(Press-News.org) Toronto, Canada – Older adults who are tested at their optimal time of day (the morning), not only perform better on demanding cognitive tasks but also activate the same brain networks responsible for paying attention and suppressing distraction as younger adults, according to Canadian researchers.

The study, published online July 7th in the journal Psychology and Aging (ahead of print publication), has yielded some of the strongest evidence yet that there are noticeable differences in brain function across the day for older adults.

"Time of day really does matter when testing older adults. This age group is more focused and better able to ignore distraction in the morning than in the afternoon," said lead author John Anderson, a PhD candidate with the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest Health Sciences and University of Toronto, Department of Psychology.

"Their improved cognitive performance in the morning correlated with greater activation of the brain's attentional control regions – the rostral prefrontal and superior parietal cortex – similar to that of younger adults."

Asked how his team's findings may be useful to older adults in their daily activities, Anderson recommended that older adults try to schedule their most mentally-challenging tasks for the morning time. Those tasks could include doing taxes, taking a test (such as a driver's license renewal), seeing a doctor about a new condition, or cooking an unfamiliar recipe.

In the study, 16 younger adults (aged 19 – 30) and 16 older adults (aged 60-82) participated in a series of memory tests during the afternoon from 1 – 5 p.m. The tests involved studying and recalling a series of picture and word combinations flashed on a computer screen. Irrelevant words linked to certain pictures and irrelevant pictures linked to certain words also flashed on the screen as a distraction. During the testing, participants' brains were scanned with fMRI which allows researchers to detect with great precision which areas of the brain are activated.

Older adults were 10 percent more likely to pay attention to the distracting information than younger adults who were able to successfully focus and block this information. The fMRI data confirmed that older adults showed substantially less engagement of the attentional control areas of the brain compared to younger adults. Indeed, older adults tested in the afternoon were "idling" – showing activations in the default mode (a set of regions that come online primarily when a person is resting or thinking about nothing in particular) indicating that perhaps they were having great difficulty focusing. When a person is fully engaged with focusing, resting state activations are suppressed.

When 18 older adults were morning tested (8:30 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.) they performed noticeably better, according to two separate behavioural measures of inhibitory control. They attended to fewer distracting items than their peers tested at off-peak times of day, closing the age difference gap in performance with younger adults. Importantly, older adults tested in the morning activated the same brain areas young adults did to successfully ignore the distracting information. This suggests that 'when' older adults are tested is important for both how they perform and what brain activity one should expert to see.

"Our research is consistent with previous science reports showing that at a time of day that matches circadian arousal patterns, older adults are able to resist distraction," said Dr. Lynn Hasher, senior author on the paper and a leading authority in attention and inhibitory functioning in younger and older adults.

The Baycrest findings offer a cautionary flag to those who study cognitive function in older adults. "Since older adults tend to be morning-type people, ignoring time of day when testing them on some tasks may create an inaccurate picture of age differences in brain function," said Dr. Hasher, senior scientist at Baycrest's Rotman Research Institute and Professor of Psychology at University of Toronto.

INFORMATION:

The Baycrest study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Older adults have morning brains!

Study shows noticeable differences in brain function across the day

2014-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New hand-held device uses lasers, sound waves for deeper melanoma imaging

2014-08-06

WASHINGTON, Aug. 6, 2014—A new hand-held device that uses lasers and sound waves may change the way doctors treat and diagnose melanoma, according to a team of researchers from Washington University in St. Louis. The instrument, described in a paper published today in The Optical Society's (OSA) journal Optics Letters, is the first that can be used directly on a patient and accurately measure how deep a melanoma tumor extends into the skin, providing valuable information for treatment, diagnosis or prognosis.

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer type in the United ...

Trapped: Cell-invading piece of virus captured in lab by SLU scientists

2014-08-06

ST. LOUIS – In recent research published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Saint Louis University investigators report catching integrase, the part of retroviruses like HIV that is responsible for insertion of the viral DNA into human cell DNA, in the presence of a drug designed to thwart it.

This achievement sets the stage to use x-ray crystallography to develop complete images of HIV that include integrase, which in turn will help scientists develop new treatments for the illness.

Duane Grandgenett, Ph.D., professor at SLU's Institute of Molecular Virology ...

Transplanting neural progenitors to build a neuronal relay across the injured spinal cord

2014-08-06

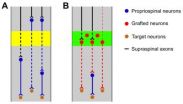

Cellular transplantation for repair of spinal cord injury is a promising therapeutic strategy that includes the use of a variety of neural and non-neural cells isolated or derived from embryonic and adult tissue as well as embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. In particular, transplants of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) have been shown to limit secondary injury and scar formation and create a permissive environment in the injured spinal cord through the provision of neurotrophic molecules and growth supporting matrices that promote growth of injured host ...

Relay strategies combined with axon regeneration: A promising approach to restore spinal cord injury

2014-08-06

For decades, numerous investigations have only focused on axon regeneration to restore function after traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI), as interrupted neuronal pathways have to be reconnected for sensorimotor and autonomic recovery to occur. Experimental approaches have ranged from drug delivery and cell transplantation to genetic manipulations. Certainly, it would be an extraordinary achievement for injured axons to regenerate over long distances, to form synapses with target neurons, and to result in dramatic functional improvement. Dr. Shaoping Hou from Drexel University ...

