(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA — Postmenopausal women who in the past four years had undertaken regular physical activity equivalent to at least four hours of walking per week had a lower risk for invasive breast cancer compared with women who exercised less during those four years, according to data published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"Twelve MET-h [metabolic equivalent task-hours] per week corresponds to walking four hours per week or cycling or engaging in other sports two hours per week and it is consistent with the World Cancer Research Fund recommendations of walking at least 30 minutes daily," said Agnès Fournier, PhD, a researcher in the Centre for Research in Epidemiology and Population Health at the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. "So, our study shows that it is not necessary to engage in vigorous or very frequent activities; even walking 30 minutes per day is beneficial."

Postmenopausal women who in the previous four years had undertaken 12 or more MET-h of physical activity each week had a 10 percent decreased risk of invasive breast cancer compared with women who were less active. Women who undertook this level of physical activity between five and nine years earlier but were less active in the four years prior to the final data collection did not have a decreased risk for invasive breast cancer.

"Physical activity is thought to decrease a woman's risk for breast cancer after menopause," said Fournier. "However, it was not clear how rapidly this association is observed after regular physical activity is begun or for how long it lasts after regular exercise stops.

"Our study answers these questions," Fournier continued. "We found that recreational physical activity, even of modest intensity, seemed to have a rapid impact on breast cancer risk. However, the decreased breast cancer risk we found associated with physical activity was attenuated when activity stopped. As a result, postmenopausal women who exercise should be encouraged to continue and those who do not exercise should consider starting because their risk of breast cancer may decrease rapidly."

Fournier and colleagues analyzed data obtained from biennial questionnaires completed by 59,308 postmenopausal women who were enrolled in E3N, the French component of the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. The mean duration of follow-up was 8.5 years, during which time, 2,155 of the women were diagnosed with a first primary invasive breast cancer.

The total amount of self-reported recreational physical activity was calculated in MET-h per week. The breast cancer risk-reducing effects of 12 or more MET-h per week of recreational physical activity were independent of body mass index, weight gain, waist circumference, and the level of activity from five to nine years earlier.

INFORMATION:

This study was supported by funds from Institut National du Cancer, the Fondation de France, and the Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique. The E3N cohort is financially supported by the Institut National du Cancer, the Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale, the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave Roussy, and the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. Fournier declares no conflicts of interest.

Follow us: Cancer Research Catalyst http://blog.aacr.org; Twitter @AACR; and Facebook http://www.facebook.com/aacr.org

To interview Agnès Fournier, please contact her at agnes.fournier@gustaveroussy.fr or +33-1-42-11-51-63. For all other inquiries, please contact Jeremy Moore at jeremy.moore@aacr.org or 215-446-7109. Visit our newsroom.

About the American Association for Cancer Research

Founded in 1907, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) is the world's oldest and largest professional organization dedicated to advancing cancer research and its mission to prevent and cure cancer. AACR membership includes more than 34,000 laboratory, translational, and clinical researchers; population scientists; other health care professionals; and cancer advocates residing in more than 90 countries. The AACR marshals the full spectrum of expertise of the cancer community to accelerate progress in the prevention, biology, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer by annually convening more than 20 conferences and educational workshops, the largest of which is the AACR Annual Meeting with more than 18,000 attendees. In addition, the AACR publishes eight peer-reviewed scientific journals and a magazine for cancer survivors, patients, and their caregivers. The AACR funds meritorious research directly as well as in cooperation with numerous cancer organizations. As the Scientific Partner of Stand Up To Cancer, the AACR provides expert peer review, grants administration, and scientific oversight of team science and individual grants in cancer research that have the potential for near-term patient benefit. The AACR actively communicates with legislators and policymakers about the value of cancer research and related biomedical science in saving lives from cancer. For more information about the AACR, visit http://www.AACR.org.

Postmenopausal breast cancer risk decreases rapidly after starting reg. physical activity

Benefits quickly disappear if regular physical activity stops

2014-08-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Breech babies have higher risk of death from vaginal delivery compared to C-section

2014-08-11

While a rise in cesarean section (C-section) delivery rates due to breech presentation has improved neonatal outcome, 40% of term breech deliveries in the Netherlands are planned vaginal deliveries. According to a new Dutch study that is published today in Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, a journal of the Nordic Federation of Societies of Obstetrics and Gynecology, there is a 10-fold increase in fetal mortality in vaginal delivery for breech presentation compared to elective C-section.

Up to 4% of deliveries are breech births—when the baby is delivered buttocks ...

