(Press-News.org) In the most comprehensive genetic study of the Mexican population to date, researchers from UC San Francisco and Stanford University, along with Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), have identified tremendous genetic diversity, reflecting thousands of years of separation among local populations and shedding light on a range of confounding aspects of Latino health.

The study, which documented nearly 1 million genetic variants among more than 1,000 individuals, unveiled genetic differences as extensive as the variations between some Europeans and Asians, indicating populations that have been isolated for hundreds to thousands of years.

These differences offer an explanation for the wide variety of health factors among Latinos of Mexican descent, including differing rates of breast cancer and asthma, as well as therapeutic response. Results of the study, on which UCSF and Stanford shared both first and senior authors, appear in the June 13, 2014 online edition of the journal Science.

"Over thousands of years, there's been a tremendous language and cultural diversity across Mexico, with large empires like the Aztec and Maya, as well as small, isolated populations," said Christopher Gignoux, PhD, who was first author on the study with Andres Moreno-Estrada, first as a graduate student at UCSF and now as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford. "Not only were we able to measure this diversity across the country, but we identified tremendous genetic diversity, with real disease implications based on where, precisely, your ancestors are from in Mexico."

For decades, physicians have based a range of diagnoses on patients' stated or perceived ethnic heritage, including baseline measurements for lung capacity, which are used to assess whether a patients' lungs are damaged by disease or environmental factors. In that context, categories such as Latino or African-American, both of which reflect people of diverse combinations of genetic ancestry, can be dangerously misleading and cause both misdiagnoses and incorrect treatment.

While there have been numerous disease/gene studies since the Human Genome Project, they have primarily focused on European and European-American populations, the researchers said. As a result, there is very little knowledge of the genetic basis for health differences among diverse populations.

"In lung disease such as asthma or emphysema, we know that it matters what ancestry you have at specific locations on your genes," said Esteban González Burchard, M.D., M.P.H., professor of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, and of Medicine, in the UCSF schools of Pharmacy and Medicine. Burchard is co-senior author of the paper with Carlos Bustamante, PhD, a professor of genetics at Stanford. "In this study, we realized that for disease classification it also matters what type of Native American ancestry you have. In terms of genetics, it's the difference between a neighborhood and a precise street address."

The researchers focused on Mexico as one of the largest sources of pre-Columbian diversity, with a long history of complex civilizations that have had varying contributions to the present-day population. Working collaboratively across the institutions, the team enlisted 40 experts, ranging from bi-lingual anthropologists to statistical geneticists, computational biologists and clinicians, as well as researchers from multiple institutions in Mexico and others in England, France, Puerto Rico and Spain.

The study covered most geographic regions in Mexico and represented 511 people from 20 indigenous and 11 mestizo (ethnically mixed) populations. Their information was compared to genetic and lung-measurement data from two previous studies, including roughly 250 Mexican and Mexican-American children in the Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans (GALA) study, the largest genetic study of Latino children in the United States, which Burchard leads.

Among the results was the discovery of three distinct genetic clusters in different areas of Mexico, as well as clear remnants of ancient empires that cross seemingly remote geographical zones. In particular, the Seri people along the northern mainland coast of the Gulf of California and a Mayan people known as the Lacandon, near the Guatemalan border, are as genetically different from one another as Europeans are from Chinese.

"We were surprised by the fact that this composition was also reflected in people with mixed ancestries from cosmopolitan areas," said co-first author Andres Moreno-Estrada, MD, PhD, a life sciences research associate at Stanford. "Hidden among the European and African ancestry blocks, the indigenous genetic map resembles a geographic map of Mexico."

The study also revealed a dramatic difference in lung capacity between mestizo individuals with western indigenous Mexican ancestry and those with eastern ancestry, to the degree that in a lung test of two equally healthy people of the same age, someone from the west could appear to be a decade younger than a Yucatan counterpart. Burchard said this was clinically significant and could have important implications in diagnosing lung disease.

Significantly, the study found that these genetic origins correlated directly to lung function in modern Mexican-Americans. As a result, the research lays the groundwork for both further research and for developing precise diagnostics and possibly even therapeutics, based on these genetic variations. It also creates a potentially important tool for public health policy, especially in Mexico, in allocating resources for both research and care.

