(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (Sep. 10. 2014) – With the completion of the sequencing and analysis of the gibbon genome, scientists now know more about why this small ape has a rapid rate of chromosomal rearrangements, providing information that broadens understanding of chromosomal biology.

Chromosomes, essentially the packaging that encases the genetic information stored in the DNA sequence, are fundamental to cellular function and the transmission of genetic information from one generation to the next. Chromosome structure and function is also intimately related to human genetic diseases, especially cancer.

The sequence and analysis of the gibbon genome (all the chromosomes) was published today in the journal Nature and led by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University, the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center and the Washington University School of Medicine's Genome Institute.

"Everything we learn about the genome sequence of this particular primate and others analyzed in the recent past helps us to understand human biology in a more detailed and complete way," said Dr. Jeffrey Rogers, associate professor in the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor and a lead author on the report. "The gibbon sequence represents a branch of the primate evolutionary tree that spans the gap between the Old World Monkeys and great apes and has not yet been studied in this way. The new genome sequence provides important insight into their unique and rapid chromosomal rearrangements."

For years, experts have known that gibbon chromosomes evolve quickly and have many breaks and rearrangements, but up until now there has been no explanation why, Rogers said. The genome sequence helps to explain the genetic mechanism unique to gibbons that results in these large scale rearrangements.

The sequencing was led by Dr. Kim Worley, professor in the Human Genome Sequencing Center, and Rogers, both of Baylor and Drs. Wesley Warren and Richard Wilson of Washington University.

The analysis was led by Dr. Lucia Carbone, an assistant professor of behavioral neuroscience in the OHSU School of Medicine and an assistant scientist in the Division of Neuroscience at OHSU's Oregon National Primate Research Center. Carbone is an expert in the study of gibbons and the lead and corresponding author on the report.

"We do this work to learn as much as we can about gibbons, which are some of the rarest species on the planet," said Carbone. "But we also do this work to better understand our own evolution and get some clues on the origin of human diseases."

Chromosomal biology

Chromosomes play an essential role in the packaging of DNA, Worley said. "There are 3 billion base pairs of DNA in every cell and it is packaged into 23 pairs of chromosomes," said Worley, also a lead author on the report.

When there are rearrangements in chromosomes, the genes and gene regulation are often disrupted or broken, said Worley.

"Cancer is clearly the biggest medical example of the impact of chromosome rearrangements. The gibbon sequence gives us more insight into this process," said Worley. "There are also a number of other genetic diseases that result from these events."

Rearrangements

The number of chromosomal rearrangements in the gibbons is remarkable, Rogers said. "It is like the genome just exploded and then was put back together," he said. "Up until recently, it has been impossible to determine how one human chromosome could be aligned to any gibbon chromosome because there are so many rearrangements."

Repeat element

The sequencing project revealed a novel and unique genetic repeat element (segments of DNA that occur in multiple copies throughout the genome) that is inserted into genes associated with the maintenance of chromatin structure.

Repeat elements have the capability to disrupt a gene and change their biological function, Worley said. In the gibbons, the team identified the LAVA element - a novel repeat element that emerged exclusively in gibbons and preferentially hits genes involved in chromosome segregation (an essential step in cell division, where chromosomes pair off with their similar homologous chromosome.)

"This explains why the gibbons have undergone so much change," said Rogers. "Similar disruptions cause disease, which is why everything we learn from this helps us better understand human biology and chromosomal structures."

INFORMATION:

Collaborating institutions include Nabsys Inc., in Providence, RI; University of Arizona in Tucson; University of Pompeu Fabra/CSIC, ICREA at Institut de Biologia Evolutiva, Barcelona, Spain; University of Washington,Seattle, WA; Howard Hughes Medical Institute; European Molecular Biology Laboratory- European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus in Hinxton, United Kingdom; Leibniz Institute for Primate Research, Gene Bank of Primates, German Primate Center, Göttingen, Germany; Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus in Hinxton, United Kingdom; University of Bari, Dipartimento di Biologia, Bari, Italy; Louisiana State University, Department of Biological Sciences, Baton Rouge, LA; University of Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France; The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Baltimore, MD; University of Utah, Salt Lake City; Texas A&M University, Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, College Station; Babes-Bolyai-University, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research in Bio-Nano-Sciences, Molecular Biology Center, Cluj-Napoca, Romania; Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, BACPAC Resources, Oakland, Calif; University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, Aurora, CO; Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany; Centro Nacional de Análisis Genómico (CNAG), Barcelona, Spain; Indiana University, School of Informatics and Computing, Bloomington, IN; Washington University School of Medicine, The Genome Institute, St. Louis, MO; Institute for system biology, Seattle; The Pennsylvania State University, Department of Anthropology, University Park, PA; University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Developmental Biology-Department of Computational and Systems Biology, Pittsburg, PA; Harvard Medical School, Department of Genetics, Boston, MA; University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK-Cambridge Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom; University of San Francisco, Gladstone Institutes, Institute for Human Genetics - Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, San Francisco, Calif; Paul Ehrlich Institute, Division of Medical Biotechnology, Lagen, Germany; Gibbon Conservation Center, Santa Clarita, CA; Louisiana State University, School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Baton Rouge, LA; University of California San Francisco, Institute for Human Genetics, San Francisco, CA; Stony Brook University, Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook, NY.

Funding for this work was provided by the National Human Genome Research Institute (U54 HG003273; U54 HG003079; National Institutes of Health ( P30 AA019355 and NIH/NCRR P51 RR000163; R01_HG005226; National Library of Medicine Biomedical Informatics Research Training Program (R01 GM59290, U41 HG007497-01, R01 MH081203, HG002385; National Science Foundation (CNS-1126739); European Research Council (260372): Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (BFU2011-28549): Ministry of National Education (PN-II-ID-PCE-2012-4-0090: EMBO Young Investigator Award; University of Cambridge; Cancer Research UK; Commonwealth Scholarship Commission.

