(Press-News.org) Scientists from the Broad Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have conducted a first-of-its-kind study that characterizes the cellular diversity within glioblastoma tumors from patients. The study, which looked at the expression of thousands of genes in individual cells from patient tumors, revealed that the cellular makeup of each tumor is more heterogeneous than previously suspected. The findings, which appear online in Science Express, will help guide future investigations into potential treatments for this devastating disease.

This is the first time a large-scale census of the individual cells residing in these brain tumors has been taken. Researchers were previously aware that the cells within a human tumor were not all the same – they could have different mutations in their genome and possibly express genes differently – and it is suspected that this diversity may contribute to drug resistance and disease recurrence. But until now, it had been difficult to quantify the extent of this diversity.

To chart such differences, the researchers used a relatively new approach called single-cell transcriptomics, which allowed them to look at gene expression patterns in each of 430 individual cells from five patients' brain tumors. These patterns, which vary from cell to cell, show which genes are switched on and which are switched off in a given cell, revealing information about the cell's nature and function.

Previous studies of glioblastoma looked at the average expression of genes across millions of cells, which were slurried together in a single sample. In some cases, this type of sampling is used to classify glioblastoma tumors into one of four recognized cancer sub-types, based on the gene expression program that is most prevalent. By examining the gene expression patterns of many individual cells, one at a time, the team was able to get a finer picture of the cellular composition of the tumors. Their study revealed that each glioblastoma tumor contains individual cells from multiple cancer sub-types, and that the distribution of these cells varies from tumor to tumor.

The study also found that the cancer cells in these tumors exist in many states. Some are stem-cell-like, suggesting they have the capacity to self-renew and may play a role in tumor regeneration even after therapy. Others are the more mature, differentiated cancer cells that make up the bulk of the tumor. But the researchers also found that many cells exist on a spectrum between these states. Existing treatments, which only target the most prevalent cells in the tumor, may miss some of these sub-populations.

"To focus on the aspects of heterogeneity that we thought could be clinically relevant, we looked primarily for distinct cell states, and found multiple sub-populations in each tumor. Clinically, what this means is that we might need to treat each tumor based on the complement of cellular sub-types it contains – not just the most prevalent one," said co-senior author Aviv Regev. Regev is a Broad Institute core member and director of the Broad's Klarman Cell Observatory, as well as an associate professor at MIT and an Early Career Scientist with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The researchers hope that these findings will help guide future investigations and approaches to treatment for glioblastoma, which is the most common and most aggressive form of brain cancer in adults.

"This is an incurable disease. There are existing therapies that may target 99 percent of the cells, but the tumors always come back. Understanding the cellular landscape can provide a blueprint for identifying new therapies that target each of the various sub-populations of cancer cells, and ultimately for tailoring such therapies to individual patient tumors," said co-senior author Bradley Bernstein. Bernstein is a senior associate member of the Broad and professor of pathology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He is also an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a principal investigator at the Broad's Klarman Cell Observatory.

In addition to Bernstein and Regev, the study was led by co-first authors Anoop Patel and Itay Tirosh, who are postdoctoral fellows in the Bernstein and Regev labs respectively, and co-senior author Mario Suvà, an assistant professor of pathology at MGH and a Broad associated scientist. The team represented a path-forging partnership between physicians and researchers from MGH's Departments of Neurosurgery and Pathology, and molecular and computational biologists at the Broad. The collaboration brought together neurosurgeons and pathologists at MGH, led by Patel and Suvà, who removed the tumors from patients and molecularly characterized the samples; Broad biologists, led by John Trombetta and Alex Shalek, who conducted the single-cell analysis; and a computational team, led by Tirosh, that analyzed the data.

The team anticipates that the method and collaborative model will be effective in characterizing other cancer tumor types. Efforts to study additional cancers using the same methodology are currently underway.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the Klarman Family Foundation, as well as the National Institutes of Health, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Other researchers who worked on the study include Shawn Gillespie, Hiraoki Wakimoto, Daniel Cahill, Brian Nahed, William Curry, Robert Martuza, David Louis, and Orit Rozenblatt-Rosen.

Patel, AP et al. "Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma." Science Express. Online June 12, 2014. DOI: 10.1126/science.1254257

About the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

The Eli and Edythe L. Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was launched in 2004 to empower this generation of creative scientists to transform medicine. The Broad Institute seeks to describe all the molecular components of life and their connections; discover the molecular basis of major human diseases; develop effective new approaches to diagnostics and therapeutics; and disseminate discoveries, tools, methods and data openly to the entire scientific community.

Founded by MIT, Harvard and its affiliated hospitals, and the visionary Los Angeles philanthropists Eli and Edythe L. Broad, the Broad Institute includes faculty, professional staff and students from throughout the MIT and Harvard biomedical research communities and beyond, with collaborations spanning over a hundred private and public institutions in more than 40 countries worldwide. For further information about the Broad Institute, go to http://www.broadinstitute.org.

