(Press-News.org) ST. LOUIS – In recent research published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Saint Louis University investigators report catching integrase, the part of retroviruses like HIV that is responsible for insertion of the viral DNA into human cell DNA, in the presence of a drug designed to thwart it.

This achievement sets the stage to use x-ray crystallography to develop complete images of HIV that include integrase, which in turn will help scientists develop new treatments for the illness.

Duane Grandgenett, Ph.D., professor at SLU's Institute of Molecular Virology and senior author of the study, discovered integrase in 1978, little knowing the piece of virus would provide the basis for an entire class of drugs that now treats HIV.

"In 1974, we hadn't heard of HIV yet," Grandgenett said. "We did, however, study retroviruses, the class of viruses that includes HIV. Retroviruses spread by taking over your cell's DNA.

"And the way the virus does this is with integrase. It's responsible for inserting the genetic information of the virus, the DNA, into our chromosomes establishing the viral reservoir. Then, it uses our cells to replicate.

"Integrase is a key component that makes HIV pathogenic."

When a person is infected with HIV, there is an initial burst of virus production. This is when integrase inserts the virus DNA into many human cells, including CD4 T-immune cells, brain cells and other lymph cells. HIV is particularly devastating to the immune system's T-cells, which protect the body from infection.

"Most people do not die from virus replication but from secondary causes," Grandgenett said. "Their immune system collapses and opportunistic infections and cancer are what really kill the person."

Now, scientists have developed drugs that are very successful at managing HIV. Combinational drug therapy is particularly effective. The virus mutates so that it can quickly become resistant to a drug. But when three different drugs aim at three different targets, as in combination drug therapy, the probability of drug resistance is much smaller.

There is one catch, however. Patients must take the drugs every day. If they do not, the virus starts cycling again and within a few weeks the viral levels are back up.

Scientists continue to try to stay a step ahead of the virus, both to combat drug resistance and to develop better treatments.

To develop better drugs, scientists want to use a process called x-ray crystallography to develop a complete picture of how integrase inhibitors – the class of HIV drugs that target integrase-- interact with the virus.

"We're aiming to develop newer, better medicines," Grandgenett said. "We want to better understand how the integrase inhibitor drugs interact with integrase.

"So far, everybody has failed to produce HIV integrase-DNA images via high resolution x-ray crystallography," Grandgenett said. "No one has ever captured the mother load."

This is Grandgenett's goal.

"Now, we're going after full length integrase protein with DNA," Grandgenett said. "This is what I've wanted to do since 1978, even before HIV was identified."

To do this, Grandgenett and his team, including investigators Krishan Pandey, Ph.D., and Sibes Bera, Ph.D., needed to develop an integrase-DNA complex and then kinetically stabilize the complex in the presence of the drug.

Researchers used a surrogate virus to take a shortcut. Because integrase structures are similar in all retroviruses, Grandgenett tried his approach in Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), whose integrase is more readily manipulated than HIV integrase.

All current clinical integrase inhibitors work in the same way: They block integrase which prevents HIV from replicating. Specifically, they do this by stopping viral DNA strand transfer with STIs – strand transfer inhibitors.

Those inhibitors work by binding three components together: viral DNA; viral integrase; and the drug itself. Before this study, no one had been able to produce a synaptic complex (SC) in solution, the place where these three elements meet.

The researchers developed conditions where the HIV strand transfer inhibitors (STIs) trapped the SC of the surrogate RSV integrase. Grandgenett reports that this experiment is first time anyone has ever captured an integrase-DNA-inhibitor SC in solution.

"We've isolated it and now we want to do x-ray crystallography on it to get a better image of HIV integrase," Grandgenett said. "That's the next step. Hopefully, that crystal structure will better explain how integrase drugs and DNA interact at the nanometer level.

"This will help us to design new drugs. There will be a lot of uses for this information."

INFORMATION:

Established in 1836, Saint Louis University School of Medicine has the distinction of awarding the first medical degree west of the Mississippi River. The school educates physicians and biomedical scientists, conducts medical research, and provides health care on a local, national and international level. Research at the school seeks new cures and treatments in five key areas: cancer, liver disease, heart/lung disease, aging and brain disease, and infectious disease.

Trapped: Cell-invading piece of virus captured in lab by SLU scientists

Researchers aim to complete picture of HIV

2014-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

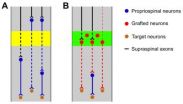

Transplanting neural progenitors to build a neuronal relay across the injured spinal cord

2014-08-06

Cellular transplantation for repair of spinal cord injury is a promising therapeutic strategy that includes the use of a variety of neural and non-neural cells isolated or derived from embryonic and adult tissue as well as embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. In particular, transplants of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) have been shown to limit secondary injury and scar formation and create a permissive environment in the injured spinal cord through the provision of neurotrophic molecules and growth supporting matrices that promote growth of injured host ...

