(Press-News.org) When investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine applied light-driven stimulation to nerve cells in the brains of mice that had suffered strokes several days earlier, the mice showed significantly greater recovery in motor ability than mice that had experienced strokes but whose brains weren't stimulated.

These findings, which will be published online Aug. 18 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help identify important brain circuits involved in stroke recovery and usher in new clinical therapies for stroke, including the placement of electrical brain-stimulating devices similar to those used for treating Parkinson's disease, chronic pain and epilepsy. The findings also highlight the neuroscientific strides made possible by a powerful research technique known as optogenetics.

Stroke, with 15 million new victims per year worldwide, is the planet's second-largest cause of death, according to Gary Steinberg, MD, PhD, professor and chair of neurosurgery and the study's senior author. In the United States, stroke is the largest single cause of neurologic disability, accounting for about 800,000 new cases each year — more than one per minute — and exacting an annual tab of about $75 billion in medical costs and lost productivity.

The only approved drug for stroke in the United States is an injectable medication called tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA. If infused within a few hours of the stroke, tPA can limit the extent of stroke damage. But no more than 5 percent of patients actually benefit from it, largely because by the time they arrive at a medical center the damage is already done. No pharmacological therapy has been shown to enhance recovery from stroke from that point on.

But in this study — the first to use a light-driven stimulation technology called optogenetics to enhance stroke recovery in mice — the stimulations promoted recovery even when initiated five days after stroke occurred.

"In this study, we found that direct stimulation of a particular set of nerve cells in the brain — nerve cells in the motor cortex — was able to substantially enhance recovery," said Steinberg, the Bernard and Ronni Lacroute-William Randolph Hearst Professor in Neurosurgery and Neurosciences.

About seven of every eight strokes are ischemic: They occur when a blood clot cuts off oxygen flow to one or another part of the brain, destroying tissue and leaving weakness, paralysis and sensory, cognitive and speech deficits in its wake. While some degree of recovery is possible — this varies greatly among patients depending on many factors, notably age — it's seldom complete, and typically grinds to a halt by three months after the stroke has occurred.

Animal studies have indicated that electrical stimulation of the brain can improve recovery from stroke. However, "existing brain-stimulation techniques activate all cell types in the stimulation area, which not only makes it difficult to study but can cause unwanted side effects," said the study's lead author, Michelle Cheng, PhD, a research associate in Steinberg's lab.

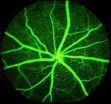

For the new study, the Stanford investigators deployed optogenetics, a technology pioneered by co-author Karl Deisseroth, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and of bioengineering. Optogenetics involves expressing a light-sensitive protein in specifically targeted brain cells. Upon exposure to light of the right wavelength, this light-sensitive protein is activated and causes the cell to fire.

Steinberg's team selectively expressed this protein in the brain's primary motor cortex, which is involved in regulating motor functions. Nerve cells within this cortical layer send outputs to many other brain regions, including its counterpart in the brain's opposite hemisphere. Using an optical fiber implanted in that region, the researchers were able to stimulate the primary motor cortex near where the stroke had occurred, and then monitor biochemical changes and blood flow there as well as in other brain areas with which this region was in communication. "We wanted to find out whether activating these nerve cells alone can contribute to recovery," Steinberg said.

By several behavioral, blood flow and biochemical measures, the answer two weeks later was a strong yes. On one test of motor coordination, balance and muscular strength, the mice had to walk the length of a horizontal beam rotating on its axis, like a rotisserie spit. Stroke-impaired mice whose primary motor cortex was optogenetically stimulated did significantly better in how far they could walk along the beam without falling off and in the speed of their transit, compared with their unstimulated counterparts.

The same treatment, applied to mice that had not suffered a stroke but whose brains had been similarly genetically altered and then stimulated just as stroke-affected mice's brains were, had no effect on either the distance they travelled along the rotating beam before falling off or how fast they walked. This suggests it was stimulation-induced repair of stroke damage, not the stimulation itself, yielding the improved motor ability.

Stroke-affected mice whose brains were optogenetically stimulated also regained substantially more of their lost weight than unstimulated, stroke-affected mice. Furthermore, stimulated post-stroke mice showed enhanced blood flow in their brain compared with unstimulated post-stroke mice.

In addition, substances called growth factors, produced naturally in the brain, were more abundant in key regions on both sides of the brain in optogenetically stimulated, stroke-affected mice than in their unstimulated counterparts. Likewise, certain brain regions of these optogenetically stimulated, post-stroke mice showed increased levels of proteins associated with heightened ability of nerve cells to alter their structural features in response to experience — for example, practice and learning. (Optogenetic stimulation of the brains of non-stroke mice produced no such effects.)

Steinberg said his lab is following up to determine whether the improvement is sustained in the long term. "We're also looking to see if optogenetically stimulating other brain regions after a stroke might be equally or more effective," he said. "The goal is to identify the precise circuits that would be most amenable to interventions in the human brain, post-stroke, so that we can take this approach into clinical trials."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grant 1R21NS082894), Russell and Elizabeth Siegelman, and Bernard and Ronni Lacroute. Other Stanford co-authors of the study are research assistant Eric Wang; research assistant Guohua Sun, MD, PhD; postdoctoral scholar Ahmet Arac, MD; research associate Alex Lee, PhD; medical student Lief Fenno, PhD; and undergraduate students Wyatt Woodson and Stephanie Wang.

