(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Early but promising tests in lab mice suggest that a bioengineered 'decoy' protein, administered intravenously, can halt the spread of cancer from the original tumor site. Years of subsequent tests...

Click here for more information.

A team of Stanford researchers has developed a protein therapy that disrupts the process that causes cancer cells to break away from original tumor sites, travel through the blood stream and start aggressive new growths elsewhere in the body.

This process, known as metastasis, can cause cancer to spread with deadly effect.

"The majority of patients who succumb to cancer fall prey to metastatic forms of the disease," said Jennifer Cochran, an associate professor of bioengineering who describes a new therapeutic approach in Nature Chemical Biology.

Today doctors try to slow or stop metastasis with chemotherapy, but these treatments are unfortunately not very effective and have severe side effects.

The Stanford team seeks to stop metastasis, without side effects, by preventing two proteins – Axl and Gas6 – from interacting to initiate the spread of cancer.

Axl proteins stand like bristles on the surface of cancer cells, poised to receive biochemical signals from Gas6 proteins.

When two Gas6 proteins link with two Axls, the signals that are generated enable cancer cells to leave the original tumor site, migrate to other parts of the body and form new cancer nodules.

To stop this process Cochran used protein engineering to create a harmless version of Axl that acts like a decoy. This decoy Axl latches on to Gas6 proteins in the blood stream and prevents them from linking with and activating the Axls present on cancer cells.

In collaboration with Professor Amato Giaccia, who heads the Radiation Biology Program in Stanford's Cancer Center, the researchers gave intravenous treatments of this bioengineered decoy protein to mice with aggressive breast and ovarian cancers.

Mice in the breast cancer treatment group had 78 percent fewer metastatic nodules than untreated mice. Mice with ovarian cancer had a 90 percent reduction in metastatic nodules when treated with the engineered decoy protein.

"This is a very promising therapy that appears to be effective and non-toxic in pre-clinical experiments," Giaccia said. "It could open up a new approach to cancer treatment."

Giaccia and Cochran are scientific advisors to Ruga Corp., a biotech startup in Palo Alto that has licensed this technology from Stanford. Further preclinical and animal tests must be done before determining whether this therapy is safe and effective in humans.

Greg Lemke, of the Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory at the Salk Institute, called this "a prime example of what bioengineering can do" to open up new therapeutic approaches to treat metastatic cancer.

"One of the remarkable things about this work is the binding affinity of the decoy protein," said Lemke, a noted authority on Axl and Gas6 who was not part of the Stanford experiments.

"The decoy attaches to Gas6 up to a hundredfold more effectively than the natural Axl," Lemke said. "It really sops up Gas6 and takes it out of action."

Directed Evolution

The Stanford approach is grounded on the fact that all biological processes are driven by the interaction of proteins, the molecules that fit together in lock-and-key fashion to perform all the tasks required for living things to function.

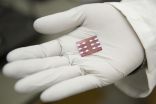

In nature proteins evolve over millions of years. But bioengineers have developed ways to accelerate the process of improving these tiny parts using technology called directed evolution. This particular application was the subject of the doctoral thesis of Mihalis Kariolis, a bioengineering graduate student in Cochran's lab.

Using genetic manipulation, the Stanford team created millions of slightly different DNA sequences. Each DNA sequence coded for a different variant of Axl.

The researchers then used high-throughput screening to evaluate over 10 million Axl variants. Their goal was to find the variant that bound most tightly to Gas6.

Kariolis made other tweaks to enable the bioengineered decoy to remain in the bloodstream longer and also to tighten its grip on Gas6, rendering the decoy interaction virtually irreversible.

Yu Rebecca Miao, a postdoctoral scholar in Giaccia's lab, designed the testing in animals and worked with Kariolis to administer the decoy Axl to the lab mice. They also did comparison tests to show that sopping up Gas6 resulted in far fewer secondary cancer nodules.

Irimpan Mathews, a protein crystallography expert at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, joined the research effort to help the team better understand the binding mechanism between the Axl decoy and Gas6.

