(Press-News.org) Blame the "hot Jupiters."

These large, gaseous exoplanets (planets outside our solar system) can make their suns wobble when they wend their way through their own solar systems to snuggle up against their suns, according to new Cornell University research to be published in Science, Sept. 11.

Images: https://cornell.box.com/lai

"Although the planet's mass is only one-thousandth of the mass of the sun, the stars in these other solar systems are being affected by these planets and making the stars themselves act in a crazy way," said Dong Lai, Cornell professor of astronomy and senior author on the research, "Chaotic Dynamics of Stellar Spin in Binaries and the Production of Misaligned Hot Jupiters." Physics graduate student Natalia I. Storch (lead author) and astronomy graduate student Kassandra R. Anderson are co-authors.

In our solar system, the sun's rotation axis is approximately aligned with the orbital axis of all the planets. The orbital axis is perpendicular to the flat plane in which the planets revolve around the sun. In solar systems with hot Jupiters, recent observations have revealed that the orbital axis of these planets is misaligned with the rotation axis of their host star. In the last few years, astronomers have been puzzled by spin-orbit misalignment between the star and the planets.

Roasting like marshmallows on an open fire, hot Jupiters – large gaseous planets dispensed throughout the universe in other solar systems – wander from distant places to orbit extraordinarily close to their own suns. Partner binary stars, some as far as hundreds of astronomical units (an astronomical unit is 93 million miles, the distance between Earth and the sun,) influence through gravity the giant Jupiter-like planets and cause them to falter into uncommon orbits; that, in turn, causes them to migrate inward close to their sun, Lai said.

"When exoplanets were first found in the 1990s, it was large planets like Jupiter that were discovered. It was surprising that such giant planets can be so close to parent star," Lai said. "Our own planet Mercury is very close to our sun. But these hot Jupiters are much closer to their suns than Mercury."

By simulating the dynamics of these exotic planetary systems, the Cornell astronomers showed that when the Jupiter-like planet approaches its host star, the planet can force the star's spin axis to precess (that is, change the orientation of their rotational axis), much like a wobbling, spinning top.

"Also, it can make the star's spin axis change direction in a rather complex – or even a chaotic – way," said Lai. "This provides a possible explanation to the observed spin-orbit misalignments, and will be helpful for understanding the origin of these enigmatic planets."

Another interesting feature of the Cornell work is that the chaotic variation of the star's spin axis resembles other chaotic phenomena found in nature, such as weather and climate.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and by NASA.

'Hot Jupiters' provoke their own host suns to wobble

2014-09-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Diversified farming practices might preserve evolutionary diversity of wildlife

2014-09-11

As humans transform the planet to meet our needs, all sorts of wildlife continue to be pushed aside, including many species that play key roles in Earth's life-support systems. In particular, the transformation of forests into agricultural lands has dramatically reduced biodiversity around the world.

A new study by scientists at Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, in this week's issue of Science shows that evolutionarily distinct species suffer most heavily in intensively farmed areas. They also found, however, that an extraordinary amount of evolutionary ...

You can classify words in your sleep

2014-09-11

When people practice simple word classification tasks before nodding off—knowing that a "cat" is an animal or that "flipu" isn't found in the dictionary, for example—their brains will unconsciously continue to make those classifications even in sleep. The findings, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 11, show that some parts of the brain behave similarly whether we are asleep or awake and pave the way for further studies on the processing capacity of our sleeping brains, the researchers say.

"We show that the sleeping brain can be far more ...

Gut microbes determine how well the flu vaccine works

2014-09-11

Annual flu epidemics cause millions of cases of severe illness and up to half a million deaths every year around the world, despite widespread vaccination programs. A study published by Cell Press on September 11th in Immunity reveals that gut microbes play an important role in stimulating protective immune responses to the seasonal flu vaccine in mice, suggesting that differences in the composition of gut microbes in different populations may impact vaccine immunity. The study paves the way for global public health strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flu vaccine. ...

Stem cells help researchers understand how schizophrenic brains function

2014-09-11

Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), researchers have gained new insight into what may cause schizophrenia by revealing the altered patterns of neuronal signaling associated with this disease. They did so by exposing neurons derived from the hiPSCs of healthy individuals and of patients with schizophrenia to potassium chloride, which triggered these stem cells to release neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, that are crucial for brain function and are linked to various disorders. By discovering a simple method for stimulating hiPSCs to release neurotransmitters, ...

Intestinal bacteria needed for strong flu vaccine responses in mice

2014-09-11

Mice treated with antibiotics to remove most of their intestinal bacteria or raised under sterile conditions have impaired antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination, researchers have found.

The findings suggest that antibiotic treatment before or during vaccination may impair responses to certain vaccines in humans. The results may also help to explain why immunity induced by some vaccines varies in different parts of the world.

In a study to be published in Immunity, Bali Pulendran, PhD, and colleagues at Emory University demonstrate a dependency on gut ...

Our microbes are a rich source of drugs, UCSF researchers discover

2014-09-11

Bacteria that normally live in and upon us have genetic blueprints that enable them to make thousands of molecules that act like drugs, and some of these molecules might serve as the basis for new human therapeutics, according to UC San Francisco researchers who report their new discoveries in the September 11, 2014 issue of Cell.

The scientists purified and solved the structure of one of the molecules they identified, an antibiotic they named lactocillin, which is made by a common bacterial species, Lactobacillus gasseri, found in the microbial community within the vagina. ...

Cells put off protein production during times of stress

2014-09-11

DURHAM, N.C. -- Living cells are like miniature factories, responsible for the production of more than 25,000 different proteins with very specific 3-D shapes. And just as an overwhelmed assembly line can begin making mistakes, a stressed cell can end up producing misshapen proteins that are unfolded or misfolded.

Now Duke University researchers in North Carolina and Singapore have shown that the cell recognizes the buildup of these misfolded proteins and responds by reshuffling its workload, much like a stressed out employee might temporarily move papers from an overflowing ...

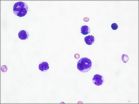

A non-toxic strategy to treat leukemia

2014-09-11

A study comparing how blood stem cells and leukemia cells consume nutrients found that cancer cells are far less tolerant to shifts in their energy supply than their normal counterparts. The results suggest that there could be ways to target leukemia metabolism so that cancer cells die but other cell types are undisturbed.

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine and the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology led the work, published in the journal Cell, in collaboration with ...

Scientists discover neurochemical imbalance in schizophrenia

2014-09-11

Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), researchers at Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at University of California, San Diego have discovered that neurons from patients with schizophrenia secrete higher amounts of three neurotransmitters broadly implicated in a range of psychiatric disorders.

The findings, reported online Sept. 11 in Stem Cell Reports, represent an important step toward understanding the chemical basis for schizophrenia, a chronic, severe and disabling brain disorder that affects an estimated one in 100 persons at some ...

Diverse gut bacteria associated with favorable ratio of estrogen metabolites

2014-09-11

Washington, DC—Postmenopausal women with diverse gut bacteria exhibit a more favorable ratio of estrogen metabolites, which is associated with reduced risk for breast cancer, compared to women with less microbial variation, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

Since the 1970s, it has been known that in addition to supporting digestion, the intestinal bacteria that make up the gut microbiome influence how women's bodies process estrogen, the primary female sex hormone. The colonies of bacteria ...