(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Penn and NIH researchers have demonstrated a never-before characterized type of cell movement. In this video, a cell's vimentin cytoskeleton (green) pulls the nucleus (red) forward to generate a high-pressure...

Click here for more information.

For decades, researchers have used petri dishes to study cell movement. These classic tissue culture tools, however, only permit two-dimensional movement, very different from the three-dimensional movements that cells make in a human body.

In a new study from the University of Pennsylvania and National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, scientists used an innovative technique to study how cells move in a three-dimensional matrix, similar to the structure of certain tissues, such as the skin. They discovered an entirely new type of cell movement whereby the nucleus helps propel cells through the matrix like a piston in an engine, generating pressure that thrusts the cell's plasma membrane forward.

"Our work elucidated a highly intriguing question: how cells move when they are in the complex and physiologically relevant environment of a 3-D extracellular matrix," said Hyun (Michel) Koo, a professor in the Department of Orthodontics at Penn's School of Dental Medicine. "We discovered that the nucleus can act as a piston that physically compartmentalizes the cell cytoplasm and increases the hydrostatic pressure driving the cell motility within a 3-D matrix."

Koo worked with lead author Ryan Petrie and senior author Kenneth Yamada, both of the National Institutes of Health's NIDCR, on the study, which is published this week in Science.

"We think it's a very important normal physiological mechanism of cell movement that has not been characterized previously," Petrie said.

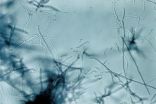

The team studied fibroblasts, the most common type of cell found in connective tissue. Fibroblasts themselves produce proteins including collagen and fibronectin that connect in a complex matrix that is found in the skin, the intestines and other tissues in the body.

The researchers used this fibroblast-created matrix to test how cells migrate through a three-dimensional structure. The matrix is crosslinked, meaning its fibers are resistant to bending and flexing as the cells move through.

Studies of fibroblasts on two-dimensional surfaces indicated that the most typical form of movement involved protrusions called lamellipodia, created by the polymerization of the protein actin into fibers that push the cell membrane forward. In 2012, however, Petrie and Yamada showed that when fibroblasts migrate they can switch to a different movement strategy when placed in a three-dimensional matrix, using blunt protrusions called lobopodia.

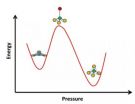

What the researchers did not know was how these lobopodia were formed. Suspecting they might be generated from increased intracellular pressure, the team used sophisticated microelectrodes to measure the hydrostatic pressure of the fluid inside the cell. They found that the pressure was significantly higher in cells moving in a three-dimensional extracellular matrix compared to cells moving along a two-dimensional surface or in a three-dimensional matrix that wasn't cross linked like the fibroblast-derived matrix.

To drill down further and see how the pressure was distributed within the cell moving in a three-dimensional matrix, they measured pressure from in front of and behind the nucleus. Cells moving using lobopodia have elevated pressure in front of the nucleus but not behind it, generating energy to propel the cell forward. Using live-cell confocal microscopy, they observed that the nucleus could be pulled forward, away from the rear of the cell, with the nucleus dividing the cell into low-pressure and high-pressure compartments.

"When a cell is in the matrix, the nucleus tends to be at the back of the cell, and the cell body is very tubular in shape," Petrie said. "It really looked like a piston."

They found that the nucleus is actually pulled forward by the actin filaments that connect the nucleus to the front of the cell. This movement "pressurizes" the cell. The scientists were also able to identify the protein components responsible for moving the nuclear piston, including actomyosin, vimentin and nesprin.

"The pressure itself is what pushes the plasma membrane," Petrie said.

Because this only happened to cells moving in the three-dimensional cell-created matrix and not cells moving in other substrates, the researchers note that the cells must be sensing their physical environment to determine what type of movement to use.

This type of cell migration might be common in other tissues of the body, the researchers noted. When they took chondrocytes from knee cartilage and myofibroblasts from intestinal tissue and placed them in the matrix, those cells used the same type of lobopodia-driven motion.

The discovery could have implications for understanding diseases such as cancer as well, because cancerous cells tend to move in distinct ways from normal cells.

"It might give us leverage to find out what is unique about cancer cells so we can target them therapeutically and not affect normal cells," Petrie said.

Importantly, these findings could have broader relevance to other biological systems where living cells are enmeshed within and surrounded by an extracellular matrix, such as in biofilms, which are associated with many human infectious diseases.

"This work illustrates how the physical structure of the matrix can influence cellular properties to govern biological function," Koo said. "We are now applying these fascinating principles to further understand how biofilm matrix modulates bacterial virulence to cause oral diseases, such as dental caries."

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Penn-NIH team discover new type of cell movement

2014-08-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How the zebrafish gets its stripes

2014-08-28

This news release is available in German. The zebrafish, a small fresh water fish, owes its name to a striking pattern of blue stripes alternating with golden stripes. Three major pigment cell types, black cells, reflective silvery cells, and yellow cells emerge during growth in the skin of the tiny juvenile fish and arrange as a multilayered mosaic to compose the characteristic colour pattern.

