(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (July 20, 2014) – A team of scientists from around the world led by Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University in St. Louis has completed the genome sequence of the common marmoset – the first sequence of a New World Monkey – providing new information about the marmoset's unique rapid reproductive system, physiology and growth, shedding new light on primate biology and evolution.

The team published the work today in the journal Nature Genetics.

"We study primate genomes to get a better understanding of the biology of the species that are most closely related to humans," said Dr. Jeffrey Rogers, associate professor in the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor and a lead author on the report. "The previous sequences of the great apes and macaques, which are very closely related to humans on the primate evolutionary tree, have provided remarkable new information about the evolutionary origins of the human genome and the processes involved."

With the sequence of the marmoset, the team revealed for the first time the genome of a non-human primate in the New World monkeys, which represents a separate branch in the primate evolutionary tree that is more distant from humans than those whose genomes have been studied in detail before. The sequence allows researchers to broaden their ability to study the human genome and its history as revealed by comparison with other primates.

The sequencing was conducted jointly by Baylor and Washington University and led by Dr. Kim Worley, professor in the Human Genome Sequencing Center, and Rogers at Baylor, and Drs. Richard K. Wilson, director, and Wesley Warren of The Genome Institute at Washington University, in collaboration with Dr. Suzette Tardif of The University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio and the Southwest National Primate Research Center.

"Each new non-human primate genome adds to a deeper understanding of human biology," said Dr. Richard Gibbs, director of the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor and a principal investigator of the study.

Twinning

The study revealed unique genetic characteristics observed in the marmoset, including several genes that are likely responsible for their ability to consistently reproduce multiple births.

"Unlike humans, marmosets consistently give birth to twins without the association of any medical issues," said Worley. "So why is it OK in marmosets but not in humans where it is considered high risk and associated with more complications?"

It turns out the marmoset gene WFIKKN1 exhibits changes associated with twinning in marmosets.

"From our analysis it appears that the gene may act as some kind of critical switch between multiples and singleton pregnancies, though it is not the only gene involved," said Rogers, who added the finding could apply to studies of multiple pregnancies in humans.

The team was also looked for genetic changes associated with a unique trait found in marmosets and their close relatives, but not described in any other mammal. The dizygotic (or fraternal) twins in marmosets exchange blood stem cells called hematopoietic stem cells in utero, which leads to chimerism, a single organism composed of genetically distinct cells.

"This is very unusual. The twins are full siblings, but if you draw a blood sample from one animal, between 10 and 50 percent of the cells will carry the sibling's DNA," said Rogers. "Normally, fraternal twins do not share the same DNA in this way, and in other animals, this chimerism can cause medical problems but not in marmosets. It is very unique."

"The translational implications of this work to pregnancy and reproductive medicine are significant. We have shown that there are several genes in the marmoset which likely enable (twinning. However, it is not just a question of why they have such a high rate of twinning, but how do they manage to rear and raise these twins so successfully," said Dr. Kjersti Aagaard, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology – maternal fetal medicine at Baylor and a co-author on the study. "Given the relatively high rate of complications of twins we see, ranging from preterm birth to unique complications such as Twin Twin Transfusion Syndrome (seen only amongst identical or monochorionic twins), it is crucial to understand the underlying adaptive biology of the marmoset which enables them to avoid these complications."

Alloparenting

Marmosets have a unique social system in which the dominant male and female serve as the primary breeders for a family, while their relatives also care for the offspring. They pick them up, carry them for long periods, and basically provide all the support allowing the breeders to reproduce again quickly. Interestingly the relatives who provide the care are reproductively suppressed, said Worley.

"This species is clearly adapted to rapid reproduction and to the potential for rapid population expansion," said Rogers. "Their ecological system connects with that as they are able to thrive in disturbed areas of forests. So one possibility is that they have evolved a feeding and dietary regimen that allows them to live in these type of conditions where they can reproduce quickly. This would be advantageous as any adults that move into a newly disturbed area would establish their offspring as the early initial residents of the newly available area."

Small body size

Marmosets also have a very small body size. The genome sequence showed this may be the result of positive selection in five growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor axis genes (GH-IGF) with potential roles in producing small body size.

Additionally, the team identified a cluster of genes that affect metabolic rates and body temperatures, adaptations associated with challenges of small body size.

MicroRNAs

The study also provides new information about microRNAs, small non-coding RNA molecules that function to regulate gene expression.

"There has not been much research conducted on microRNAs in nonhuman primates, so we found this particularly important," said Worley.

A team led by Dr. Preethi Gunaratne, an associate professor of biology and biochemistry at the University of Houston and of pathology and a member of the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor, and Dr. R. Alan Harris, an assistant professor of molecular and human genetics at Baylor, found marmosets exhibit a significant number of differences in microRNAs and their gene targets compared with humans, with two large clusters potentially involved in reproduction.

The sequence lays the foundation for further biomedical research using marmosets, said Rogers. "Researchers may have been more reluctant to study the marmoset due to lack of basic information, but this genome sequence opens new avenues for future research relevant to various aspects of human health and disease."

Dr. Suzette Tardiff, professor of cellular and structural biology at the Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, a core scientist at the Southwest National Primate Research Center and an expert in marmoset biology and co-author on the paper, provided critical information regarding the biology of marmosets, and helped obtain samples for the sequence.

INFORMATION:

Additional collaborators included researchers from Bari University in Italy; Genome Institute of Singapore; Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge; Vertebrate Genomics; European Bioinformatics Institute; Wellcome Trust Genome Campus; Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia; Wisconsin Primate Center; Indiana University; Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute in Oakland; University of Washington in Seattle; University of Geneva Medical School in Switzerland; University of Houston; University of Utah; University of Oviedo in Spain ; Wayne State University and Imperial College London in South Kensington.