Information about Stanford's Department of Neurosurgery, which also supported the work, is available at http://neurosurgery.stanford.edu.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Print media contact: Bruce Goldman at (650) 725-2106 (goldmanb@stanford.edu)

Broadcast media contact: M.A. Malone at (650) 723-6912 (mamalone@stanford.edu)

Targeted brain stimulation aids stroke recovery in mice, Stanford scientists find

2014-08-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fighting unfairness

2014-08-18

Just about every parent is familiar with the signs: the crying, the stomping feet and pouting lips, all of which are usually followed by a collapse to the floor and a wailed insistence that, "It's not fair!"

While most people – including many parents – see such tantrums merely as part of growing up, a new study conducted by Harvard scientists suggests that, even at a relatively young age, children have advanced ideas about fairness, and are willing to pay a personal price to intervene in what they believe are unfair situations, even when they have not been personally ...

Bacterial nanowires: Not what we thought they were

2014-08-18

For the past 10 years, scientists have been fascinated by a type of "electric bacteria" that shoots out long tendrils like electric wires, using them to power themselves and transfer electricity to a variety of solid surfaces.

Today, a team led by scientists at USC has turned the study of these bacterial nanowires on its head, discovering that the key features in question are not pili, as previously believed, but rather are extensions of the bacteria's outer membrane equipped with proteins that transfer electrons, called "cytochromes."

Scientists had long suspected ...

WSU researchers find crucial step in DNA repair

2014-08-18

PULLMAN, Wash.—Scientists at Washington State University have identified a crucial step in DNA repair that could lead to targeted gene therapy for hereditary diseases such as "children of the moon" and a common form of colon cancer.

Such disorders are caused by faulty DNA repair systems that increase the risk for cancer and other conditions.

The findings are published in this week's Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Regents Professor Michael Smerdon and post-doctoral ...

Worm virus details come to light

2014-08-18

HOUSTON – (Aug. 18, 2014) – Rice University scientists have won a race to find the crystal structure of the first virus known to infect the most abundant animal on Earth.

The Rice labs of structural biologist Yizhi Jane Tao and geneticist Weiwei Zhong, with help from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and Washington University, analyzed the Orsay virus that naturally infects a certain type of nematode, the worms that make up 80 percent of the living animal population.

The research reported today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences will help ...

Innate lymphoid cells elicit T cell responses

2014-08-18

In case of an inflammation the body releases substances that increase the immune defense. During chronic inflammation, this immune response gets out of control and can induce organ damage. A research group from the Department of Biomedicine at the University and the University Children's Hospital of Basel now discovered that innate lymphoid cells become activated and induce specific T and B cell responses during inflammation. These lymphoid cells are thus an important target for the treatment of infection and chronic inflammation. The study was recently published in the ...

Aspirin, take 2

2014-08-18

Hugely popular non-steroidal anti-inflammation drugs like aspirin, naproxen (marketed as Aleve) and ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) all work by inhibiting or killing an enzyme called cyclooxygenase – a key catalyst in production of hormone-like lipid compounds called prostaglandins that are linked to a variety of ailments, from headaches and arthritis to menstrual cramps and wound sepsis.

In a new paper, published this week in the online early edition of PNAS, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine conclude that aspirin has a second effect: ...

Pygmy phenotype developed many times, adaptive to rainforest

2014-08-18

The small body size associated with the pygmy phenotype is probably a selective adaptation for rainforest hunter-gatherers, according to an international team of researchers, but all African pygmy phenotypes do not have the same genetic underpinning, suggesting a more recent adaptation than previously thought.

"I'm interested in how rainforest hunter-gatherers have adapted to their very challenging environments," said George H. Perry, assistant professor of anthropology and biology, Penn State. "Tropical rainforests are difficult for humans to live in. It is extremely ...

Bionic liquids from lignin

2014-08-18

While the powerful solvents known as ionic liquids show great promise for liberating fermentable sugars from lignocellulose and improving the economics of advanced biofuels, an even more promising candidate is on the horizon – bionic liquids.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) have developed "bionic liquids" from lignin and hemicellulose, two by-products of biofuel production from biorefineries. JBEI is a multi-institutional partnership led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) that was established by the ...

Proteins critical to wound healing identified

2014-08-18

Mice missing two important proteins of the vascular system develop normally and appear healthy in adulthood, as long as they don't become injured. If they do, their wounds don't heal properly, a new study shows.

The research, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, may have implications for treating diseases involving abnormal blood vessel growth, such as the impaired wound healing often seen in diabetes and the loss of vision caused by macular degeneration.

The study appears Aug. 18 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) online ...

Climate change will threaten fish by drying out Southwest US streams, study predicts

2014-08-18

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Fish species native to a major Arizona watershed may lose access to important segments of their habitat by 2050 as surface water flow is reduced by the effects of climate warming, new research suggests.

Most of these fish species, found in the Verde River Basin, are already threatened or endangered. Their survival relies on easy access to various resources throughout the river and its tributary streams. The species include the speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus), roundtail chub (Gila robusta) and Sonora sucker (Catostomus insignis).

A key component ...