(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Dangerous brain tumors hijack the brain's existing blood supply throughout their progression, by growing only within narrow potential spaces between and along the brain's thousands of small blood vessels, new research shows for the first time.

The findings contradict the concept that brain tumors need to grow their own blood vessels to keep themselves growing – and help explain why drugs that aim to stop growth of the new blood vessels have failed in clinical trials to extend the lives of patients with the worst brain tumors.

In fact, trying to block the growth of new blood vessels in the brain actually spurs malignant tumors called gliomas to grow faster and further, the research shows. On the hopeful side, the research suggests a new avenue for finding better drugs.

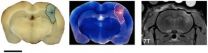

The discoveries come from a University of Michigan Medical School team studying tumors in rodents and humans, and advanced computer models, in collaboration with colleagues from Arizona State University. Published online in the journal Neoplasia, they'll be featured as the journal's cover article later this month.

Build or Borrow?

The vessels that the researchers studied feed the brain's constant need for energy and communication with the rest of the body. They have a special vessel wall structure that protects the brain from infection or other blood-borne dangers.

The new findings show that tumor cells grow exclusively within the spaces around the vessels, close enough to draw their own energy and fuel their growth in the same way normal brain tissue does. Instead of spawning their own offshoots of these vessels as the tumor cells divide, they simply crowd out the normal cells in the immediate area and continue to fill the spaces between neighboring vessels.

This continued "autovascular" growth, as the researchers call it, was detected from the very beginning to the final stages of tumor progression. It runs directly counter to the theory of neoangiogenesis, or new blood vessel formation, that has driven the use of certain drugs to treat brain tumors such as glioblastoma multiforme and other cancers.

Last year, two clinical trials showed that glioblastoma patients taking an anti-angiogenic drug as part of treatment didn't survive any longer, and in some cases suffered more side effects than patients who didn't get the drug. Patients whose glioblastoma has returned after treatment also use the drug to reduce swelling.

The researchers caution that it's far too soon for patients to make medical decisions based on their findings.

But they note that further research on how new therapies will directly affect the tumor cells growing along blood vessels is already under way.

"The key question has been to determine how tumor-generating cells grow to form the macroscopic tumor mass that eventually kills the patients," says Pedro Lowenstein, M.D., Ph.D., the senior author of the new paper and a U-M Neuroscientist and Professor in the Departments of Neurosurgery and Cell & Developmental Biology. "We have shown that because of the very high density of endogenous vessels in the brain and central nervous system, the cells grow along those pre-existing vessels and eventually divide to fill the space between them, where the distance between any two vessels is very small."

"This iterative growth along vessels and into the space between means the tumor does not grow like a balloon requiring new vessels to grow into its expanding mass to rescue it," he continues, "but rather as an accumulation of local small masses which then coalesce into a large tumor."

Lowenstein notes that the angiogenesis theory of all tumor growth proposes that tumors more than one cubic millimeter in size need to attract their own blood vessels to survive. The theory emerged after research on non-vascularized tissue. But in the brain, a very large density of blood vessels already exists within that volume of brain tissue. And few tumor cells are sufficient to fill the space in between any two vessels.

The researchers confirmed this by examining tissue from mice and humans through special microscopes – and modeling their growth predictions with powerful computers. They also saw that tumors caused the cells of the blood vessels' walls to spread apart – allowing fluid to leak out. This "leakiness" results in the edema, or fluid-based swelling, often associated with brain tumors.

In the new study, the research team did show that, as expected, the anti-angiogenesis drug bevacizumab did stabilize the walls of the tiny vessels, reducing edema. This echoes the experience of human patients who use the drug for recurrent gliobastoma – many experience a reduction in cognitive symptoms and increased quality of life because less fluid builds up in their brains.

But almost perversely, the same drug designed to stop tumors may actually make it easier for them to grow. In the newly published research, mice with brain tumors treated with the drug died at the same time as mice that didn't receive the drug for their tumors.

By tightening up the leaky vessel walls, the drug may make it easier for tumor cells to continue the autovascularization process, the researchers suggest. Lowenstein's research partner Maria Castro, Ph.D., a Professor of Neurosurgery and Cell and Developmental Biology, says "it's as if the tumor's growth along the "road" of a blood vessel had resulted in many potholes to form on the road's surface. But when the anti-angiogenesis drug is given, essentially patching the potholes, the tumor cells get a smoother road to grow along. It may even give them a highway across the divide between the brain's halves."

Armed with this new understanding, the research team has shifted its focus to finding ways to attack tumors from within the vessels they grow along. Working with U-M Chemistry Department and College of Pharmacy researchers, they're looking for ways to deliver molecular nano-sized drugs intravenously in the immediate area of the tumor. They're also studying in more detail how the tumor cell growth changes the structure of blood vessel walls and the surrounding tissue.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Lowenstein and Castro, the research team included graduate student and first author Gregory J. Baker, laboratory team members Viveka Nand Yadav, U-M pediatric haematology oncologist Carl Koschmann, Anda-Alexandra Calinescu and Yohei Mineharu; U-M neurosurgeon Daniel Orringer, M.D., U-M neuropathologist Sandra Camelo-Piragua, M.D., and colleagues from University of California, Los Angeles, Arizona State University, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

The research was funded by the National institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NS054193, NS061107, NS082311, NS052465, NS057711 and NS074387). Additional support came from the U-M Department of Neurosurgery including a gift from Phil Jenkins to fund advanced microscopy. Reference: Neoplasia, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2014.06.003,Vol. 16, No. 7, 2014

Hijacking the brain's blood supply: tumor discovery could aid treatment

Gliomas don't grow their own blood vessels, Unversity of Michigan-led team finds

2014-08-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Lead released from African cookware contaminates food

2014-08-12

San Francisco and Yaoundé – Lead levels in foods prepared in aluminum pots from Cameroon exceed U.S. guidelines for lead consumption according to a new study published this month. A typical serving contains almost 200 times more lead than California's Maximum Allowable Dose Level (MADL) of 0.5 micrograms per day.

