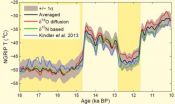

(Press-News.org) One of the common perceptions about the climate is that the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, solar radiation and temperature follow each other – the more solar radiation and the more carbon dioxide, the hotter the temperature. This correlation is also seen in the Greenland ice cores that are drilled through the approximately three kilometer thick ice sheet. But during a period of several thousand years up until the last ice age ended approximately 12,000 years ago, this pattern did not fit and this was a mystery to researchers. Now researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute have solved this mystery using new analytical techniques. The results are published in the prestigious scientific journal Science.

The Greenland ice sheet is an archive of knowledge about the Earth's climate more than 125,000 years back in time. The ice was formed by the precipitation that fell as snow from the clouds and remained year after year, gradually being compressed into ice. By drilling down through the approximately three kilometer thick ice sheet, the researchers draw up ice cores, which provide detailed knowledge of the climate of the past annual layer after annual layer. By measuring the content of the special oxygen isotope O18 in the ice cores, you can get information about the temperature in the past climate, year by year.

But something didn't fit. In Greenland, the end of the Ice Age started 15,000 years ago and the temperature rose quickly. Then it became colder again until 12,000 years ago, when there was again a rapid rise in temperature. The first rise in temperature is called the Bølling-Allerød interstadial and the second is called the Holocene interglacial.

Temperatures contrary to expectations

"We could see that the concentration of carbon dioxide and solar radiation was higher during the cold period between the two warm periods compared with the cold period before the first warming 15,000 years ago. But the temperature measurements based on the oxygen isotope O18 showed that the period between the two warm periods was colder than the cold period before the first warming 15,000 years ago. This was the exact opposite of what you would expect," explains postdoc Vasileios Gkinis, Centre for Ice and Climate, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen.

The researchers investigated ice cores from three different Greenland ice cores: the NEEM project, the NGRIP project and the GISP 2 project. But amount of the oxygen isotope O18 was not enough to reconstruct period temperatures in detail or their geographic distribution.

To get more detailed temperature data, the researchers used two relatively new methods of investigation, both of which examine the layer of compressed granular snow that is formed between the top layer of soft and fluffy snow and the layer deeper down in the ice sheet, where the compressed snow has been turned into ice. This process of transforming the fluffy snow into hard ice is physical and both the thickness and the movement of the water molecules are dependent on the temperature.

"With the first method, we measured the nitrogen content and by measuring the relationship between the two isotopes of nitrogen, N15 and N14, we could reconstruct the thickness of the compressed snow 19,000 years back in time," explains Vasileios Gkinis.

The second method involved measuring the spread of air with water molecules with different isotope composition in the layers with the compressed snow. This process of smoothing the original water isotope variations from precipitation is dependent on the temperature, as the water molecules in vapour form are more mobile at warmer temperatures.

Temperatures 'fall into place'

Data for the spread of the water molecules in the individual annual layers in the Greenland ice cores has thus made it possible to calculate the temperature in the layers with compressed snow 19,000 years back in time.

"What we discovered was that the previous temperature curve, which was only based on the measurements of the oxygen isotope O18, was inaccurate. The oxygen temperature curve said that the climate in central Greenland was colder around 12,000 years ago than around 15,000 years ago, despite the fact that two key climate drivers – carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and solar radiation – would suggest the opposite. With our new, more direct reconstruction, we have been able to show that the climate in central Greenland was actually warmer around 12,000 years ago compared to 15,000 years ago. So the temperatures actually follow the solar radiation and the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. We estimate that the temperature difference was 2-6 degrees," says Bo Vinther, Associate Professor at the Centre for Ice and Climate at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen.

INFORMATION:

See film about NEEM icecore project: http://www.nbi.ku.dk/english/sciencexplorer/earth_and_climate/secret_of_the_ice1/video/

For more information please contact:

Vasileios Gkinis

Centre for Ice and Climate

Niels Bohr Institute

University of Copenhagen

+45 6063-5297

v.gkinis@nbi.ku.dk

Bo Vinther

Associate Professor

Centre for Ice and Climate

Niels Bohr Institute

University of Copenhagen

+45 3532-0518

bo@gfy.ku.dk

Past temperature in Greenland adjusted

2014-09-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

WHO-commissioned report on e-cigarettes misleading, say experts

2014-09-05

World leading tobacco experts argue that a recently published World Health Organization (WHO)-commissioned review of evidence on e-cigarettes contains important errors, misinterpretations and misrepresentations putting policy-makers and the public in danger of foregoing the potential public health benefits of e-cigarettes.

The authors, writing today in the journal Addiction, analyse the WHO-commissioned Background Paper on E-cigarettes, which looks to have been influential in the recently published WHO report calling for greater regulation of e-cigarettes.

Professor ...