Broad Institute, MGH researchers chart cellular complexity of brain tumors

Cellular makeup of glioblastoma more diverse than previously thought

2014-06-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mexican genetics study reveals huge variation in ancestry

2014-06-12

In the most comprehensive genetic study of the Mexican population to date, researchers from UC San Francisco and Stanford University, along with Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), have identified tremendous genetic diversity, reflecting thousands of years of separation among local populations and shedding light on a range of confounding aspects of Latino health.

The study, which documented nearly 1 million genetic variants among more than 1,000 individuals, unveiled genetic differences as extensive as the variations between some Europeans and Asians, ...

Father's age influences rate of evolution

2014-06-12

The offspring of chimpanzees inherit 90% of new mutations from their father, and just 10% from their mother, a finding which demonstrates how mutation differs between humans and our closest living relatives, and emphasises the importance of father's age on evolution.

Published today in Science, researchers from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics and the Biomedical Primate research Centre in the Netherlands looked at whether, in chimpanzees, there was a heightened risk of fathers passing on mutations to their children compared to humans.

In humans, each individual ...

New evidence for oceans of water deep in the Earth

2014-06-12

Researchers from Northwestern University and the University of New Mexico report evidence for potentially oceans worth of water deep beneath the United States. Though not in the familiar liquid form -- the ingredients for water are bound up in rock deep in the Earth's mantle -- the discovery may represent the planet's largest water reservoir.

The presence of liquid water on the surface is what makes our "blue planet" habitable, and scientists have long been trying to figure out just how much water may be cycling between Earth's surface and interior reservoirs through ...

With the right rehabilitation, paralyzed rats learn to grip again

2014-06-12

VIDEO:

This video depicts Restored grasping after immunotherapy and rehabilitative training.

Click here for more information.

Only if the timing, dosage and kind of rehabilitation are right can motor functions make an almost full recovery after a large stroke. Rats that were paralyzed down one side by a stroke almost managed to regain their motor functions fully if they were given the ideal combination of rehabilitative training and substances that boosted the growth of nerve fibers. ...

Unexpected origin for important parts of the nervous system

2014-06-12

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that a part of the nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, is formed in a way that is different from what researchers previously believed. In this study, which is published in the journal Science, a new phenomenon is investigated within the field of developmental biology, and the findings may lead to new medical treatments for congenital disorders of the nervous system.

Almost all of the body's functions are controlled by the autonomous, involuntary nervous system, for example the heart and blood vessels, ...

Scientists discover link between climate change and ocean currents over 6 million years

2014-06-12

Scientists have discovered a relationship between climate change and ocean currents over the past six million years after analysing an area of the Atlantic near the Strait of Gibraltar, according to research published today (Friday, 13 June) in the journal Science.

An expedition of scientists, jointly led by Dr Javier Hernandez-Molina, from the Department of Earth Sciences at Royal Holloway, University of London, examined core samples from the seabed off the coast of Spain and Portugal which provided proof of shifts of climate change over millions of years.

The team ...

Habitat fragmentation increases vulnerability to disease in wild plants

2014-06-12

Proximity to other meadows increases disease resistance in wild meadow plants, according to a study led by Anna-Liisa Laine at the University of Helsinki. The results of the study, analysing the epidemiological dynamics of a fungal pathogen in the archipelago of Finland, will be published in Science on 13 June 2014.

The study surveyed more than 4,000 Plantago lanceolata meadows and their infection status by a powdery mildew fungus in the Åland archipelago of Finland. The surveys have continued since 2001, resulting in one of the world's largest databases on disease dynamics ...

Quantum computation: Fragile yet error-free

2014-06-12

This news release is available in German and Spanish. Even computers are error-prone. The slightest disturbances may alter saved information and falsify the results of calculations. To overcome these problems, computers use specific routines to continuously detect and correct errors. This also holds true for a future quantum computer, which will require procedures for error correction as well: "Quantum phenomena are extremely fragile and error-prone. Errors can spread rapidly and severely disturb the computer," says Thomas Monz, member of Rainer Blatt's research group ...

Movies with gory and disgusting scenes more likely to capture and engage audience

2014-06-12

Washington, DC (June 12, 2014) – We know it too well. We are watching a horror film and the antagonist is about to maim a character; we ball up, get ready for the shot and instead of turning away, we lean forward in the chair, then flinch and cover our eyes – Jason strikes again! But what is going on in our body that drives us to this reaction, and why do we engage in it so readily? Recent research published in the Journal of Communication found that people exposed to core disgusts (blood, guts, body products) showed higher levels of attention the more disgusting the content ...

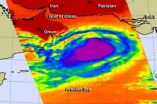

NASA takes Tropical Cyclone Nanuak's temperature

2014-06-12

Tropical Cyclone Nanauk is holding its own for now as it moves through the Arabian Sea. NASA's Aqua satellite took its cloud top temperatures to determine its health.

In terms of infrared data viewing tropical cyclones, those with the coldest cloud top temperatures indicate that a storm is the most healthy, most robust and powerful. That's because thunderstorms that have strong uplift are pushed to the top of the troposphere where temperatures are bitter cold. Infrared data, such as that collected from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument that flies aboard ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

[Press-News.org] Broad Institute, MGH researchers chart cellular complexity of brain tumorsCellular makeup of glioblastoma more diverse than previously thought