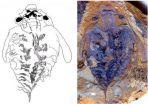

(Press-News.org) An international team of paleontologists has identified the exquisitely preserved brain in the fossil of one of the world's first known predators that lived in the Lower Cambrian, about 520 million years ago. The discovery revealed a brain that is surprisingly simple and less complex than those known from fossils of some of the animal's prey.

The find for the first time identifies the fossilized brain of what are considered the top predators of their time, a group of animals known as anomalocaridids, which translates to "abnormal shrimp." Long extinct, these fierce-looking arthropods were first discovered as fossils in the late 19th century but not properly identified until the early 1980s. They still have scientists arguing over where they belong in the tree of life.

"Our discovery helps to clarify this debate," said Nicholas Strausfeld, director of the University of Arizona's Center for Insect Science. "It turns out the top predator of the Cambrian had a brain that was much less complex than that of some of its possible prey and that looked surprisingly similar to a modern group of rather modest worm-like animals."

Strausfeld, a Regents' Professor in the Department of Neuroscience in the UA College of Science is senior author on a paper about the findings, which is scheduled for advance online publication on http://www.nature.com on July 16.

The brain in the fossil, a new species given the name Lyrarapax unguispinus – Latin for "spiny-clawed lyre-shaped predator" – suggests its relationship to a branch of animals whose living descendants are known as onychophorans or velvet worms. These wormlike animals are equipped with stubby unjointed legs that end in a pair of tiny claws.

Onychophorans, which are also exclusively predators, grow to no more than a few inches in length and are mostly found in the Southern Hemisphere, where they roam the undergrowth and leaf litter in search of beetles and other small insects, their preferred prey. Two long feelers extend from the head, attached in front of a pair of small eyes.

The anomalocaridid fossil resembles the neuroanatomy of today's onychophorans in several ways, according to Strausfeld and his collaborators. Onychophorans have a simple brain located in front of the mouth and a pair of ganglia – a collection of nerve cells – located in the front of the optic nerve and at the base of their long feelers.

"And – surprise, surprise – that is what we also found in our fossil," Strausfeld said, pointing out that anomalocaridids had a pair of clawlike grasping appendages in front of the eyes.

"These top predators in the Cambrian are defined by just their single pair of appendages, wicked-looking graspers, extending out from the front of their head," he said. "These are totally different from the antennae of insects and crustaceans. Such frontally disposed appendages are not found in any other living animals with the exception of velvet worms."

The similarities of their brains and other attributes suggest that the anomalocaridid predators could have been very distant relatives of today's velvet worms, Strausfeld said.

"This is another contribution towards the new field of research we call neuropaleontology," said Xiaoya Ma of the Natural History Museum in London, a co-author on the paper. "These grasping appendages are a characteristic feature of this most celebrated Cambrian animal group, whose affinity with living animals has troubled evolutionary scientists for almost a century. The discovery of preserved brain in Lyrarapax resolves specific anatomical correspondences with the brains of onychophorans."

"Being able to directly associate appendages with parts of the brain in Cambrian animals is a huge advantage," said co-author Gregory Edgecombe, also at the Natural History Museum. "For many years now paleontologists have struggled with the question of how different kinds of appendages in Cambrian fossils line up with each other and with what we see in living arthropods. Now for the first time, we didn't have to rely just on the external form of the appendages and their sequence in the head to try and sort out segmental identities, but we can draw on the same tool kit we use for extant arthropods – the brain."

Strausfeld and his colleagues recently presented evidence of the oldest known fossil of a brain belonging to arthropods related to insects and crustaceans and another belonging to a creature related to horseshoe crabs and scorpions (see links below).

"With this paper and our previous reports in Nature, we have identified the three principal brain arrangements that define the three groups of arthropods that exist today," Strausfeld said. "They appear to have already coexisted 520 million years ago."

The Lyrarapax fossil was found in 2013 by co-author Peiyun Cong near Kunming in the Chinese province of Yunnan. Co-authors Ma and Edgecombe participated in the analysis, as did Xianguang Hou – who discovered the Chengjiang fossil beds in 1984 ¬ – at the Yunnan Key Laboratory for Paleobiology at the University of Yunnan.

"Because its detailed morphology is exquisitely preserved, Lyrarapax is amongst the most complete anomalocaridids known so far," Cong said.

Just over five inches long, Lyrarapax was dwarfed by some of the larger anomalocaridids, which reached more than three feet in length. Paleontologists excavating lower Cambrian rocks in southern Australia found that some anomalocaridids had huge compound eyes, up to 10 times larger than the biggest dragonfly eye, befitting what must have been a highly efficient hunter, Strausfeld said.

The fact that the brain of the earliest known predator appears much simpler in shape than the previously unearthed brains of its contemporaries begs intriguing questions, according to Strausfeld, one of which is whether it is possible that predators drove the evolution of more complex brains.

"With the evolution of dedicated and highly efficient predators, the pressure was on other animals to be able to detect and recognize potential danger and rapidly coordinate escape movements. These requirements may have driven the evolution of more complex brain circuitry," Strausfeld said.

INFORMATION:

The research paper will be available online under DOI 10.1038/nature13486

Previous news releases published on EurekAlert about the fossil brains referenced in this news release:

Cambrian fossil pushes back evolution of complex brains: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2012-10/uoa-cfp100512.php

Extinct 'mega claw' creature had spider-like brain: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2013-10/uoa-ec101113.php

Brain of world's first known predators discovered

Scientists have found the fossilized remains of the brain of the world's earliest known predators, from a time when life teemed in the oceans but had not yet colonized the land

2014-07-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

One injection stops diabetes in its tracks

2014-07-16

VIDEO:

Salk scientists explain the implications of their latest finding and how the treatment reverses symptoms of type 2 diabetes in mice without side effects.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA—In mice with diet-induced diabetes—the equivalent of type 2 diabetes in humans—a single injection of the protein FGF1 is enough to restore blood sugar levels to a healthy range for more than two days. The discovery by Salk scientists, published today in the journal Nature, could ...

