(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA—June 18, 2014 —Biologists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered a crucial process that regulates the development of blood vessels. The finding could lead to new treatments for disorders involving abnormal blood vessel growth, including common disorders such as diabetic retinopathy and cancer.

"Essentially we've shown how the protein SerRS acts as a brake on new blood vessel growth and pairs with the growth-promoting transcription factor c-Myc to bring about proper vascular development," said TSRI Professor Xiang-Lei Yang. "They act as the yin and yang of transcriptional regulation."

Yang and her colleagues reported the new findings this week in the biology journal eLife.

Multitasking Enzymes

SerRS (seryl tRNA synthetase) belongs to a family of enzymes that have fundamental, evolutionarily ancient roles in the protein-making machinery of cells. But as Yang's and other laboratories have been finding in recent years, some of these protein-maker enzymes seem to have evolved extra functions.

SerRS in particular has taken on a second basic role in animal biology. Findings from other laboratories in 2004 and 2009, mainly from genetic studies of zebrafish, first pointed to its involvement in vascular development, also known as angiogenesis. Animals with mutations to a certain part of the SerRS gene developed abnormal blood vessel systems, accompanied by excess levels of the key blood-vessel growth factor VEGFA. The implication was that SerRS somehow is needed for the proper regulation of VEGFA.

In a report published in 2012, Yang and her laboratory analyzed the portion of the SerRS protein that appears to mediate its involvement in vascular development. They found that this part of SerRS contains a special molecular homing sequence, apparently acquired several hundred million years ago during the emergence of vertebrates. The homing sequence causes a significant fraction of SerRS proteins to be transported away from the protein-making machinery of the cytoplasm and into the cell nucleus, where SerRS performs its angiogenesis-regulating function. "In that work we were able to show that SerRS's regulation of vascular development depends on the presence of this nuclear localization sequence," Yang said.

What remained to be determined was just how SerRS proteins in the nucleus regulate VEGFA. In the new study, she and her team set out to answer that question.

A Delicate Balance of Power

The scientists, including lead author Yi Shi, a staff scientist in the Yang Laboratory, started by confirming that a knockdown of nucleus-homing SerRS in human cells leads to a big jump in VEGFA production—consistent with nuclear SerRS's apparent role in suppressing VEGFA.

Shi, Yang and their colleagues then determined that SerRS binds to a "promoter region" of DNA near the VEGFA gene—in fact, to the same site where the transcription factor protein c-Myc, a known driver of new vessel growth, normally binds. The scientists were able to show that SerRS essentially competes with c-Myc for binding to this promoter region.

However, they found that SerRS does more than just elbow c-Myc aside. Whereas c-Myc promotes VEGFA transcription by adding acetyl groups to the local DNA structure, opening it up and making the gene easier to reach with transcription enzymes, SerRS has the opposite effect: It gets rid of those acetyl groups so that the local DNA closes up again. In this way more than any other, SerRS suppresses the VEGFA gene transcription that c-Myc enables.

A key finding here was that SerRS achieves this deacetylation of VEGFA DNA by recruiting a partner, the deacetylase enzyme SIRT2—which had never before been linked to angiogenesis. To confirm SIRT2's role, they knocked it down in zebrafish and found virtually the same vessel overgrowth that is seen when SerRS's nuclear-homing sequence is missing.

"Clearly the balance of influences between SerRS and c-Myc on VEGFA is important for vascular development," said Shi.

Antitumor Strategies

The new findings may end up being most relevant to antitumor strategies. SIRT2 was already considered a tumor suppressor, and c-Myc has long been known as a tumor-promoting "oncogene." A strong suggestion of this study is that SerRS, as the partner of SIRT2 in thwarting c-Myc's angiogenesis activity, may be a tumor suppressor with untapped therapeutic potential.

It may also work in that role more broadly than has been shown so far. "It has been estimated that c-Myc regulates 15 percent of human genes, so it's important to know where else SerRS opposes its activity," said Yang. "That's a clear direction for further research."

INFORMATION:

The other contributors to the paper, "tRNA synthetase counteracts c-Myc to develop functional vasculature," were Xiaoling Xu, Qian Zhang, Guangsen Fu, Zhongying Mo, George S. Wang and Shuji Kishi, all of TSRI at the time of the study. The paper is available at elifesciences.org/lookup/doi/10.7554/elife.02349

The research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (GM088278 and NS085092) and the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Scripps Research Institute scientists reveal molecular 'yin-yang' of blood vessel growth

The findings point the way to new anti-cancer strategies

2014-06-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Inflammation in fat tissue helps prevent metabolic disease

2014-06-18

DALLAS – June 18, 2014 – Chronic tissue inflammation is typically associated with obesity and metabolic disease, but new research from UT Southwestern Medical Center now finds that a level of "healthy" inflammation is necessary to prevent metabolic diseases, such as fatty liver.

"There is such a thing as 'healthy' inflammation, meaning inflammation that allows the tissue to grow and has overall benefits to the tissue itself and the whole body," said Dr. Philipp Scherer, Director of the Touchstone Center for Diabetes Research and Professor of Internal Medicine and Cell ...

Unlocking the therapeutic potential of SLC13 transporters

2014-06-18

Researchers have provided the first functional analysis of a member of a family of transporter proteins implicated in diabetes, obesity, and lifespan. The study appears in the June issue of The Journal of General Physiology.

