(Press-News.org) CLEMSON, S.C. — Clemson University scientists are shedding new light on how invasion by exotic plant species affects the ability of soil to store greenhouse gases. The research could have far-reaching implications for how we manage agricultural land and native ecosystems.

In a paper published in the scientific journal New Phytologist, plant ecologist Nishanth Tharayil and graduate student Mioko Tamura show that invasive plants can accelerate the greenhouse effect by releasing carbon stored in soil into the atmosphere.

Since soil stores more carbon than both the atmosphere and terrestrial vegetation combined, the repercussions for how we manage agricultural land and ecosystems to facilitate the storage of carbon could be dramatic.

In their study, Tamura and Tharayil examined the impact of encroachment of Japanese knotweed and kudzu, two of North America's most widespread invasive plants, on the soil carbon storage in native ecosystems.

They found that kudzu invasion released carbon that was stored in native soils, while the carbon amassed in soils invaded by knotweed is more prone to oxidation and is subsequently lost to the atmosphere.

The key seems to be how plant litter chemistry regulates the soil biological activity that facilitates the buildup, composition and stability of carbon-trapping organic matter in soil.

"Our findings highlight the capacity of invasive plants to effect climate change by destabilizing the carbon pool in soil and shows that invasive plants can have profound influence on our understanding to manage land in a way that mitigates carbon emissions," Tharayil said.

Tharayil estimates that kudzu invasion results in the release of 4.8 metric tons of carbon annually, equal to the amount of carbon stored in 11.8 million acres of U.S. forest.

This is the same amount of carbon emitted annually by consuming 540 million gallons of gasoline or burning 5.1 billion pounds of coal.

"Climate change is causing massive range expansion of many exotic and invasive plant species. As the climate warms, kudzu will continue to invade northern ecosystems, and its impact on carbon emissions will grow," Tharayil said.

The findings provide particular insight into agricultural land-management strategies and suggest that it is the chemistry of plant biomass added to soil rather than the total amount of biomass that has the greatest influence on the ability of soil to harbor stable carbon.

"Our study indicates that incorporating legumes such as beans, peas, soybeans, peanuts and lentils that have a higher proportion of nitrogen in its biomass can accelerate the storage of carbon in soils," Tharayil said.

Thrarayil's lab is following up this research to gain a deeper understanding of soil carbon storage and invasion.

Tharayil leads a laboratory and research team at Clemson that studies how the chemical and biological interactions that take place in the plant-soil interface shape plant communities. He is also the director of Clemson's Multi-User Analytical Laboratory, which provides researchers with access to highly specialized laboratory instruments.

INFORMATION:

Clemson scientists: Kudzu can release soil carbon, accelerate global warming

2014-07-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cellular gates for sodium and calcium controlled by common element of ancient origin

2014-07-01

Researchers at Johns Hopkins have spotted a strong family trait in two distant relatives: The channels that permit entry of sodium and calcium ions into cells turn out to share similar means for regulating ion intake, they say. Both types of channels are critical to life. Having the right concentrations of sodium and calcium ions in cells enables healthy brain communication, heart contraction and many other processes. The new evidence is likely to aid development of drugs for channel-linked diseases ranging from epilepsy to heart ailments to muscle weakness.

"This discovery ...

Mayo Clinic: Proton therapy has advantages over IMRT for advanced head and neck cancers

2014-07-01

Rochester, Minn. -- A new study by radiation oncologists at Mayo Clinic comparing the world's literature on outcomes of proton beam therapy in the treatment of a variety of advanced head and neck cancers of the skull base compared to intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has found that proton beam therapy significantly improved disease free survival and tumor control when compared to IMRT. The results appear in the journal Lancet Oncology.

"We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the clinical outcomes of patients treated with proton therapy ...

Video games could provide venue for exploring sustainability concepts

2014-07-01

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Could playing video games help people understand and address global sustainability issues such as pollution, drought or climate change? At least two researchers believe so, outlining their argument in a concept paper published in the journal First Monday.