Relay strategies combined with axon regeneration: A promising approach to restore spinal cord injury

2014-08-06

For decades, numerous investigations have only focused on axon regeneration to restore function after traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI), as interrupted neuronal pathways have to be reconnected for sensorimotor and autonomic recovery to occur. Experimental approaches have ranged from drug delivery and cell transplantation to genetic manipulations. Certainly, it would be an extraordinary achievement for injured axons to regenerate over long distances, to form synapses with target neurons, and to result in dramatic functional improvement. Dr. Shaoping Hou from Drexel University ...

Exposure to inflammatory bowel disease drugs could increase leukemia risk

2014-08-06

Bethesda, MD (August 6, 2014) – Immunosuppressive drugs called thiopurines have been found to increase the risk of myeloid disorders, such as acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, a rare bone marrow disorder, seven-fold among inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. These data were reported in a new study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Thiopurines are an established treatment for IBD patients, used to reduce inflammation and provide symptom ...

Burrowing animals may have been key to stabilizing Earth's oxygen

2014-08-06

Evolution of the first burrowing animals may have played a major role in stabilizing the Earth's oxygen reservoir, according to a new study in Nature Geoscience.

Around 540 million years ago, the first burrowing animals evolved. When these worms began to mix up the ocean floor's sediments (a process known as bioturbation), their activity came to significantly influence the ocean's phosphorus cycle and as a result, the amount of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere.

"Our research is an attempt to place the spread of animal life in the context of wider biogeochemical cycles, ...

Skull shape risk factors could help in the welfare of toy dog breeds

2014-08-06

New research has identified two significant risk factors associated with painful neurological diseases in the skull shape of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS). The findings could help in tackling these conditions in toy dog breeds and could be used in breeding guidelines.

The study conducted by undergraduate student, Thomas Mitchell, from the University of Bristol's School of Veterinary Sciences, and supervised by Dr Clare Rusbridge, is published online in the journal Canine Genetics and Epidemiology.

Syringomyelia (SM) is a painful condition in dogs and is ...

Aggressive behaviour increases adolescent drinking, depression doesn't

2014-08-06

Adolescents who behave aggressively are more likely to drink alcohol and in larger quantities than their peers, according to a recent study completed in Finland. Depression and anxiety, on the other hand, were not linked to increased alcohol use. The study investigated the association between psychosocial problems and alcohol use among 4074 Finnish 13- to 18-year-old adolescents. The results were published in Journal of Adolescence.

The results indicate that smoking and attention problems also increase the probability of alcohol use. Furthermore, among girls, early menarche ...

A synopsis of the carabid beetle tribe Lachnophorini reveals remarkable 24 new species

2014-08-06

An extensive study by Smithsonian scientists presents a synopsis of the carabid beetle tribe Lachnophorini. The research contains a new genus and the remarkable 24 new species added to the tribe. The study was published in the open access journal ZooKeys.

Beetles from the family Carabidae, commonly known as ground beetles are a large, cosmopolitan group, with more than 40,000 species worldwide, Carabid beetles range in size from 0.6 mm to 90.2 mm and occur in nature in several fractal universes influencing life therein as predators, ectoparasitoids, seed eaters, and even ...

Study: arctic mammals can metabolize some pesticides, limits human exposure

2014-08-06

Fortunately, you are not always what you eat – at least in Canada's Arctic.

New research from the University of Guelph reveals that arctic mammals such as caribou can metabolize some current-use pesticides (CUPs) ingested in vegetation.

This limits exposures in animals that consume the caribou – including humans.

"This is good news for the wildlife and people of the Arctic who survive by hunting caribou and other animals," said Adam Morris, a PhD student in the School of Environmental Sciences and lead author of the study published recently in Environmental Toxicology ...

New material structures bend like microscopic hair

2014-08-06

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT engineers have fabricated a new elastic material coated with microscopic, hairlike structures that tilt in response to a magnetic field. Depending on the field's orientation, the microhairs can tilt to form a path through which fluid can flow; the material can even direct water upward, against gravity.

Each microhair, made of nickel, is about 70 microns high and 25 microns wide — about one-fourth the diameter of a human hair. The researchers fabricated an array of the microhairs onto an elastic, transparent layer of silicone.

In experiments, the ...

Coping skills help women overcome the mental anguish of unwanted body evaluation and sexual advances

2014-08-06

Some young women simply have more resilience and better coping skills and can shrug off the effect of unwanted cat calls, demeaning looks and sexual advances. Women with low resilience struggle and could develop psychological problems when they internalize such behavior, because they think they are to blame. So say Dawn Szymanski and Chandra Feltman of the University of Tennessee in the US, in Springer's journal Sex Roles, after studying how female college students handle the sexually objectifying behavior of men.

According to the popular feminist Objectification Theory, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Trapped: Cell-invading piece of virus captured in lab by SLU scientistsResearchers aim to complete picture of HIV