While it was known that all three cell types have to interact to form proper stripes, the embryonic origin of the pigment cells that develop the stripes of the adult fish has ...

Watching the structure of glass under pressure

2014-08-28

Glass has many applications that call for different properties, such as resistance to thermal shock or to chemically harsh environments. Glassmakers commonly use additives such as boron oxide to tweak these properties by changing the atomic structure of glass. Now researchers at the University of California, Davis, have for the first time captured atoms in borosilicate glass flipping from one structure to another as it is placed under high pressure.

The findings may have implications for understanding how glasses and similar "amorphous" materials respond at the atomic ...

Bradley Hospital collaborative study identifies genetic change in autism-related gene

2014-08-28

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – A new study from Bradley Hospital has identified a genetic change in a recently identified autism-associated gene, which may provide further insight into the causes of autism. The study, now published online in the Journal of Medical Genetics, presents findings that likely represent a definitive clinical marker for some patients' developmental disabilities.

Using whole-exome sequencing – a method that examines the parts of genes that regulate protein, called exons - the team identified a genetic change in a newly recognized autism-associated gene, Activity-Dependent ...

Yale study identifies possible bacterial drivers of IBD

2014-08-28

Yale University researchers have identified a handful of bacterial culprits that may drive inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, using patients' own intestinal immune responses as a guide.

The findings are published Aug. 28 in the journal Cell.

Trillions of bacteria exist within the human intestinal microbiota, which plays a critical role in the development and progression of IBD. Yet it's thought that only a small number of bacterial species affect a person's susceptibility to IBD and its potential severity.

"A handful ...

Drug shows promise against Sudan strain of Ebola in mice

2014-08-28

August 28, 2014 — (BRONX, NY) — Researchers from Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and other institutions have developed a potential antibody therapy for Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), one of the two most lethal strains of Ebola. A different strain, the Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV), is now devastating West Africa. First identified in 1976, SUDV has caused numerous Ebola outbreaks (most recently in 2012) that have killed more than 400 people in total. The findings were reported in ACS Chemical Biology.

Between 30 and 90 percent of people infected with Ebola ...

NASA sees a weaker Tropical Storm Marie

2014-08-28

When NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of what is now Tropical Storm Marie, weakened from hurricane status on August 28, the strongest thunderstorms were located in the southern quadrant of the storm.

NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of Marie on August 28 at 11 a.m. EDT. Bands of thunderstorms circled the storm especially to the north. The National Hurricane Center noted that Marie has continued to produce a small area of convection (rising air that forms the thunderstorms that make up Marie) south and east of the center during some hours on the ...

DeVincenzo study breakthrough in RSV research

2014-08-28

MEMPHIS, Tenn. – The New England Journal of Medicine published research results on Aug. 21 from a clinical trial of a drug shown to safely reduce the viral load and clinical illness of healthy adult volunteers intranasally infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center researcher Infectious Disease Specialist John DeVincenzo, MD, is lead author of this study.

RSV is the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in young children in the United States and worldwide. ...

Small molecule acts as on-off switch for nature's antibiotic factory

2014-08-28

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists have identified the developmental on-off switch for Streptomyces, a group of soil microbes that produce more than two-thirds of the world's naturally derived antibiotic medicines.

Their hope now would be to see whether it is possible to manipulate this switch to make nature's antibiotic factory more efficient.

The study, appearing August 28 in Cell, found that a unique interaction between a small molecule called cyclic-di-GMP and a larger protein called BldD ultimately controls whether a bacterium spends its time in a vegetative state or ...

Second-hand e-cig smoke compared to regular cigarette smoke

2014-08-28

E-cigarettes are healthier for your neighbors than traditional cigarettes, but still release toxins into the air, according to a new study from USC.

Scientists studying secondhand smoke from e-cigarettes discovered an overall 10-fold decrease in exposure to harmful particles, with close-to-zero exposure to organic carcinogens. However, levels of exposure to some harmful metals in second-hand e-cigarette smoke were found to be significantly higher.

While tobacco smoke contains high levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – cancer-causing organic compounds – the level ...

Healthy Moms program helps women who are obese limit weight gain during pregnancy

2014-08-28

PORTLAND, Ore., August 28, 2014 — A new study finds that women who are obese can limit their weight gain during pregnancy using conventional weight loss techniques including attending weekly group support meetings, seeking advice about nutrition and diet, and keeping food and exercise journals.

Results of the Healthy Moms study, published in Obesity, also show that obese women who limit their weight gain during pregnancy are less likely to have large-for-gestational age babies which can complicate delivery and increase the baby's risk of becoming obese later in life.

"Most ...