Spectacular 3-D sketching system revolutionizes design interaction and collaboration

2014-08-11

Collaborative three-dimensional sketching is now possible thanks to a system known as Hyve-3D that University of Montreal researchers are presenting today at the SIGGRAPH 2014 conference in Vancouver. "Hyve-3D is a new interface for 3D content creation via embodied and collaborative 3D sketching," explained lead researcher Professor Tomás Dorta, of the university's School of Design. "The system is a full scale immersive 3D environment. Users create drawings on hand-held tables. They can then use the tablets to manipulate the sketches to create a 3D design within the space". ...

Discovery of new form of dystrophin protein could lead to therapy for some DMD patients

2014-08-10

Scientists have discovered a new form of dystrophin, a protein critical to normal muscle function, and identified the genetic mechanism responsible for its production. Studies of the new protein isoform, published online Aug. 10 in Nature Medicine and led by a team in The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital, suggest it may offer a novel therapeutic approach for some patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a debilitating neuromuscular condition that usually leaves patients unable to walk on their own by age 12.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or DMD, ...

Scientists unlock key to blood vessel formation

2014-08-10

Scientists from the University of Leeds have discovered a gene that plays a vital role in blood vessel formation, research which adds to our knowledge of how early life develops.

The discovery could also lead to greater understanding of how to treat cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Professor David Beech, of the School of Medicine at the University of Leeds, who led the research, said: "Blood vessel networks are not already pre-constructed but emerge rather like a river system. Vessels do not develop until the blood is already flowing and they are created in response ...

Newly discovered heart molecule could lead to effective treatment for heart failure

2014-08-10

INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers have discovered a previously unknown cardiac molecule that could provide a key to treating, and preventing, heart failure.

The newly discovered molecule provides the heart with a tool to block a protein that orchestrates genetic disruptions when the heart is subjected to stress, such as high blood pressure.

When the research team, led by Ching-Pin Chang, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of medicine at the Indiana University School of Medicine, restored levels of the newly discovered molecule in mice experiencing heart failure, the progression ...

Bioengineers: Matrix stiffness is an essential tool in stem cell differentiation

2014-08-10

Bioengineers at the University of California, San Diego have proven that when it comes to guiding stem cells into a specific cell type, the stiffness of the extracellular matrix used to culture them really does matter. When placed in a dish of a very stiff material, or hydrogel, most stem cells become bone-like cells. By comparison, soft materials tend to steer stem cells into soft tissues such as neurons and fat cells. The research team, led by bioengineering professor Adam Engler, also found that a protein binding the stem cell to the hydrogel is not a factor in the differentiation ...

Pairing old technologies with new for next generation electronic devices

2014-08-10

UCL scientists have discovered a new method to efficiently generate and control currents based on the magnetic nature of electrons in semi-conducting materials, offering a radical way to develop a new generation of electronic devices.

One promising approach to developing new technologies is to exploit the electron's tiny magnetic moment, or 'spin'. Electrons have two properties – charge and spin – and although current technologies use charge, it is thought that spin-based technologies have the potential to outperform the 'charge'-based technology of semiconductors for ...

Physicists create water tractor beam

2014-08-10

VIDEO:

Physicists at the Australian National University have created a tractor beam in water. Using a simple wave generator they can create water currents which could be used to confine oil...

Click here for more information.

Physicists at The Australian National University (ANU) have created a tractor beam on water, providing a radical new technique that could confine oil spills, manipulate floating objects or explain rips at the beach.

The group, led by Professor Michael ...

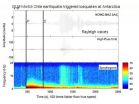

2010 Chilean earthquake causes icequakes in Antarctica

2014-08-10

VIDEO:

High-frequency icequakes are shown at station HOWD in Antarctica during the distant waves of the 2010 magnitude 8.8 Chile earthquake. The triggered icequakes are indicated by the narrow vertical bands...

Click here for more information.

Seismic events aren't rare occurrences on Antarctica, where sections of the frozen desert can experience hundreds of micro-earthquakes an hour due to ice deformation. Some scientists call them icequakes. But in March of 2010, the ice sheets ...

Target identified for rare inherited neurological disease in men

2014-08-10

Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified the mechanism by which a rare, inherited neurodegenerative disease causes often crippling muscle weakness in men, in addition to reduced fertility.

The study, published August 10 in the journal Nature Neuroscience, shows that a gene mutation long recognized as a key to the development of Kennedy's disease impairs the body's ability to degrade, remove and recycle clumps of "trash" proteins that may otherwise build up on neurons, progressively impairing their ability to control muscle ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

[Press-News.org] Postmenopausal breast cancer risk decreases rapidly after starting reg. physical activityBenefits quickly disappear if regular physical activity stops