Visualizing plastic changes to the brain

2014-09-05

Tinnitus, migraine, epilepsy, depression, schizophrenia, Alzheimer's: all these are examples of diseases with neurological causes, the treatment and study of which is more and more frequently being carried out by means of magnetic stimulation of the brain. However, the method's precise mechanisms of action have not, as yet, been fully understood. The work group headed by PD Dr Dirk Jancke from the Institut für Neuroinformatik was the first to succeed in illustrating the neuronal effects of this treatment method with high-res images.

Painless Therapy

Transcranial magnetic ...

Harvard and Cornell researchers develop untethered, autonomous soft robot

2014-09-05

New Rochelle, NY, September 4, 2014--Imagine a non-rigid, shape-changing robot that walks on four "legs," can operate without the constraints of a tether, and can function in a snowstorm, move through puddles of water, and even withstand limited exposure to flames. Harvard advanced materials chemist George Whitesides, PhD and colleagues describe the mobile, autonomous robot they have created in Soft Robotics, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available on the Soft Robotics website.

In "A Resilient, Untethered Soft Robot," ...

Study: Viral infection in nose can trigger middle ear infection

2014-09-05

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – Sept. 5, 2014 – Middle ear infections, which affect more than 85 percent of children under the age of 3, can be triggered by a viral infection in the nose rather than solely by a bacterial infection, according to researchers at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

By simultaneously infecting the nose with a flu virus and a bacterium that is one of the leading causes of ear infections in children, the researchers found that the flu virus inflamed the nasal tissue and significantly increased both the number of bacteria and their propensity to travel ...

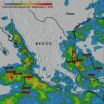

NASA adds up heavy rainfall from Hurricane Norbert

2014-09-05

As Hurricane Norbert continued dropping heavy amounts of rainfall on Mexico's Baja California on September 5, NASA's TRMM satellite calculated the rain that had already fallen.

From its orbit in space, the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite has the capability of determining how much rainfall has occurred over given areas. Data from TRMM was compiled into a rainfall map that showed the rainfall generated from Tropical Storm Dolly and Hurricane Norbert from August 28 through September 4, 2014.

Tropical storm Dolly dissipated quickly after coming ashore ...

It's the pits: Ancient peach stones offer clues to fruit's origins

2014-09-05

Anyone who enjoys biting into a sweet, fleshy peach can now give thanks to the people who first began domesticating this fruit: Chinese farmers who lived 7,500 years ago.

In a study published today in PLOS ONE, Gary Crawford, a U of T Mississauga anthropology professor, and two Chinese colleagues propose that the domestic peaches enjoyed worldwide today can trace their ancestry back at least 7,500 years ago to the lower Yangtze River Valley in Southern China, not far from Shanghai. The study, headed by Yunfei Zheng from the Zhejiang Institute of Archeology in China's ...

Like weeds of the sea, 'brown tide' algae exploit nutrient-rich coastlines

2014-09-05

The sea-grass beds of Long Island's Great South Bay once teemed with shellfish. Clams, scallops and oysters filtered nutrients from the water and flushed money through the local economy. But three decades after the algae that cause brown tides first appeared here, much of the sea grass and the bounty it used to provide is gone.

Spring on eastern Long Island is now marked by dense blooms of Aureococcus anophagefferens, which turn estuaries like Great South Bay the color of mud and crowd out native sea grass and stunt or poison shellfish. For years, researchers have puzzled ...

Past sexual assault triples risk of future assault for college women

2014-09-05

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Disturbing news for women on college campuses: a new study from the University at Buffalo Research Institute on Addictions (RIA) indicates that female college students who are victims of sexual assault are at a much higher risk of becoming victims again.

In fact, researchers found that college women who experienced severe sexual victimization were three times more likely than their peers to experience severe sexual victimization the following year.

RIA researchers followed nearly 1,000 college women, most age 18 to 21, over a five-year period, studying ...

Breast cancer specialist reports advance in treatment of triple-negative breast cancer

2014-09-05

William M. Sikov, a medical oncologist in the Breast Health Center and associate director for clinical research in the Program in Women's Oncology at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, served as study chair and lead author for a recently-published major national study that could lead to improvements in outcomes for women with triple-negative breast cancer, an aggressive form of the disease that disproportionately affects younger women.

"Impact of the Addition of Carboplatin and/or Bevacizumab to Neoadjuvant Once-Per-Week Paclitaxel Followed by Dose-Dense Doxorubicin ...

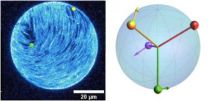

Syracuse University physicists explore biomimetic clocks

2014-09-05

Working with a team of scientists from the Technical University of Munich (TU Munich), Brandeis University, and Leiden University in the Netherlands, M. Cristina Marchetti and Mark Bowick, professors in the Soft Matter Program in the Syracuse University College of Arts and Sciences, have engineered and studied "active vesicles." These purely synthetic, molecularly thin sacs are capable of transforming energy, injected at the microscopic level, into organized, self-sustained motion.

Their findings are the subject of a cover-story in the Sept. 5 issue of Science magazine.

The ...