(Press-News.org) Some 15% of adults suffer from fertility problems, many of these due to genetic factors. This is something of a paradox: We might expect such genes, which reduce an individual's ability to reproduce, to disappear from the population. Research at the Weizmann Institute of Science that recently appeared in Nature Communications may now have solved this riddle. Not only can it explain the high rates of male fertility problems, it may open new avenues in understanding the causes of genetic diseases and their treatment.

Various theories explain the survival of harmful mutations: A gene that today causes obesity, for example may have once granted an evolutionary advantage; or a disease-causing gene may persist because it is passed on in a small, relatively isolated population.

Dr. Moran Gershoni, a postdoctoral fellow in the group of Prof. Shmuel Pietrokovski of the Molecular Genetics Department, decided to investigate another approach – one based on differences between males and females. Although males and females carry nearly identical sets of genes, many are activated differently in each sex. So natural selection works differently on the same genes in males and females.

Take, for example, a mutation that impairs breast milk. It will undergo negative selection only in women. Conversely, a hypothetical gene variant that benefits women but is harmful to men could spread in a population, as it undergoes positive selection in half that population. Gershoni and Pietrokovski created a mathematical model for harmful mutations that affect only half the population; their model showed that these mutations should occur twice as often as those that affect males and females equally.

To test the model, the researchers searched in a computational analysis of the activities of all the human genes that appear in public databases, identifying 95 genes that are exclusively active in the testes. Most of these genes are vital for procreation; and damage to them leads, in many cases, to male sterility.

The researchers then looked at these 95 genes in people whose genomes had been made available through the 1000 Genomes Project, which gave them a broad cross-section of human populations. Their analysis revealed that genes that are active only in the testes have double the harmful mutation rate of those that are active in both sexes – right in line with the mathematical model. Pietrokovski and his team are now conducting follow-up experiments to see whether the mutations they identified do, indeed, play a role in these problems and whether the "sex-difference" approach can explain their survival.

This new understanding of the persistence of genetic mutations could yield insights into other diseases with genetic components, especially those that affect the sexes asymmetrically, including schizophrenia and Parkinson's, which are more likely to affect men, and depression and autoimmune diseases, which affect more women. And, say Gershoni and Pietrokovski, these findings highlight the need to fit even common medical treatments to the gender of the patient.

INFORMATION:

Prof. Shmuel Pietrokovski is the incumbent of the Herman and Lilly Schilling Foundation Professorial Chair.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world's top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.

Weizmann Institute news releases are posted on the World Wide Web at http://wis-wander.weizmann.ac.il, and are also available at http://www.eurekalert.org.

Mutations from Venus, mutations from Mars

2014-07-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Measuring the smallest magnets

2014-07-28

Imagine trying to measure a tennis ball that bounces wildly, every time to a distance a million times its own size. The bouncing obviously creates enormous "background noise" that interferes with the measurement. But if you attach the ball directly to a measuring device, so they bounce together, you can eliminate the noise problem.

As reported recently in Nature, physicists at the Weizmann Institute of Science used a similar trick to measure the interaction between the smallest possible magnets – two single electrons – after neutralizing magnetic noise that was a million ...

Social network research may boost prairie dog conservation efforts

2014-07-28

Researchers using statistical tools to map social connections in prairie dogs have uncovered relationships that escaped traditional observational techniques, shedding light on prairie dog communities that may help limit the spread of bubonic plague and guide future conservation efforts. The work was done by researchers from North Carolina State University and the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent).

"Prairie dogs are increasingly rare and are subject to bubonic plague," says Dr. Jennifer Verdolin, lead author of a paper on the work and an animal behavior ...

Motivation explains disconnect between testing and real-life functioning for seniors

2014-07-28

A psychology researcher at North Carolina State University is proposing a new theory to explain why older adults show declining cognitive ability with age, but don't necessarily show declines in the workplace or daily life. One key appears to be how motivated older adults are to maintain focus on cognitive tasks.