Video games have the potential to educate the public and encourage development of creative solutions to social, economic and environmental problems, said Oregon State University's Shawna Kelly, one of the two authors of the article.

"Video games encourage creative and strategic thinking, which could ...

Studies: Addiction starts with an overcorrection in the brain

2014-07-01

The National Institutes of Health has turned to neuroscientists at the nation's most "Stone Cold Sober" university for help finding ways to treat drug and alcohol addiction.

Brigham Young University professor Scott Steffensen and his collaborators have published three new scientific papers that detail the brain mechanisms involved with addictive substances. And the NIH thinks Steffensen's on the right track, as evidenced by a $2-million grant that will help fund projects in his BYU lab for the next five years.

"Addiction is a brain disease that could be treated like ...

New bridge design improves earthquake resistance, reduces damage and speeds construction

2014-07-01

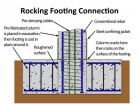

SEATTLE, Wash. - Researchers have developed a new design for the framework of columns and beams that support bridges, called "bents," to improve performance for better resistance to earthquakes, less damage and faster on-site construction.

The faster construction is achieved by pre-fabricating the columns and beams off-site and shipping them to the site, where they are erected and connected quickly.

"The design of reinforced concrete bridges in seismic regions has changed little since the mid-1970s," said John Stanton, a professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental ...

Chinese herbal extract may help kill off pancreatic cancer cells

2014-07-01

Bethesda, Md. (July 1, 2014) — A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer—the fourth most common cause of cancer death in the U.S.—can be devastating. Due in part to aggressive cell replication and tumor growth, pancreatic cancer progresses quickly and has a low five-year survival rate (less than 5 percent).

GRP78, a protein that protects cells from dying, is more abundant in cancer cells and tissue than in normal organs and is thought to play a role in helping pancreatic cancer cells survive and thrive. Researchers at the University of Minnesota have found triptolide, an extract ...

Tags reveal Chilean devil rays are among ocean's deepest divers

2014-07-01

Thought to dwell mostly near the ocean's surface, Chilean devil rays (Mobula tarapacana) are most often seen gliding through shallow, warm waters. But a new study by scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and international colleagues reveals that these large and majestic creatures are actually among the deepest-diving ocean animals.

"So little is known about these rays," said Simon Thorrold, a biologist at WHOI and one of the authors of the paper, published July 1, 2014, in the journal Nature Communications. "We thought they probably travelled long ...

Bringing the bling to antibacterials

2014-07-01

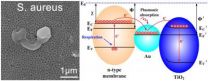

WASHINGTON D.C., July 1, 2014 – Bacteria love to colonize surfaces inside your body, but they have a hard time getting past your rugged, salty skin. Surgeries to implant medical devices often give such bacteria the opportunity needed to gain entry into the body cavity, allowing the implants themselves to act then as an ideal growing surface for biofilms.

A group of researchers at the Shanghai Institute of Ceramics in the Chinese Academy of Sciences are looking to combat these dangerous sub-dermal infections by upgrading your new hip or kneecap in a fashion appreciated ...

Efforts to cut unnecessary blood testing bring major decreases in health care spending

2014-07-01

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center used two relatively simple tactics to significantly reduce the number of unnecessary blood tests to assess symptoms of heart attack and chest pain and to achieve a large decrease in patient charges.

The team provided information and education to physicians about proven testing guidelines and made changes to the computerized provider order entry system at the medical center, part of the Johns Hopkins Health System. The guidelines call for more limited use of blood tests for so-called cardiac biomarkers. A year after implementation, ...

Separating finely mixed oil and water

2014-07-01

CAMBRIDGE, Mass-- Whenever there is a major spill of oil into water, the two tend to mix into a suspension of tiny droplets, called an emulsion, that is extremely hard to separate — and that can cause severe damage to ecosystems. But MIT researchers have discovered a new, inexpensive way of getting the two fluids apart again.

Their newly developed membrane could be manufactured at industrial scale, and could process large quantities of the finely mixed materials back into pure oil and water. The process is described in the journal Scientific Reports by MIT professor Kripa ...