Study: Climate-cooling arctic lakes soak up greenhouse gases

2014-07-16

New University of Alaska Fairbanks research indicates that arctic thermokarst lakes stabilize climate change by storing more greenhouse gases than they emit into the atmosphere.

Countering a widely-held view that thawing permafrost accelerates atmospheric warming, a study published this week in the scientific journal Nature suggests arctic thermokarst lakes are 'net climate coolers' when observed over longer, millennial, time scales.

"Until now, we've only thought of thermokarst lakes as positive contributors to climate warming," says lead researcher Katey Walter Anthony, ...

Scientists find way to trap, kill malaria parasite

2014-07-16

Scientists may be able to entomb the malaria parasite in a prison of its own making, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report July 16 in Nature.

As it invades a red blood cell, the malaria parasite takes part of the host cell's membrane to build a protective compartment. To grow properly, steal nourishment and dump waste, the parasite then starts a series of major renovations that transform the red blood cell into a suitable home.

But the new research reveals the proteins that make these renovations must pass through a single pore ...

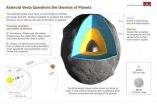

Asteroid Vesta to reshape theories of planet formation

2014-07-16

EPFL researchers have a better understanding of the asteroid Vesta and its internal structure, thanks to numerical simulations and data from the space mission Dawn. Their findings, published today in Nature, question contemporary models of rocky planet formation, including that of Earth.

With its 500 km diameter, the asteroid Vesta is one of the largest known planet embryos. It came into existence at the same time as the Solar System. Spurring scientific interest, NASA sent the Dawn spacecraft into Vesta's orbit for one year between July 2011 and July 2012.

Data gathered ...

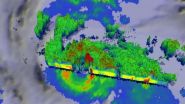

NASA sees Typhoon Rammasun exit the Philippines

2014-07-16

Typhoon Rammasun passed through the central Philippines overnight and NASA satellite imagery showed that the storm's center moved into the South China Sea. NASA's TRMM satellite showed the soaking rains that Rammasun brought to the Philippines as it tracked from east to west.

Before Rammasun made landfall, the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite passed over the storm and measured cloud heights and rainfall rates. On July 14, 2014 at 18:19 UTC (2:19 p.m. EDT), TRMM spotted powerful, high thunderstorms reaching heights of almost 17km (10.5 miles). Rain ...

Researchers demonstrate health risks posed by 'third hand' tobacco smoke

2014-07-16

Research led by the University of York has highlighted the potential cancer risk in non-smokers – particularly young children – of tobacco smoke gases and particles deposited to surfaces and dust in the home.

Until now, the risks of this exposure known as 'third hand tobacco smoke' have been highly uncertain and not considered in public policy.

However, a new study published in the journal Environment International, has estimated for the first time the potential cancer risk by age group through non-dietary ingestion and dermal exposure to third hand smoke. The results ...

Squid skin protein could improve biomedical technologies, UCI study shows

2014-07-16

Irvine, Calif., July 16, 2014 – The common pencil squid (Loliginidae) may hold the key to a new generation of medical technologies that could communicate more directly with the human body. UC Irvine materials science researchers have discovered that reflectin, a protein in the tentacled creature's skin, can conduct positive electrical charges, or protons, making it a promising material for building biologically inspired devices.

Currently, products such as retinal implants, nerve stimulators and pacemakers rely on electrons – particles with negative charges – to transmit ...

National Psoriasis Foundation awards $1.05 million in research grants

2014-07-16

PORTLAND, Ore. (July 16, 2014)—Thirteen scientists received a total of $1.05 million in funding from the National Psoriasis Foundation for projects that aim to identify new treatments and a cure for psoriasis—an autoimmune disease that appears on the skin, affecting 7.5 million Americans—and psoriatic arthritis—an inflammatory arthritis that affects the joints and tendons, occurring in up to 30 percent of people with psoriasis.

Learn more about the NPF research grant program: http://www.psoriasis.org/research.

This year, three scientists each received a two-year, $200,000 ...

70-foot-long, 52-ton concrete bridge survives series of simulated earthquakes

2014-07-16

VIDEO:

A 70-foot-long, 52-ton concrete bridge survived a series of earthquakes in the first multiple-shake-table experiment in the University of Nevada, Reno's new Earthquake Engineering Lab, the newest addition to the...

Click here for more information.

RENO, Nev. – A 70-foot-long, 52-ton concrete bridge survived a series of earthquakes in the first multiple-shake-table experiment in the University of Nevada, Reno's new Earthquake Engineering Lab, the newest addition to the ...

Dozens of fires plague Oregon

2014-07-16

Fires are a way of life during the hot, dry summer days, but that does not mean they are ever taken for granted. Thousands of lightning strikes Sunday (7/13) and early Monday (7/14) probably started most of the wildfires, which are burning on private, public and reservation land. Dozens of fires are plaguing the forest areas in the state of Oregon. In this image, are shown the Buzzard Fire, the Shaniko Butte fire, the Bridge 99 Complex fire, and the Saddle Draw Fire.

The Buzzard Complex fire began as a lightning strike. Difficult terrain, combined with extremely dry ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Brain of world's first known predators discoveredScientists have found the fossilized remains of the brain of the world's earliest known predators, from a time when life teemed in the oceans but had not yet colonized the land