"My research team and I wanted to explain the difference we see in cognitive performance in different settings," says Dr. Tom Hess, a professor of psychology at NC State and author of a paper describing the theory. "For example, laboratory tests almost universally ...

Wearable device for the early detection of common diabetes-related neurological condition

2014-07-28

WASHINGTON, July 28, 2014—A group of researchers in Taiwan has developed a new optical technology that may be able to detect an early complication of diabetes sooner, when it is more easily treated. If the device proves safe and effective in clinical trials, it may pave the way for the early detection and more effective treatment of this complication, called diabetic autonomic neuropathy, which is common among people with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. The condition progressively affects the autonomic nerves controlling vital organs like the heart and gastrointestinal ...

Potential 'universal' blood test for cancer discovered

2014-07-28

Researchers from the University of Bradford, UK, have devised a simple blood test that can be used to diagnose whether people have cancer or not.

The test will enable doctors to rule out cancer in patients presenting with certain symptoms, saving time and preventing costly and unnecessary invasive procedures such as colonoscopies and biopsies being carried out. Alternatively, it could be a useful aid for investigating patients who are suspected of having a cancer that is currently hard to diagnose.

Early results have shown the method gives a high degree of accuracy ...

Gender inequalities in health: A matter of policies

2014-07-28

A new study of the European project SOPHIE has evaluated the relationship between the type of family policies and gender inequalities in health in Europe. The results show that countries with traditional family policies (central and southern Europe) and countries with contradictory policies (Eastern Europe), present higher inequalities in self-perceived health, i.e. women reported poorer health than men. Health inequalities are especially remarkable in Southern Europe countries, where women present a 27% higher risk of having poor health compared to men.

The authors of ...

Serial time-encoded amplified microscopy for ultrafast imaging based on multi-wavelength laser

2014-07-28

Ultrafast real-time optical imaging is an effective and important tool for studying dynamical events, such as shock waves, neural activity, laser surgery and chemical dynamics in living cells. Limited by the frame rate, conventional imaging system such as charge-coupled device (CCD) and complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) imaging device can not image fast dynamic processes. Last few years, serial time-encoded amplified microscopy (STEAM) technique based on space-frequency mapping combined with frequency-time mapping has been demonstrated as a completely new optical ...

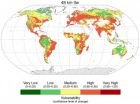

Study finds Europe's habitat and wildlife is vulnerable to climate change

2014-07-28

New research has identified areas of the Earth that are high priorities for conservation in the face of climate change.

Europe is particularly vulnerable, as it has the lowest fraction of its land area, only four per cent, of any continent in 'refugia' – areas of biological diversity that support many species where natural environmental conditions remain relatively constant during times of great environmental change. The refugia that do exist in Europe are mostly in Scandinavia and Scotland.

The biggest refugia are in the Amazon, the Congo basin, the boreal forests ...

Why do dogs smell each other's behinds? Chemical communication explained (video)

2014-07-28

WASHINGTON, July 28, 2014 — Here at Reactions, we ask the tough questions to get to the bottom of the biggest scientific quandaries. In that spirit, this week's video explains why dogs sniff each other's butts. It's a somewhat silly question with a surprisingly complex answer. This behavior is just one of many interesting forms of chemical communication in the animal kingdom. Find out more at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PZlJ8XfwiNg.

Subscribe to the series at Reactions YouTube, and follow us on Twitter @ACSreactions to be the first to see our latest videos.

INFORMATION:

The ...

Refrigerator magnets

2014-07-28

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The magnets cluttering the face of your refrigerator may one day be used as cooling agents, according to a new theory formulated by MIT researchers.

The theory describes the motion of magnons — quasi-particles in magnets that are collective rotations of magnetic moments, or "spins." In addition to the magnetic moments, magnons also conduct heat; from their equations, the MIT researchers found that when exposed to a magnetic field gradient, magnons may be driven to move from one end of a magnet to another, carrying heat with them and producing a cooling ...