(Press-News.org) Anyone who enjoys biting into a sweet, fleshy peach can now give thanks to the people who first began domesticating this fruit: Chinese farmers who lived 7,500 years ago.

In a study published today in PLOS ONE, Gary Crawford, a U of T Mississauga anthropology professor, and two Chinese colleagues propose that the domestic peaches enjoyed worldwide today can trace their ancestry back at least 7,500 years ago to the lower Yangtze River Valley in Southern China, not far from Shanghai. The study, headed by Yunfei Zheng from the Zhejiang Institute of Archeology in China's Zhejiang Province, was done in collaboration with Crawford and X. Chen, another researcher at the Zhejang Institute.

"Previously, no one knew where peaches were domesticated," said Crawford. "None of the botanical literature suggested the Yangtze Valley, although many people thought that it happened somewhere in China."

Radiocarbon dating of ancient peach stones (pits) discovered in the Lower Yangtze River Valley indicates that the peach seems to have been diverged from its wild ancestors as early as 7,500 years ago.

Archeologists have a good understanding of domestication – conscious breeding for traits preferred by people– of annual plants such as grains (rice, wheat, etc.), but the role of trees in early farming and how trees were domesticated is not well documented. Unlike most trees, the peach matures very quickly, producing fruit within two to three years, so selection for desirable traits could become apparent relatively quickly. The problem that Crawford and his colleagues faced was how to recognize the selection process in the archeological record.

Peach stones are well represented at archeological sites in the Yangtze valley, so they compared the size and structure of the stones from six sites that spanned a period of roughly 5,000 years. By comparing the size of the stones from each site, they were able to discern peaches growing significantly larger over time in the Yangtze valley, demonstrating that domestication was taking place. The first peach stones in China most similar to modern cultivated forms are from the Liangzhu culture, which flourished 4,300 to 5300 years ago.

"We're suggesting that very early on, people understood grafting and vegetative reproduction, because it sped up selection," Crawford said. "They had to have been doing such work, because seeds have a lot of genetic variability, and you don't know if a seed will produce the same fruit as the tree that produced it. It's a gamble. If they simply started grafting, it would guarantee the orchard would have the peaches they wanted."

Crawford and his colleagues think that it took about 3,000 years before the domesticated peach resembled the fruit we know today.

"The peaches we eat today didn't grow in the wild," Crawford added. "Generation after generation kept selecting the peaches they enjoyed. The product went from thinly fleshed, very small fruit to what we have today. Peaches produce fruit over an extended season today but in the wild they have a short season. People must have selected not only for taste and fruit size, but for production time too."

Discovering more about the origins of domesticated peaches tells us more about our human ancestors, too, Crawford noted.

Crops such as domesticated peaches indicate that early people weren't passive in dealing with the environment. Not only did they understand grain production, but the woodlands and certain trees were being manipulated early on.

"There is a general sense that people in the past were not as smart as we are," said Crawford. "The reality is that they were modern humans with the brain capacity and talents that we have now.

"People have been changing the environment to suit their needs for a very long time, and the domestication of peaches helps us understand this."

INFORMATION:

It's the pits: Ancient peach stones offer clues to fruit's origins

2014-09-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Like weeds of the sea, 'brown tide' algae exploit nutrient-rich coastlines

2014-09-05

The sea-grass beds of Long Island's Great South Bay once teemed with shellfish. Clams, scallops and oysters filtered nutrients from the water and flushed money through the local economy. But three decades after the algae that cause brown tides first appeared here, much of the sea grass and the bounty it used to provide is gone.

Spring on eastern Long Island is now marked by dense blooms of Aureococcus anophagefferens, which turn estuaries like Great South Bay the color of mud and crowd out native sea grass and stunt or poison shellfish. For years, researchers have puzzled ...

Past sexual assault triples risk of future assault for college women

2014-09-05

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Disturbing news for women on college campuses: a new study from the University at Buffalo Research Institute on Addictions (RIA) indicates that female college students who are victims of sexual assault are at a much higher risk of becoming victims again.

In fact, researchers found that college women who experienced severe sexual victimization were three times more likely than their peers to experience severe sexual victimization the following year.

RIA researchers followed nearly 1,000 college women, most age 18 to 21, over a five-year period, studying ...