Members of the SLC13 transporter family play a key role in the regulation of fat storage, insulin resistance, and other processes. Some SLC13 transporters mediate the transport of Krebs cycle intermediates—compounds essential for the body's metabolic activity—across the cell membrane. Previous studies have shown that loss of one member of this family ...

Penn team links placental marker of prenatal stress to brain mitochondrial dysfunction

2014-06-18

When a woman experiences a stressful event early in pregnancy, the risk of her child developing autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia increases. Yet how maternal stress is transmitted to the brain of the developing fetus, leading to these problems in neurodevelopment, is poorly understood.

New findings by University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine scientists suggest that an enzyme found in the placenta is likely playing an important role. This enzyme, O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine transferase, or OGT, translates maternal stress into a reprogramming ...

Study examines how brain 'reboots' itself to consciousness after anesthesia

2014-06-18

One of the great mysteries of anesthesia is how patients can be temporarily rendered completely unresponsive during surgery and then wake up again, with their memories and skills intact.

A new study by Dr. Andrew Hudson, an assistant professor in anesthesiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and colleagues provides important clues about the processes used by structurally normal brains to navigate from unconsciousness back to consciousness. Their findings are currently available in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...

Scripps Florida scientists pinpoint how genetic mutation causes early brain damage

2014-06-18

JUPITER, FL, June 18, 2014 – Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have shed light on how a specific kind of genetic mutation can cause damage during early brain development that results in lifelong learning and behavioral disabilities. The work suggests new possibilities for therapeutic intervention.

The study, which focuses on the role of a gene known as Syngap1, was published June 18, 2014, online ahead of print by the journal Neuron. In humans, mutations in Syngap1 are known to cause devastating forms of intellectual disability ...

Blocking brain's 'internal marijuana' may trigger early Alzheimer's deficits, study shows

2014-06-18

A new study led by investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine has implicated the blocking of endocannabinoids — signaling substances that are the brain's internal versions of the psychoactive chemicals in marijuana and hashish — in the early pathology of Alzheimer's disease.

A substance called A-beta — strongly suspected to play a key role in Alzheimer's because it's the chief constituent of the hallmark clumps dotting the brains of people with Alzheimer's — may, in the disease's earliest stages, impair learning and memory by blocking the natural, beneficial ...

Groundbreaking model explains how the brain learns to ignore familiar stimuli

2014-06-18

Dublin, June 18th, 2014 – A neuroscientist from Trinity College Dublin has proposed a new, ground-breaking explanation for the fundamental process of 'habituation', which has never been completely understood by neuroscientists.

Typically, our response to a stimulus is reduced over time if we are repeatedly exposed to it. This process of habituation enables organisms to identify and selectively ignore irrelevant, familiar objects and events that they encounter again and again. Habituation therefore allows the brain to selectively engage with new stimuli, or those that ...

Fight-or-flight chemical prepares cells to shift brain from subdued to alert

2014-06-18

A new study from The Johns Hopkins University shows that the brain cells surrounding a mouse's neurons do much more than fill space. According to the researchers, the cells, called astrocytes because of their star-shaped appearance, can monitor and respond to nearby neural activity, but only after being activated by the fight-or-flight chemical norepinephrine. Because astrocytes can alter the activity of neurons, the findings suggest that astrocytes may help control the brain's ability to focus.

The study involved observing the cells in the brains of living, active mice ...

Modeling how neurons work together

2014-06-18

A newly-developed, highly accurate representation of the way in which neurons behave when performing movements such as reaching could not only enhance understanding of the complex dynamics at work in the brain, but aid in the development of robotic limbs which are capable of more complex and natural movements.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, working in collaboration with the University of Oxford and the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), have developed a new model of a neural network, offering a novel theory of how neurons work together when ...

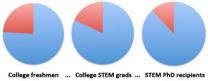

Stem pipeline problems to aid STEM diversity

2014-06-18

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Decades of effort to increase the number of minority students entering the metaphorical science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) pipeline, haven't changed this fact: Traditionally underrepresented groups remain underrepresented. In a new paper in the journal BioScience, two Brown University biologists analyze the pipeline's flawed flow and propose four research-based ideas to ensure that more students emerge from the far end with Ph.D.s and STEM careers.

Senior author Andrew G. Campbell, associate professor of biology, said ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Study: Anxiety, gloom often accompany intellectual deficits

Massage Therapy Foundation awards $300,000 research grant to the University of Denver

Gastrointestinal toxicity linked to targeted cancer therapies in the United States

Countdown to the Bial Award in Biomedicine 2025

Blood marker from dementia research could help track aging across the animal world

Birds change altitude to survive epic journeys across deserts and seas

Here's why you need a backup for the map on your phone

ACS Central Science | Researchers from Insilico Medicine and Lilly publish foundational vision for fully autonomous “Prompt-to-Drug” pharmaceutical R&D

Increasing the number of coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction does not appear to reduce death rates

Tackling uplift resistance in tall infrastructures sustainably

Novel wireless origami-inspired smart cushioning device for safer logistics

Hidden genetic mismatch, which triples the risk of a life-threatening immune attack after cord blood transplantation

Physical function is a crucial predictor of survival after heart failure

Striking genomic architecture discovered in embryonic reproductive cells before they start developing into sperm and eggs

Screening improves early detection of colorectal cancer

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

[Press-News.org] Scripps Research Institute scientists reveal molecular 'yin-yang' of blood vessel growthThe findings point the way to new anti-cancer strategies