"This can shape public health and public policy," Burchard said. "If you're testing a group of kids who are at risk for asthma or other health conditions, you want to do it in an area where the frequency of the disease gene is highest. We now have a map of Mexico that will help researchers make those clinical and public health decisions."

Burchard, a pulmonologist whose work focuses on the impact of genetic ancestry on children's risk of asthma and response to asthma medications, has wanted to study the Mexican population since 2003, both as a medical context for Mexican-Americans and as an opportunity to understand Native American genetics. To do so, he reached out to Bustamante, who directs the Stanford Center for Computational, Evolutionary and Human Genomics.

"We were particularly motivated by the fact that the vast majority of genetic studies have focused on populations of European descent," Bustamante said. "We think there are lots of opportunities for understanding the biology, as well as understanding differences in disease outcome in different parts of the world, by studying the genetics of complex disease in different populations."

Over the past few years, researchers have begun to understand that genetic variation has a very peculiar structure, Bustamante said. Some common genetic variants reach appreciable frequencies (e.g., 30-50 percent) in many of the world's populations. Most of these appear to have existed in the human gene pool at the time of the great human diasporas, including the migrations out of Africa. However, Bustamante said a "huge flurry" of other mutations have arisen since then, as human populations grew due to the advent and adoption of agriculture. These are much rarer, occurring in about 1- to 2 percent of the population, and are thought to be both more recent and relevant to health and disease. These rare variants make up the bulk of genetic alterations we see in human populations.

Many of these genetic differences already are known to have a direct impact on our risk for certain diseases, such as the BRCA gene in breast cancer, or our ability to metabolize medications. But before we can develop more precise therapies or prescribe them to the right patients, we need far more knowledge of what those variants are across diverse populations, and how they affect health.

"This is driving the ball down the field toward precision medicine," Burchard said. "We can't just clump everyone together and call them European Americans or Mexican Americans. There's been a lot of resistance to studying racially mixed populations, because they've been considered too complex. We think that offers a real scientific advantage."

INFORMATION:

Complete results and a full list of authors can be found in the paper, which appears online at Sciencemag.org. A representative chart of a diverse genome, reflecting varied heritage across one individual's genes, can be found on the Burchard Lab website.

The study was supported by the Federal Government of Mexico, Mexican Health Foundation, Gonzalo Rio Arronte Foundation, George Rosenkranz Prize for Health Care Research in Developing Countries, UCSF Chancellor's Research Fellowship, Stanford Department of Genetics, National Institutes of Health (grants GM007175, 5R01GM090087, 2R01HG003229, ES015794, GM007546, GM061390, HL004464, HL078885, HL088133, RR000083, P60MD006902 and ZIA ES49019), National Science Foundation, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Amos Medical Faculty Development Award, Sandler Foundation, America Asthma Foundation and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

UCSF is the nation's leading university exclusively focused on health. Now celebrating the 150th anniversary of its founding as a medical college, UCSF is dedicated to transforming health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy; a graduate division with world-renowned programs in the biological sciences, a preeminent biomedical research enterprise and two top-tier hospitals, UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital San Francisco. Please visit http://www.ucsf.edu.

Mexican genetics study reveals huge variation in ancestry

UCSF/Stanford team uncovers basis for health differences among Latinos

2014-06-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Father's age influences rate of evolution

2014-06-12

The offspring of chimpanzees inherit 90% of new mutations from their father, and just 10% from their mother, a finding which demonstrates how mutation differs between humans and our closest living relatives, and emphasises the importance of father's age on evolution.

Published today in Science, researchers from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics and the Biomedical Primate research Centre in the Netherlands looked at whether, in chimpanzees, there was a heightened risk of fathers passing on mutations to their children compared to humans.

In humans, each individual ...

New evidence for oceans of water deep in the Earth

2014-06-12

Researchers from Northwestern University and the University of New Mexico report evidence for potentially oceans worth of water deep beneath the United States. Though not in the familiar liquid form -- the ingredients for water are bound up in rock deep in the Earth's mantle -- the discovery may represent the planet's largest water reservoir.

The presence of liquid water on the surface is what makes our "blue planet" habitable, and scientists have long been trying to figure out just how much water may be cycling between Earth's surface and interior reservoirs through ...