Exposure to inflammatory bowel disease drugs could increase leukemia risk

2014-08-06

Bethesda, MD (August 6, 2014) – Immunosuppressive drugs called thiopurines have been found to increase the risk of myeloid disorders, such as acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, a rare bone marrow disorder, seven-fold among inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. These data were reported in a new study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Thiopurines are an established treatment for IBD patients, used to reduce inflammation and provide symptom ...

Burrowing animals may have been key to stabilizing Earth's oxygen

2014-08-06

Evolution of the first burrowing animals may have played a major role in stabilizing the Earth's oxygen reservoir, according to a new study in Nature Geoscience.

Around 540 million years ago, the first burrowing animals evolved. When these worms began to mix up the ocean floor's sediments (a process known as bioturbation), their activity came to significantly influence the ocean's phosphorus cycle and as a result, the amount of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere.

"Our research is an attempt to place the spread of animal life in the context of wider biogeochemical cycles, ...

Skull shape risk factors could help in the welfare of toy dog breeds

2014-08-06

New research has identified two significant risk factors associated with painful neurological diseases in the skull shape of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS). The findings could help in tackling these conditions in toy dog breeds and could be used in breeding guidelines.

The study conducted by undergraduate student, Thomas Mitchell, from the University of Bristol's School of Veterinary Sciences, and supervised by Dr Clare Rusbridge, is published online in the journal Canine Genetics and Epidemiology.

Syringomyelia (SM) is a painful condition in dogs and is ...

Aggressive behaviour increases adolescent drinking, depression doesn't

2014-08-06

Adolescents who behave aggressively are more likely to drink alcohol and in larger quantities than their peers, according to a recent study completed in Finland. Depression and anxiety, on the other hand, were not linked to increased alcohol use. The study investigated the association between psychosocial problems and alcohol use among 4074 Finnish 13- to 18-year-old adolescents. The results were published in Journal of Adolescence.

The results indicate that smoking and attention problems also increase the probability of alcohol use. Furthermore, among girls, early menarche ...

A synopsis of the carabid beetle tribe Lachnophorini reveals remarkable 24 new species

2014-08-06

An extensive study by Smithsonian scientists presents a synopsis of the carabid beetle tribe Lachnophorini. The research contains a new genus and the remarkable 24 new species added to the tribe. The study was published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

Beetles from the family Carabidae, commonly known as ground beetles are a large, cosmopolitan group, with more than 40,000 species worldwide, Carabid beetles range in size from 0.6 mm to 90.2 mm and occur in nature in several fractal universes influencing life therein as predators, ectoparasitoids, seed eaters, and even ...

Study: arctic mammals can metabolize some pesticides, limits human exposure

2014-08-06

Fortunately, you are not always what you eat – at least in Canada's Arctic.

New research from the University of Guelph reveals that arctic mammals such as caribou can metabolize some current-use pesticides (CUPs) ingested in vegetation.

This limits exposures in animals that consume the caribou – including humans.

"This is good news for the wildlife and people of the Arctic who survive by hunting caribou and other animals," said Adam Morris, a PhD student in the School of Environmental Sciences and lead author of the study published recently in Environmental Toxicology ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Concrete sensor manufacturer Wavelogix receives $500,000 grant from National Science Foundation

California communities’ recovery time between wildfire smoke events is shrinking

Augmented reality job coaching boosts performance by 79% for people with disabilities

Medical debt associated with deferring dental, medical, and mental health care

AAI appoints Anand Balasubramani as Chief Scientific Programs Officer

Prior authorization may hinder access to lifesaving heart failure medications

Scholars propose transparency, credit and accountability as key principles in scientific authorship guidelines

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop DDINet for accurate and scalable drug-drug interaction prediction

IEEE researchers achieve 20x signal boost in cerebral blood flow monitoring with next-generation interferometric diffusing wave spectroscopy

IEEE researchers achieve low-power ultrashort mid-IR pulse compression

Deep-sea natural compound targets cancer cells through a dual mechanism

Antibiotics can affect the gut microbiome for several years

Study: Electrical stimulation can restore ability to move limbs, receive sensory feedback after spinal cord injury

Rice scientists unveil new tool to watch quantum behavior in action

Gene-based therapies poised for major upgrade thanks to Oregon State University research

Extreme heat has extreme effects r—but some like it hot

Blood marker for Alzheimer’s may also be useful in heart and kidney diseases

Climate extremes hinder early development in young birds

Climate policies: The swing voters that determine their fate

Building protection against infectious diseases with nanostructured vaccines

Oval orbit casts new light on black hole - neutron star mergers

Does online sports gambling affect substance use behaviors?

How do rapid socio-environmental transitions reshape cancer risk?

Do abortion bans affect birth rates and food-assistance costs?

Can artificial intelligence help reduce the carbon footprint of weather forecasting models?

Mangrove forests are short of breath

Low testosterone, high fructose: A recipe for liver disaster

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

[Press-News.org] Older adults have morning brains!Study shows noticeable differences in brain function across the day