(Press-News.org) Recent advances in imaging technology are transforming how scientists see the cellular universe, showing the form and movement of once grainy and blurred structures in stunning detail. But extracting the torrent of information contained in those images often surpasses the limits of existing computational and data analysis techniques, leaving scientists less than satisfied.

Now, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have developed a way around that problem. They have created a new computational method to rapidly track the three-dimensional movements of cells in such data-rich images. Using the technique, the Janelia scientists can essentially automate much of the time-consuming process of reconstructing an animal's developmental building plan cell by cell.

Philipp Keller, a group leader at Janelia, led the team that developed the computational framework. He and his colleagues, including Janelia postdoc Fernando Amat, Janelia group leader Kristin Branson and former Janelia lab head Eugene Myers, who is now at the Max Plank Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, have used the method to reconstruct cell lineage during development of the early nervous system in a fruit fly. Their method can be used to trace cell lineages in multiple organisms and efficiently processes data from multiple types of fluorescent microscopes.

The scientists describe their approach in a paper published online on July 20, 2014, in Nature Methods. Their open-source software can be downloaded for free at http://www.janelia.org/lab/keller-lab/.

In 2012, Keller developed the simultaneous multi-view (SiMView) light sheet microscope, which captures three-dimensional images with unprecedented speed and precision over periods of hours or days. The microscope's images can reveal the divisions and intricate rearrangements of individual cells as biological structures emerge in a developing embryo. Since then, Keller has been perfecting the system so he can use it to follow the development of an organism's early nervous system.

"We want to reconstruct the elemental building plan of animals, tracking each cell from very early development until late stages, so that we know everything that has happened in terms of cell movement and cell division," Keller says. "In particular, we want to understand how the nervous system forms. Ultimately, we would like to collect the developmental history of every cell in the nervous system and link that information to the cell's final function. For this purpose, we need to be able to follow individual cells on a fairly large scale and over a long period of time."

It takes more than a week for the nervous system to become functional in an embryonic mouse. Even in the fruit fly, the process takes a day. Following development for that long means Keller's team must image tens of thousands of cells at thousands of time points, and that adds up to terabytes of data. "We can get good image data sets, but if we want to reconstruct them, this is something that we can't really do without help from the computer," Keller says.

Amat, a bioinformatics specialist on Keller's team, and his colleagues have solved that problem with the new computational method that identifies and tracks dividing cells as quickly as their high-speed microscope can capture images. The process is largely automated, but incorporates a manual editing step to improve accuracy for a small percentage of cells that are difficult to track computationally.

Keller's team has been grappling with how to interpret this kind of imaging data since 2010. The problem was challenging not only because of the sheer volume of data his light sheet microscope produced, but also because of the data's complexity. Cells in a developing embryo have different shapes and behaviors and can be densely packed, making it difficult for a computer to identify and track individual cells. Inevitable variations in image quality further complicate the analysis.

Amat led the effort to develop an efficient solution. His first priority was to reduce the complexity of the data. His strategy was to first cluster the voxels (essentially three-dimensional pixels) that make up each image into larger units called supervoxels. Using a supervoxel as the smallest unit reduces an image's complexity a thousand-fold, Keller says.

Next, the program searches for ellipsoid shapes among groups of connected supervoxels, which it recognizes as cell nuclei. Once a cluster of supervoxels is identified as a cell nucleus, the computer uses that information to find the nucleus again in subsequent images. High-speed microscopy captures the images quickly enough that a single cell can't migrate very far from frame to frame. "We take advantage of that situation and use the solution from one time point as the starting point for the next point," Keller says.

"With this fairly fast, simple approach, we can solve easy cases fairly efficiently," Keller says. Those cases make up about 95 percent of the data. "In harder cases, where we might have mistakes, we use heavier machinery."

He explains that in instances where cells are harder to track – because image quality is poor or cells are crowded, for example – the computer draws on additional information. "We look at what all the cells in that neighborhood do a little bit into the future and a little bit into the past," Keller explains. Informative patterns usually emerge from that contextual information. The strategy takes more computing power than the initial tactics. "We don't want to do it for all the cells," Keller says. "But we try to crack these hard cases by gathering more information and making better informed decisions."

All of these steps can be carried out as quickly as images are acquired by the microscope, and the result is lineage information for every cell. "You know the path, you know where it is at a certain time point. You know it divided at a certain point, you know the daughter cells, you know what mother cell it came from," Keller says.

Finally, a human steps in to check the computer's work and fix any mistakes. A computer-generated "confidence score" for every cell at every time point guides the user to the small percentage of data most likely to require a human eye, making high overall accuracy possible without manual examination of each cell.

To test the power of the program, Keller's team collected images of the beginnings of the nervous system as it developed in an embryonic fruit fly. They used their method to trace the lineages of 295 neuroblasts (precursors of nerve cells) and discovered that it is possible to predict the future fate and function of many cells based on their early dynamic behavior.

Keller is eager to begin using the method to investigate a variety of questions about early development, and hopes that others will apply the approach to their own questions. To that end, the team took care to ensure that the technique can be used with a variety of data types. In addition to fruit flies, they successfully used the program to analyze images of zebrafish and mice, as well as data collected from a commercial light sheet microscope and a commercial confocal microscope.

