidity at the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a period of intense warming on land and throughout the oceans due to high CO2.

"This could be the closest geological analog to modern ocean acidification," said study coauthor Bärbel Hönisch, a paleoceanographer at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "As massive as it was, it still happened about 10 times more slowly than what we are doing today."

The oceans have absorbed about a third of the carbon humans have pumped into the air since industrialization, helping to keep temperatures lower than they would be otherwise. But that uptake of carbon has come at a price. Chemical reactions caused by that excess CO2 have made seawater grow more acidic, depleting it of the carbonate ions that corals, mollusks and calcifying plankton need to build their shells and skeletons.

In the last 150 years or so, the pH of the oceans has dropped substantially, from 8.2 to 8.1--equivalent to a 25 percent increase in acidity. By the end of the century, ocean pH is projected to fall another 0.3 pH units, to 7.8. While the researchers found a comparable pH drop during the PETM--0.3 units--the shift happened over a few thousand years.

"We are dumping carbon in the atmosphere and ocean at a much higher rate today—within centuries," said study coauthor Richard Zeebe, a paleoceanographer at the University of Hawaii. "If we continue on the emissions path we are on right now, acidification of the surface ocean will be way more dramatic than during the PETM."

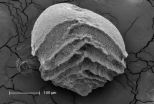

Ocean acidification in the modern ocean may already be affecting some marine life, as shown by the partly dissolved shell of this planktic snail, or pteropod, caught off the Pacific Northwest.

The study confirms that the acidified conditions lasted for 70,000 years or more, consistent with previous model-based estimates.

"It didn't bounce back right away," said Timothy Bralower, a researcher at Penn State who was not involved in the study. "It took tens of thousands of years to recover."

From seafloor sediments drilled off Japan, the researchers analyzed the shells of plankton that lived at the surface of the ocean during the PETM. Two different methods for measuring ocean chemistry at the time—the ratio of boron isotopes in their shells, and the amount of boron --arrived at similar estimates of acidification. "It's really showing us clear evidence of a change in pH for the first time," said Bralower.

What caused the burst of carbon at the PETM is still unclear. One popular explanation is that an overall warming trend may have sent a pulse of methane from the seafloor into the air, setting off events that released more earth-warming gases into the air and oceans. Up to half of the tiny animals that live in mud on the seafloor—benthic foraminifera—died out during the PETM, possibly along with life further up the food chain.

Other species thrived in this changed environment and new ones evolved. In the oceans, dinoflagellates extended their range from the tropics to the Arctic, while on land, hoofed animals and primates appeared for the first time. Eventually, the oceans and atmosphere recovered as elements from eroded rocks washed into the sea and neutralized the acid.

Today, signs are already emerging that some marine life may be in trouble. In a recent study led by Nina Bednaršedk at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, more than half of the tiny planktic snails, or pteropods, that she and her team studied off the coast of Washington, Oregon and California showed badly dissolved shells. Ocean acidification has been linked to the widespread death of baby oysters off Washington and Oregon since 2005, and may also pose a threat to coral reefs, which are under additional pressure from pollution and warming ocean temperatures.

"Seawater carbonate chemistry is complex but the mechanism underlying ocean acidification is very simple," said study lead author Donald Penman, a graduate student at University of California at Santa Cruz. "We can make accurate predictions about how carbonate chemistry will respond to increasing carbon dioxide levels. The real unknown is how individual organisms will respond and how that cascades through ecosystems."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the study, which was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation: Ellen Thomas, Yale University; and James Zachos, UC Santa Cruz

Modern ocean acidification is outpacing ancient upheaval, study suggests

Rate may be 10 times faster, according to new data

2014-06-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study: Hurricanes with female names more deadly than male-named storms

2014-06-02

In the coming Atlantic hurricane season, watch out for hurricanes with benign-sounding names like Dolly, Fay or Hanna. According to a new article from a team of researchers at the University of Illinois, hurricanes with feminine names are likely to cause significantly more deaths than hurricanes with masculine names, apparently because storms with feminine names are perceived as less threatening.

An analysis of more than six decades of death rates from U.S. hurricanes shows that severe hurricanes with a more feminine name result in a greater death toll, simply because ...

ASU researcher leads national effort to transform undergraduate biology education

2014-06-02

TEMPE, Ariz. — During the past few decades, the field of biology has dramatically expanded, incorporating many diverse sub-disciplines and specialty areas such as microbiology and evolutionary biology. However, teaching biology to undergraduate students has not kept pace with the changes, and core biology curriculum varies widely from university to university, and classroom to classroom.