Funding for this work was provided by the National Human Genome Research

Institute (U54 HG003273, U54 HG003079) with additional support from the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK077639, R01-GM59290, HG002385, P51-OD011133; National Science Foundation (NSF BCS- 0751508); VEGA grant agency; the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; the Cullen Foundation; European Research Council (260372) and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion Spain (BFU2011-28549); and Spanish the National Institute of Bioinformatics.

Glenna Picton

713-798-4710

picton@bcm.edu

http://www.bcm.edu/news

Marmoset sequence sheds new light on primate biology and evolution

2014-07-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Speedy computation enables scientists to reconstruct an animal's development cell by cell

2014-07-20

Recent advances in imaging technology are transforming how scientists see the cellular universe, showing the form and movement of once grainy and blurred structures in stunning detail. But extracting the torrent of information contained in those images often surpasses the limits of existing computational and data analysis techniques, leaving scientists less than satisfied.

Now, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have developed a way around that problem. They have created a new computational method to rapidly track the three-dimensional ...

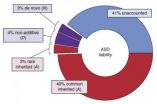

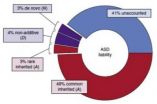

Common gene variants account for most genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

Most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health have found. Heritability also outweighed other risk factors in this largest study of its kind to date.

About 52 percent of the risk for autism was traced to common and rare inherited variation, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk.

"Genetic variation likely accounts for roughly 60 percent of the liability for autism, ...

Genetic risk for autism stems mostly from common genes

2014-07-20

PITTSBURGH—Using new statistical tools, Carnegie Mellon University's Kathryn Roeder has led an international team of researchers to discover that most of the genetic risk for autism comes from versions of genes that are common in the population rather than from rare variants or spontaneous glitches.

Published in the July 20 issue of the journal "Nature Genetics," the study found that about 52 percent of autism was traced to common genes and rarely inherited variations, with spontaneous mutations contributing a modest 2.6 percent of the total risk. The research team — ...

A noble gas cage

2014-07-20

Richland, Wash. -- When nuclear fuel gets recycled, the process releases radioactive krypton and xenon gases. Naturally occurring uranium in rock contaminates basements with the related gas radon. A new porous material called CC3 effectively traps these gases, and research appearing July 20 in Nature Materials shows how: by breathing enough to let the gases in but not out.

The CC3 material could be helpful in removing unwanted or hazardous radioactive elements from nuclear fuel or air in buildings and also in recycling useful elements from the nuclear fuel cycle. CC3 ...

New method for extracting radioactive elements from air and water

2014-07-20

LIVERPOOL, UK – 20 July 2014: Scientists at the University of Liverpool have successfully tested a material that can extract atoms of rare or dangerous elements such as radon from the air.

Gases such as radon, xenon and krypton all occur naturally in the air but in minute quantities – typically less than one part per million. As a result they are expensive to extract for use in industries such as lighting or medicine and, in the case of radon, the gas can accumulate in buildings. In the US alone, radon accounts for around 21,000 lung cancer deaths a year.

Previous ...

Singapore scientists discover genetic cause of common breast tumours in women

2014-07-20

Singapore, 21 July 2014 – A multi-disciplinary team of scientists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore, and Singapore General Hospital have made a seminal breakthrough in understanding the molecular basis of fibroadenoma, one of the most common breast tumours diagnosed in women. The team, led by Professors Teh Bin Tean, Patrick Tan, Tan Puay Hoon and Steve Rozen, used advanced DNA sequencing technologies to identify a critical gene called MED12 that was repeatedly disrupted in nearly 60% of fibroadenoma cases. Their findings ...

New technique maps life's effects on our DNA

2014-07-20

Researchers at the BBSRC-funded Babraham Institute, in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Single Cell Genomics Centre, have developed a powerful new single-cell technique to help investigate how the environment affects our development and the traits we inherit from our parents. The technique can be used to map all of the 'epigenetic marks' on the DNA within a single cell. This single-cell approach will boost understanding of embryonic development, could enhance clinical applications like cancer therapy and fertility treatments, and has the potential ...

CU, Old Dominion team finds sea level rise in western tropical Pacific anthropogenic

2014-07-20

A new study led by Old Dominion University and the University of Colorado Boulder indicates sea levels likely will continue to rise in the tropical Pacific Ocean off the coasts of the Philippines and northeastern Australia as humans continue to alter the climate.

The study authors combined past sea level data gathered from both satellite altimeters and traditional tide gauges as part of the study. The goal was to find out how much a naturally occurring climate phenomenon called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, or PDO, influences sea rise patterns in the Pacific, said ...

Common gene variants account for most of the genetic risk for autism

2014-07-20

Nearly 60 percent of the risk of developing autism is genetic and most of that risk is caused by inherited variant genes that are common in the population and present in individuals without the disorder, according to a study led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published in the July 20 edition of Nature Genetics.

"We show very clearly that inherited common variants comprise the bulk of the risk that sets up susceptibility to autism," says Joseph D. Buxbaum, PhD, the study's lead investigator and Director of the Seaver Autism Center for ...

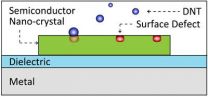

Tiny laser sensor heightens bomb detection sensitivity

2014-07-20

Berkeley — New technology under development at the University of California, Berkeley, could soon give bomb-sniffing dogs some serious competition.

A team of researchers led by Xiang Zhang, UC Berkeley professor of mechanical engineering, has found a way to dramatically increase the sensitivity of a light-based plasmon sensor to detect incredibly minute concentrations of explosives. They noted that it could potentially be used to sniff out a hard-to-detect explosive popular among terrorists.

Their findings are to be published Sunday, July 20, in the advanced online ...