INFORMATION:

Speedy computation enables scientists to reconstruct an animal's development cell by cell

2014-07-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Common gene variants account for most genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

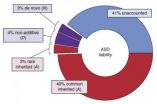

Most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have found. Heritability also outweighed other risk factors in this largest study of its kind to date.

About 52 percent of the risk for autism was traced to common and rare inherited variation, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk.

"Genetic variation likely accounts for roughly 60 percent of the liability for autism, ...

Genetic risk for autism stems mostly from common genes

2014-07-20

PITTSBURGH—Using new statistical tools, Carnegie Mellon University's Kathryn Roeder has led an international team of researchers to discover that most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches.

Published in the July 20 issue of the journal "Nature Genetics," the study found that about 52 percent of autism was traced to common genes and rarely inherited variations, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk. The research team — ...

A noble gas cage

2014-07-20

Richland, Wash. -- When nuclear fuel gets recycled, the process releases radioactive krypton and xenon gases. Naturally occurring uranium in rock contaminates basements with the related gas radon. A new porous material called CC3 effectively traps these gases, and research appearing July 20 in Nature Materials shows how: by breathing enough to let the gases in but not out.

The CC3 material could be helpful in removing unwanted or hazardous radioactive elements from nuclear fuel or air in buildings and also in recycling useful elements from the nuclear fuel cycle. CC3 ...

New method for extracting radioactive elements from air and water

2014-07-20

LIVERPOOL, UK – 20 July 2014: Scientists at the University of Liverpool have successfully tested a material that can extract atoms of rare or dangerous elements such as radon from the air.

Gases such as radon, xenon and krypton all occur naturally in the air but in minute quantities – typically less than one part per million. As a result they are expensive to extract for use in industries such as lighting or medicine and, in the case of radon, the gas can accumulate in buildings. In the US alone, radon accounts for around 21,000 lung cancer deaths a year.

Previous ...

Singapore scientists discover genetic cause of common breast tumours in women

2014-07-20

Singapore, 21 July 2014 – A multi-disciplinary team of scientists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore, and Singapore General Hospital have made a seminal breakthrough in understanding the molecular basis of fibroadenoma, one of the most common breast tumours diagnosed in women. The team, led by Professors Teh Bin Tean, Patrick Tan, Tan Puay Hoon and Steve Rozen, used advanced DNA sequencing technologies to identify a critical gene called MED12 that was repeatedly disrupted in nearly 60% of fibroadenoma cases. Their findings ...

New technique maps life's effects on our DNA

2014-07-20

Researchers at the BBSRC-funded Babraham Institute, in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Single Cell Genomics Centre, have developed a powerful new single-cell technique to help investigate how the environment affects our development and the traits we inherit from our parents. The technique can be used to map all of the 'epigenetic marks' on the DNA within a single cell. This single-cell approach will boost understanding of embryonic development, could enhance clinical applications like cancer therapy and fertility treatments, and has the potential ...

CU, Old Dominion team finds sea level rise in western tropical Pacific anthropogenic

2014-07-20

A new study led by Old Dominion University and the University of Colorado Boulder indicates sea levels likely will continue to rise in the tropical Pacific Ocean off the coasts of the Philippines and northeastern Australia as humans continue to alter the climate.

The study authors combined past sea level data gathered from both satellite altimeters and traditional tide gauges as part of the study. The goal was to find out how much a naturally occurring climate phenomenon called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, or PDO, influences sea rise patterns in the Pacific, said ...

Common gene variants account for most of the genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

Nearly 60 percent of the risk of developing autism is genetic and most of that risk is caused by inherited variant genes that are common in the population and present in individuals without the disorder, according to a study led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published in the July 20 edition of Nature Genetics.

"We show very clearly that inherited common variants comprise the bulk of the risk that sets up susceptibility to autism," says Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, the study's lead investigator and Director of the Seaver Autism Center for ...

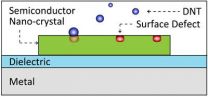

Tiny laser sensor heightens bomb detection sensitivity

2014-07-20

Berkeley — New technology under development at the University of California, Berkeley, could soon give bomb-sniffing dogs some serious competition.

A team of researchers led by Xiang Zhang, UC Berkeley professor of mechanical engineering, has found a way to dramatically increase the sensitivity of a light-based plasmon sensor to detect incredibly minute concentrations of explosives. They noted that it could potentially be used to sniff out a hard-to-detect explosive popular among terrorists.

Their findings are to be published Sunday, July 20, in the advanced online ...

Size and age of plants impact their productivity more than climate, study shows

2014-07-20

The size and age of plants has more of an impact on their productivity than temperature and precipitation, according to a landmark study by University of Arizona researchers.

UA professor Brian Enquist and postdoctoral researcher Sean Michaletz, along with collaborators Dongliang Cheng from Fujian Normal University in China and Drew Kerkhoff from Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, have combined a new mathematical theory with data from more than 1,000 forests across the world to show that climate has a relatively minor direct effect on net primary productivity, or the amount ...