(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Researchers at the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that the protein PARC/CUL9 helps neurons and brain cancer cells override the biochemical mechanisms that lead to cell death in most other cells. In neurons, long-term survival allows for proper brain function as we age. In brain cancer cells, though, long-term survival contributes to tumor growth and the spread of the disease.

These results, published in the journal Science Signaling, not only identify a previously unknown mechanism used by neurons for their much-needed survival, but show that brain cancer cells hijack the same mechanism for their own survival.

The discovery will lead to new investigations of brain cancer treatments and provides insight into Parkinson's disease, including a potential new research tool for scientists.

"PARC is very similar to Parkin, a protein that's mutated in Parkinson's disease," said Mohanish Deshmukh, a professor of cell biology and physiology and senior author of the Science Signaling paper. "We think they might work in tandem to protect neurons."

If so, researchers can investigate the interplay between these proteins to create better drugs to treat the second-most prevalent neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer's disease.

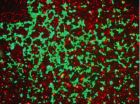

Vivian Gama, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Deshmukh's lab, led the experiments in cell cultures and animal models. First, she used external stimuli to promote the damage of mitochondria – the energy sources for cells. In most cell types, when mitochondria are damaged, they release a protein called cytochrome c, which triggers a cascade of biochemical steps that end in cell death – a process known as apoptosis.

Working with neurons, though, Gama found that the protein PARC/CUL9 blocked this process; it degraded cytochrome c, halted apoptosis, and allowed for long-term cell survival. "In this setting, we want PARC to do that because we want neurons to survive as long as possible," said Gama, first author of the Science Signaling paper.

Deshmukh, a member of the UNC Neuroscience Center and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, said, "In Parkinson's disease, we know that Parkin targets damaged mitochondria for degradation. However, exactly what happens to the proteins, such as cytochrome c, that are released from the damaged mitochondria has been unknown. Now, we think PARC plays a role in this process."

Deshmukh and Gama's work could lead to an alternative way to study Parkinson's disease. Other researchers have created mouse models that lack the Parkin gene, but Gama said these models don't have many of the hallmark symptoms that human patients have, making the model less than desirable for researchers. "Our hypothesis is that in the absence of Parkin, PARC still does the job," Gama said, "as it may allow cells to survive."

Gama and Deshmukh are now creating a model that lacks both the Parkin and PARC genes.

They will also investigate PARC as a target for cancer treatment.

"We tested several cancer cell lines and found that PARC degrades cytochrome c in medulloblastoma, a cancer of the central nervous system and in neuroblastoma, a cancer of the peripheral nervous system," Gama said. "Not all cytochrome c is degraded; there are likely other factors involved. But PARC is an important player."

When Gama and colleagues triggered the apoptotic process in brain cancer cells, they found that PARC allowed the cells to survive. When PARC was inhibited, the cells were more vulnerable to stress and damage, which means they could be more vulnerable to compounds aimed at destroying them.

Deshmukh said, "We show that brain cancer cells co-opt PARC to bypass apoptosis in the same way that neurons do and for the exact same purpose."

INFORMATION:

Other UNC co-authors include UNC post docs Vijay Swahari, PhD, and Anna Cliffe,PhD; Brian Golitz, the director of the UNC RNAi Screening Facility; pharmacology research associate Noah Sciaky; and Yue Xiong, PhD, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, the American Brain Tumor Association, and the Michael J. Fox foundation for Parkinson's research.

Neurons, brain cancer cells require the same little-known protein for long-term survival

UNC researchers lay the groundwork for a new approach to brain cancer treatments and a better understanding of Parkinson's disease

2014-07-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rollout strategy is key to battling India's TB epidemic, researchers find

2014-07-15

A new study led by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers suggests that getting patients in India quickly evaluated by the right doctors can be just as effective at curbing tuberculosis (TB) as a new, highly accurate screening test.

While ideally all suspected TB cases would be evaluated with the new test, it is primarily being used only on the highest-risk populations and only in public health clinics, partly because of its cost and the complexity of the nation's health care system. This slows diagnosis of a disease that must be caught early, the ...

New assay to spot fake malaria drugs could save thousands of lives

2014-07-15

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Chemists and students in science and engineering at Oregon State University have created a new type of chemical test, or assay, that's inexpensive, simple, and can tell whether or not one of the primary drugs being used to treat malaria is genuine – an enormous and deadly problem in the developing world.

The World Health Organization has estimated that about 200,000 lives a year may be lost due to the use of counterfeit anti-malarial drugs. When commercialized, the new OSU technology may be able to help address that problem by testing drugs for efficacy ...