With the right rehabilitation, paralyzed rats learn to grip again

2014-06-12

VIDEO:

This video depicts Restored grasping after immunotherapy and rehabilitative training.

Click here for more information.

Only if the timing, dosage and kind of rehabilitation are right can motor functions make an almost full recovery after a large stroke. Rats that were paralyzed down one side by a stroke almost managed to regain their motor functions fully if they were given the ideal combination of rehabilitative training and substances that boosted the growth of nerve fibers. ...

Unexpected origin for important parts of the nervous system

2014-06-12

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that a part of the nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, is formed in a way that is different from what researchers previously believed. In this study, which is published in the journal Science, a new phenomenon is investigated within the field of developmental biology, and the findings may lead to new medical treatments for congenital disorders of the nervous system.

Almost all of the body's functions are controlled by the autonomous, involuntary nervous system, for example the heart and blood vessels, ...

Scientists discover link between climate change and ocean currents over 6 million years

2014-06-12

Scientists have discovered a relationship between climate change and ocean currents over the past six million years after analysing an area of the Atlantic near the Strait of Gibraltar, according to research published today (Friday, 13 June) in the journal Science.

An expedition of scientists, jointly led by Dr Javier Hernandez-Molina, from the Department of Earth Sciences at Royal Holloway, University of London, examined core samples from the seabed off the coast of Spain and Portugal which provided proof of shifts of climate change over millions of years.

The team ...

Habitat fragmentation increases vulnerability to disease in wild plants

2014-06-12

Proximity to other meadows increases disease resistance in wild meadow plants, according to a study led by Anna-Liisa Laine at the University of Helsinki. The results of the study, analysing the epidemiological dynamics of a fungal pathogen in the archipelago of Finland, will be published in Science on 13 June 2014.

The study surveyed more than 4,000 Plantago lanceolata meadows and their infection status by a powdery mildew fungus in the Åland archipelago of Finland. The surveys have continued since 2001, resulting in one of the world's largest databases on disease dynamics ...

Quantum computation: Fragile yet error-free

2014-06-12

This news release is available in German and Spanish. Even computers are error-prone. The slightest disturbances may alter saved information and falsify the results of calculations. To overcome these problems, computers use specific routines to continuously detect and correct errors. This also holds true for a future quantum computer, which will require procedures for error correction as well: "Quantum phenomena are extremely fragile and error-prone. Errors can spread rapidly and severely disturb the computer," says Thomas Monz, member of Rainer Blatt's research group ...

Movies with gory and disgusting scenes more likely to capture and engage audience

2014-06-12

Washington, DC (June 12, 2014) – We know it too well. We are watching a horror film and the antagonist is about to maim a character; we ball up, get ready for the shot and instead of turning away, we lean forward in the chair, then flinch and cover our eyes – Jason strikes again! But what is going on in our body that drives us to this reaction, and why do we engage in it so readily? Recent research published in the Journal of Communication found that people exposed to core disgusts (blood, guts, body products) showed higher levels of attention the more disgusting the content ...

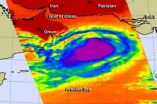

NASA takes Tropical Cyclone Nanuak's temperature

2014-06-12

Tropical Cyclone Nanauk is holding its own for now as it moves through the Arabian Sea. NASA's Aqua satellite took its cloud top temperatures to determine its health.

In terms of infrared data viewing tropical cyclones, those with the coldest cloud top temperatures indicate that a storm is the most healthy, most robust and powerful. That's because thunderstorms that have strong uplift are pushed to the top of the troposphere where temperatures are bitter cold. Infrared data, such as that collected from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument that flies aboard ...

Findings point toward one of first therapies for Lou Gehrig's disease

2014-06-12

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Researchers have determined that a copper compound known for decades may form the basis for a therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease.

In a new study just published in the Journal of Neuroscience, scientists from Australia, the United States (Oregon), and the United Kingdom showed in laboratory animal tests that oral intake of this compound significantly extended the lifespan and improved the locomotor function of transgenic mice that are genetically engineered to develop this debilitating and terminal disease.

In humans, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] Mexican genetics study reveals huge variation in ancestryUCSF/Stanford team uncovers basis for health differences among Latinos