Glenna Picton

713-798-4710

picton@bcm.edu

http://www.bcm.edu/news

Gibbon genome sequence deepens understanding of primates rapid chromosomal rearrangements

Gibbon genome sequence deepens understanding of primates rapid chromosomal rearrangements

2014-09-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mysterious quasar sequence explained

2014-09-10

Pasadena, CA—Quasars are supermassive black holes that live at the center of distant massive galaxies. They shine as the most luminous beacons in the sky across the entire electromagnetic spectrum by rapidly accreting matter into their gravitationally inescapable centers. New work from Carnegie's Hubble Fellow Yue Shen and Luis Ho of the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics (KIAA) at Peking University solves a quasar mystery that astronomers have been puzzling over for 20 years. Their work, published in the September 11 issue of Nature, shows that most observed ...

Researchers discover 3 extinct squirrel-like species

2014-09-10

Paleontologists have described three new small squirrel-like species that place a poorly understood Mesozoic group of animals firmly in the mammal family tree. The study, led by scientists at the American Museum of Natural History and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, supports the idea that mammals—an extremely diverse group that includes egg-laying monotremes such as the platypus, marsupials such as the opossum, and placentals like humans and whales—originated at least 208 million years ago in the late Triassic, much earlier than some previous research suggests. The study ...

Fish and fatty acid consumption associated with lower risk of hearing loss in women

2014-09-10

BOSTON, MA – Researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital found that consumption of two or more servings of fish per week was associated with a lower risk of hearing loss in women. Findings of the new study Fish and Fatty Acid Consumption and Hearing Loss study led by Sharon G. Curhan, MD, BWH Channing Division of Network Medicine, are published online on September 10 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (AJCN).

"Acquired hearing loss is a highly prevalent and often disabling chronic health condition," stated Curhan, corresponding author. "Although a decline ...

Research identifies drivers of rich bird biodiversity in Neotropics

2014-09-10

An international team of researchers is challenging a commonly held view that explains how so many species of birds came to inhabit the Neotropics, an area rich in rain forest that extends from Mexico to the southernmost tip of South America. The new research, published today in the journal Nature, suggests that tropical bird speciation is not directly linked to geological and climate changes, as traditionally thought, but is driven by movements of birds across physical barriers such as mountains and rivers that occur long after those landscapes' geological origins.

"The ...

UT Arlington research uses nanotechnology to help cool electrons with no external sources

2014-09-10

A team of researchers has discovered a way to cool electrons to −228 °C without external means and at room temperature, an advancement that could enable electronic devices to function with very little energy.

The process involves passing electrons through a quantum well to cool them and keep them from heating.

The team details its research in "Energy-filtered cold electron transport at room temperature," which is published in Nature Communications on Wednesday, Sept. 10.

"We are the first to effectively cool electrons at room temperature. Researchers have done ...

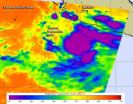

NASA catches birth of Tropical Storm Odile

2014-09-10

The Eastern Pacific Ocean continues to turn out tropical cyclones and NASA's Aqua satellite caught the birth of the fifteenth tropical depression on September 10 and shortly afterward, it strengthened into a tropical storm and was renamed Odile.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured infrared data on Tropical Depression 15-E on September 10 at 8:53 UTC (4:53 a.m. EDT) when it developed. The National Hurricane Center named the depression at 5 a.m. EDT, when the center was located near latitude 14.4 north and ...

A new way to look at diabetes and heart risk

2014-09-10

People with diabetes who appear otherwise healthy may have a six-fold higher risk of developing heart failure regardless of their cholesterol levels, new Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health research suggests.

In nearly 50 percent of people with diabetes in their study, researchers employing an ultra-sensitive test were able to identify minute levels of a protein released into the blood when heart cells die. The finding suggests that people with diabetes may be suffering undetectable – but potentially dangerous – heart muscle damage possibly caused by their ...

Study: Sports broadcasting gender roles echoed on Twitter

2014-09-10

Twitter provides an avenue for female sports broadcasters to break down gender barriers, yet it currently serves to express their subordinate sports media roles.

This is the key finding of a new study by Clemson University researchers and published in the most recent issue of Journal of Sports Media.

"Social media has been embraced by the sports world at an extraordinary pace and has become a viable avenue for sports broadcasters to redefine their roles as celebrities," said Melinda Weathers, lead author on the study and assistant professor of communication studies ...

Cyberbullying increases as students age

2014-09-10

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — As students' age they are verbally and physically bullied less but cyberbullied more, non-native English speakers are not bullied more often than native English speakers and bullying increases as students' transition from elementary to middle school.

Those are among the findings of a wide-ranging paper, "Examination of the Change in Latent Statuses in Bullying Behaviors Across Time," recently published in the journal School Psychology Quarterly.

Authors of the paper are: Cixin Wang, an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside's ...

Even small stressors may be harmful to men's health, new OSU research shows

2014-09-10

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Older men who lead high-stress lives, either from chronic everyday hassles or because of a series of significant life events, are likely to die earlier than the average for their peers, new research from Oregon State University shows.

"We're looking at long-term patterns of stress – if your stress level is chronically high, it could impact your mortality, or if you have a series of stressful life events, that could affect your mortality," said Carolyn Aldwin, director of the Center for Healthy Aging Research in the College of Public Health and Human ...