3-D nanostructure could benefit nanoelectronics, gas storage

2014-07-15

A three-dimensional porous nanostructure would have a balance of strength, toughness and ability to transfer heat that could benefit nanoelectronics, gas storage and composite materials that perform multiple functions, according to engineers at Rice University.

The researchers made this prediction by using computer simulations to create a series of 3-D prototypes with boron nitride, a chemical compound made of boron and nitrogen atoms. Their findings were published online July 14 in the Journal of Physical Chemistry C.

The 3-D prototypes fuse one-dimensional boron nitride ...

TGen-led study finds likely origin of lung fungus invading Pacific Northwest

2014-07-15

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. - Cryptococcus gattii, a virulent fungus that has invaded the Pacific Northwest is highly adaptive and warrants global "public health vigilance," according to a study by an international team led by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen).

C. gattii, which likely originated in Brazil, is responsible for dozens of deaths in recent years since it was first found in 1999 on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, well outside its usual tropical habitats.

"We identified several genes that may make the outbreak strains more capable of surviving ...

Rice nanophotonics experts create powerful molecular sensor

2014-07-15

Nanophotonics experts at Rice University have created a unique sensor that amplifies the optical signature of molecules by about 100 billion times. Newly published tests found the device could accurately identify the composition and structure of individual molecules containing fewer than 20 atoms.

The new imaging method, which is described this week in the journal Nature Communications, uses a form of Raman spectroscopy in combination with an intricate but mass reproducible optical amplifier. Researchers at Rice's Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) said the single-molecule ...

SLU scientists hit 'delete': Removing regions of shape-shifting protein explains how blood clots

2014-07-15

ST. LOUIS – In results recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Saint Louis University scientists have discovered that removal of disordered sections of a protein's structure reveals the molecular mechanism of a key reaction that initiates blood clotting.

Enrico Di Cera, M.D., chair of the Edward A. Doisy department of biochemistry and molecular biology at Saint Louis University, studies thrombin, a key vitamin K-dependent blood-clotting protein, and its inactive precursor prothrombin (or coagulation factor II).

"Prothrombin is essential ...

New skin gel fights breast cancer without blood clot risk

2014-07-15

CHICAGO --- A gel form of tamoxifen applied to the breasts of women with noninvasive breast cancer reduced the growth of cancer cells to the same degree as the drug taken in oral form but with fewer side effects that deter some women from taking it, according to new Northwestern Medicine® research.

Tamoxifen is an oral drug that is used for breast cancer prevention and as therapy for non-invasive breast cancer and invasive cancer.

Because the drug was absorbed through the skin directly into breast tissue, blood levels of the drug were much lower, thus, potentially ...

Game theory model reveals vulnerable moments for cancer cells' energy production

2014-07-15

Cancer's no game, but researchers at Johns Hopkins are borrowing ideas from evolutionary game theory to learn how cells cooperate within a tumor to gather energy. Their experiments, they say, could identify the ideal time to disrupt metastatic cancer cell cooperation and make a tumor more vulnerable to anti-cancer drugs.

"The reality is that we still can't cure metastatic cancer that has spread from its primary organ and game theory adds to our efforts to attack the problem," says Kenneth J. Pienta, M.D., the Donald S. Coffey Professor of Urology at the Johns Hopkins ...

Adolescent males seek intimacy and close relationships with the opposite sex

2014-07-15

July 15, 2014 -- Teenage boys desire intimacy and sex in the context of a meaningful relationship and value trust in their partnerships, according to researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. The research provides a snapshot of the development of masculine values in adolescence, an area that has been understudied. Findings are online in the American Journal of Men's Health.

The researchers studied 33 males who ranged from 14 to 16 years of age to learn more about how their romantic and sexual relationships developed, progressed, and ended. ...

Fish oil supplements reduce incidence of cognitive decline, may improve memory function

2014-07-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. –Rhode Island Hospital researchers have completed a study that found regular use of fish oil supplements (FOS) was associated with a significant reduction in cognitive decline and brain atrophy in older adults. The study examined the relationship between FOS use during the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and indicators of cognitive decline. The findings are published online in advance of print in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia.

"At least one person is diagnosed every minute with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and despite best efforts, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Call me invasive: New evidence confirms the status of the giant Asian mantis in Europe

Scientists discover a key mechanism regulating how oxytocin is released in the mouse brain

Public and patient involvement in research is a balancing act of power

Scientists discover “bacterial constipation,” a new disease caused by gut-drying bacteria

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

[Press-News.org] Neurons, brain cancer cells require the same little-known protein for long-term survivalUNC researchers lay the groundwork for a new approach to brain cancer treatments and a better understanding of Parkinson's disease