Researchers at Ashland University and Occupational Knowledge International tested 29 samples of aluminum cookware made in Cameroon and found almost all had considerable lead content. This cookware is common throughout Africa and Asia and is made from recycled ...

Changes in motor function in the unaffected hand of stroke patients should not be ignored

2014-08-12

With effective rehabilitation, stroke patients can partially regain their motor control and continue their activities of daily living. Motor function changes in the unaffected hand of stroke patients with hemiplegia. However, these changes are often ignored by clinicians owing to the extent of motor disability of the affected hand. Research group at Shanghai University of Sport, China led by Prof. Zhusheng Yu based on finger tapping frequency and Lind-mark hand function score have found that the motor function of unaffected hands in stroke patients was poorer than that ...

Neuroprotective effect of tongxinluo: a PET imaging study in small animals

2014-08-12

Tongxinluo has been widely used in China for the treatment of acute stroke and for neuroprotection. Research group at Encephalopathy Center, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China intragastrically administered Tongxinluo superfine powder suspension or its vehicle to rats for 5 successive days before middle cerebral artery occlusion. There are many advantages of using small animal PET for drug research. First, the results of the study in vitro cannot be directly applied to human studies, while small animal PET imaging methods and results can ...

ASU-Mayo researchers use calcium isotope analysis to predict myeloma progression

2014-08-12

TEMPE, Ariz. – A team of researchers from Arizona State University and Mayo Clinic is showing how a staple of Earth science research can be used in biomedical settings to predict the course of disease.

The researchers tested a new approach to detecting bone loss in cancer patients by using calcium isotope analysis to predict whether myeloma patients are at risk for developing bone lesions, a hallmark of the disease.

They believe they have a promising technique that could be used to chart the progression of multiple myeloma, a lethal disease that eventually impacts ...

Neutrino detectors could help curb nuclear weapons activity

2014-08-12

Physicists at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland and even in the fictional world of CBS' "The Big Bang Theory" look to subatomic particles called neutrinos to answer the big questions about the universe.

Now, a group of scientists led by a physics professor with the College of Science at Virginia Tech are asking whether the neutrino could provide the world with clues about nuclear proliferation in Iran and other political hotspots.

Neutrinos are produced by the decay of radioactive elements, and nuclear reactors produce large amounts of neutrinos that cannot ...

Focal blood-brain-barrier disruption with high-frequency pulsed electric fields

2014-08-12

A team of researchers from the Virginia Tech-Wake Forest University School of Biomedical Engineering and Sciences have developed a new way of using electricity to open the blood-brain-barrier (BBB). The Vascular Enabled Integrated Nanosecond pulse (VEIN pulse) procedure consists of inserting minimally invasive needle electrodes into the diseased tissue and applying multiple bursts of nanosecond pulses with alternating polarity. It is thought that the bursts disrupt tight junction proteins responsible for maintaining the integrity of the BBB without causing damage to the ...

A highly sensitive microsphere-based assay for early detection of Type I diabetes

2014-08-12

A team of researchers from the Center for Engineering in Medicine at the Massachusetts General Hospital have developed a novel fluorescence-based assay for sensitive detection of antibodies within microliter volume serum samples. This new assay is at least 50 times more sensitive than the traditional radioimmunoassay (RIA), which is the gold standard currently used in the clinic. This new technology is particularly attractive for immunological assays as it allows: 1) use of very small volumes of sample reagents (5 ¦ÌL), and 2) use of traditional analytical systems such ...

Biomarker could reveal why some develop post-traumatic stress disorder

2014-08-12

(NEW YORK – August 11) Blood expression levels of genes targeted by the stress hormones called glucocorticoids could be a physical measure, or biomarker, of risk for developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), according to a study conducted in rats by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and published August 11 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). That also makes the steroid hormones' receptor, the glucocorticoid receptor, a potential target for new drugs.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is triggered by a terrifying ...

Robotic-assisted imaging: from trans-Atlantic evaluation to help in daily practice

2014-08-12

While in Germany, Partho P. Sengupta, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai used a computer to perform a robot-assisted trans-Atlantic ultrasound examination on a person in Boston. In another study Kurt Boman, MD, of Umeå University in Sweden in collaboration with Mount Sinai, showed how a cardiologist's video e-consultation, coupled with a remote robot-assisted echocardiogram test, dramatically reduces the waiting time for a diagnosis faced by heart failure patients who live in a rural communities far from the hospital from nearly four months to less than one ...

The Maldives and the whale shark: The world's biggest fish adds value to paradise

2014-08-12

They are the largest fish in the world but the impact of this majestic and charismatic animal on the economy of the island nation of the Maldives was largely unknown. A new study by scientists of the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme (MWSRP) reveals that a small group of whale sharks in a single Maldivian Atoll accounts for nearly 3% of the global shark ecotourism and nearly half that of the Maldives'.

"The Republic of Maldives hosts one of few known year round aggregation sites for whale sharks", said James Hancock co-author and a director of MWSRP. "We have seen ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Hijacking the brain's blood supply: tumor discovery could aid treatmentGliomas don't grow their own blood vessels, Unversity of Michigan-led team finds