In an effort to both capture the diversity of biology and condense what is taught, an Arizona State University researcher is leading a grassroots effort to improve biology education throughout ...

New UGA research engineers microbes for the direct conversion of biomass to fuel

2014-06-02

Athens, Ga. – The promise of affordable transportation fuels from biomass—a sustainable, carbon neutral route to American energy independence—has been left perpetually on hold by the economics of the conversion process. New research from the University of Georgia has overcome this hurdle allowing the direct conversion of switchgrass to fuel.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, documents the direct conversion of biomass to biofuel without pre-treatment, using the engineered bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor bescii.

Pre-treatment ...

Tracking potato famine pathogen to its home may aid $6 billion global fight

2014-06-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. – The cause of potato late blight and the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s has been tracked to a pretty, alpine valley in central Mexico, which is ringed by mountains and now known to be the ancestral home of one of the most costly and deadly plant diseases in human history.

Research published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by researchers from Oregon State University, the USDA Agricultural Research Service and five other institutions, concludes that Phytophthora infestans originated in this valley and co-evolved with potatoes ...

Tumor size is defining factor to response from promising melanoma drug

2014-06-02

CHICAGO — In examining why some advanced melanoma patients respond so well to the experimental immunotherapy MK-3475, while others have a less robust response, researchers at Mayo Clinic in Florida found that the size of tumors before treatment was the strongest variable.

MULTIMEDIA ALERT: Video and audio are available for download on the Mayo Clinic News Network.

They say their findings, being presented June 2 at the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), offered several clinical insights that could lead to different treatment strategies ...

Anti-diabetic drug slows aging and lengthens lifespan

2014-06-02

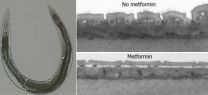

A study by Belgian doctoral researcher Wouter De Haes (KU Leuven) and colleagues provides new evidence that metformin, the world's most widely used anti-diabetic drug, slows ageing and increases lifespan.

In experiments reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers tease out the mechanism behind metformin's age-slowing effects: the drug causes an increase in the number of toxic oxygen molecules released in the cell and this, surprisingly, increases cell robustness and longevity in the long term.

Mitochondria – the energy factories ...

Marijuana shows potential in treating autoimmune disease

2014-06-02

A team of University of South Carolina researchers led by Mitzi Nagarkatti, Prakash Nagarkatti and Xiaoming Yang have discovered a novel pathway through which marijuana can suppress the body's immune functions. Their research has been published online in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Marijuana is the most frequently used illicit drug in the United States, but as more states legalize the drug for medical and even recreational purposes, research studies like this one are discovering new and innovative potential health applications for the federal Schedule I drug. ...

Shape matters...

2014-06-02

Which look bigger, packages of complicated shape or packages of simple shape? Some prior research shows that complex packages appear larger than simple packages of equal volume, while other research has shown the opposite - that simple packages look bigger than the more complex. US researchers, writing in the International Journal of Management Practice believe they have resolved this dilemma.

Lawrence Garber of Elon University in North Carolina and Eva Hyatt and Ünal Boya of Appalachian State University report that human beings are just not very good at estimating the ...

Carnegie Mellon researchers discover social integration improves lung function in elderly

2014-06-02

PITTSBURGH—It is well established that being involved in more social roles, such as being married, having close friends, close family members, and belonging to social and religious groups, leads to better mental and physical health. However, why social integration — the total number of social roles in which a person participates — influences health and longevity has not been clear.

New research led by Carnegie Mellon University shows for the first time that social integration impacts pulmonary function in the elderly. Lung function, which decreases with age, is an important ...

Study suggests fast food cues hurt ability to savor experience

2014-06-02

Toronto – Want to be able to smell the roses?

You might consider buying into a neighbourhood where there are more sit-down restaurants than fast-food outlets, suggests a new paper from the University of Toronto's Rotman School of Management.

The paper looks at how exposure to fast food can push us to be more impatient and that this can undermine our ability to smell the preverbal roses.

One study, surveyed a few hundred respondents throughout the US on their ability to savor a variety of realistic, enjoyable experiences such as discovering a beautiful waterfall on ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop an innovative prussian-blue based electrode for effective and efficient cesium removal

Self-organization of cell-sized chiral rotating actin rings driven by a chiral myosin

Report: US history polarizes generations, but has potential to unite

Tiny bubbles, big breakthrough: Cracking cancer’s “fortress”

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

How can you rescue a “kidnapped” robot? A new AI system helps the robot regain its sense of location in dynamic, ever-changing environments

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

[Press-News.org] Modern ocean acidification is outpacing ancient upheaval, study suggestsRate may be 10 times faster, according to new data