Breast cancer specialist reports advance in treatment of triple-negative breast cancer

2014-09-05

William M. Sikov, a medical oncologist in the Breast Health Center and associate director for clinical research in the Program in Women's Oncology at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, served as study chair and lead author for a recently-published major national study that could lead to improvements in outcomes for women with triple-negative breast cancer, an aggressive form of the disease that disproportionately affects younger women.

"Impact of the Addition of Carboplatin and/or Bevacizumab to Neoadjuvant Once-Per-Week Paclitaxel Followed by Dose-Dense Doxorubicin ...

Syracuse University physicists explore biomimetic clocks

2014-09-05

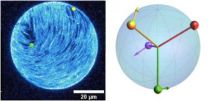

Working with a team of scientists from the Technical University of Munich (TU Munich), Brandeis University, and Leiden University in the Netherlands, M. Cristina Marchetti and Mark Bowick, professors in the Soft Matter Program in the Syracuse University College of Arts and Sciences, have engineered and studied "active vesicles." These purely synthetic, molecularly thin sacs are capable of transforming energy, injected at the microscopic level, into organized, self-sustained motion.

Their findings are the subject of a cover-story in the Sept. 5 issue of Science magazine.

The ...

Thousands of nuclear loci via target enrichment and genome skimming

2014-09-05

The use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies in phylogenetic studies is in a state of continual development and improvement. Though the botanically-inclined have historically focused on markers from the chloroplast genome, the importance of incorporating nuclear data is becoming increasingly evident. Nuclear genes provide not only the potential to resolve relationships between closely related taxa, but also the means to disentangle hybridization and better understand incongruences caused by incomplete lineage sorting and introgression.

By harnessing the power ...

Social support: How to thrive through close relationships

2014-09-05

PITTSBURGH—Close and caring relationships are undeniably linked to health and well-being for all ages. Previous research has shown that individuals with supportive and rewarding relationships have better physical and mental health and lower mortality rates. However, exactly how meaningful relationships affect health has remained less clear.

In a new paper, Carnegie Mellon University's Brooke Feeney and University of California, Santa Barbara's Nancy L. Collins detail specific interpersonal processes that explain how close relationships help individuals thrive. Published ...

Dietary recommendations may be tied to increased greenhouse gas emissions

2014-09-05

ANN ARBOR—If Americans altered their menus to conform to federal dietary recommendations, emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases tied to agricultural production could increase significantly, according to a new study by University of Michigan researchers.

Martin Heller and Gregory Keoleian of U-M's Center for Sustainable Systems looked at the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production of about 100 foods, as well as the potential effects of shifting Americans to a diet recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

They found that if Americans adopted ...

Disease in a dish approach could aid Huntington's disease discovery

2014-09-05

Creating induced pluripotent stem cells or iPS cells allows researchers to establish "disease in a dish" models of conditions ranging from Alzheimer's disease to diabetes. Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center have now applied the technology to a model of Huntington's disease (HD) in transgenic nonhuman primates, allowing them to conveniently assess the efficacy of potential therapies on neuronal cells in the laboratory.

The results were published in Stem Cell Reports.

"A highlight of our model is that our progenitor cells and neurons developed cellular ...

Novel immunotherapy vaccine decreases recurrence in HER2 positive breast cancer patients

2014-09-05

A new breast cancer vaccine candidate, (GP2), provides further evidence of the potential of immunotherapy in preventing disease recurrence. This is especially the case for high-risk patients when it is combined with a powerful immunotherapy drug. These findings are being presented by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center at the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology's Breast Cancer Symposium in San Francisco.

One of only a few vaccines of its kind in development, GP2 has been shown to be safe and effective for breast cancer patients, reducing recurrence ...

UT Southwestern researchers find new gene mutations for Wilms Tumor

2014-09-05

DALLAS – Sept. 5, 2014 – Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center and the Gill Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Children's Medical Center, Dallas, have made significant progress in defining new genetic causes of Wilms tumor, a type of kidney cancer found only in children.

Wilms tumor is the most common childhood genitourinary tract cancer and the third most common solid tumor of childhood.

"While most children with Wilms tumor are thankfully cured, those with more aggressive tumors do poorly, and we are increasingly concerned about the long-term adverse ...