Protein crystallography captures the interaction of two proteins in a solid form, allowing researchers to take X-ray-like images of how the atoms in each protein bind together. These images showed molecular changes that allowed the bioengineered Axl decoy to bind Gas6 far more tightly than the natural Axl protein.

Next steps

Years of work lie ahead to determine whether this protein therapy can be approved to treat cancer in humans. Bioprocess engineers must first scale up production of the Axl decoy to generate pure material for clinical tests. Clinical researchers must then perform additional animal tests in order to win approval for and to conduct human trials. These are expensive and time-consuming steps.

But these early, hopeful results suggest that the Stanford approach could become a non-toxic way to fight metastatic cancer.

Glenn Dranoff, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a leading researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, reviewed an advance copy of the Stanford paper but was otherwise unconnected with the research. "It is a beautiful piece of biochemistry and has some nuances that make it particularly exciting," Dranoff said, noting that tumors often have more than one way to ensure their survival and propagation.

Axl has two protein cousins, Mer and Tyro3, that can also promote metastasis. Mer and Tyro3 are also activated by Gas6.

"So one therapeutic decoy might potentially affect all three related proteins that are critical in cancer development and progression," Dranoff said.

INFORMATION:

Acknowledgments

Dr. Erinn Rankin, a postdoctoral fellow in the Giaccia lab, carried out proof of principle experiments that paved the way for this study.

Other co-authors on the Nature Chemical Biology paper include Douglas Jones, a former doctoral student, and Shiven Kapur, a postdoctoral scholar, both of Cochran's lab, who contributed to the protein engineering and structural characterization, respectively.

Cochran said Stanford's support for interdisciplinary research made this work possible.

Stanford ChEM-H Institute (Chemistry, Engineering & Medicine for Human Health) provided seed funds that allowed Cochran and Mathews to collaborate on protein structural studies.

The Stanford Wallace H. Coulter Translational Research Grant Program, which supports collaborations between engineers and medical researchers, supported the efforts of Cochran and Giaccia to apply cutting edge bioengineering techniques to this critical medical need.

Stanford researchers create 'evolved' protein that may stop cancer from spreading

Experimental therapy stopped the metastasis of breast and ovarian cancers in lab mice, pointing toward a safe and effective alternative to chemotherapy

2014-09-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Smallest possible diamonds form ultra-thin nanothreads

2014-09-21

VIDEO:

For the first time, scientists have discovered how to produce ultra-thin 'diamond nanothreads' that promise extraordinary properties, including strength and stiffness greater than that of today's strongest nanotubes and polymers....

Click here for more information.

For the first time, scientists have discovered how to produce ultra-thin "diamond nanothreads" that promise extraordinary properties, including strength and stiffness greater than that of today's strongest ...

New cancer drug target involving lipid chemical messengers

2014-09-19

PHILADELPHIA — More than half of human cancers have abnormally upregulated chemical signals related to lipid metabolism, yet how these signals are controlled during tumor formation is not fully understood.

Youhai Chen, PhD, MD, and Svetlana Fayngerts, PhD, both researchers in the department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and colleagues report that TIPE3, a newly described oncogenic protein, promotes cancer by targeting these pathways.

Lipid second messengers play cardinal roles in relaying and amplifying ...

Melanoma risk found to have genetic determinant

2014-09-19

(Lebanon, NH 9/18/14)— A leading Dartmouth researcher, working with The Melanoma Genetics Consortium, GenoMEL, an international research consortium, co-authored a paper published today in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute that proves longer telomeres increase the risk of melanoma.

"For the first time, we have established that the genes controlling the length of these telomeres play a part in the risk of developing melanoma," said lead author of the study Mark Iles, PhD, School of Medicine at the University of Leeds (UK).

Telomeres are a part of the genome ...

UChicago-Argonne National Lab team improves solar-cell efficiency

2014-09-19

New light has been shed on solar power generation using devices made with polymers, thanks to a collaboration between scientists in the University of Chicago's chemistry department, the Institute for Molecular Engineering, and Argonne National Laboratory.

Researchers identified a new polymer — a type of large molecule that forms plastics and other familiar materials — which improved the efficiency of solar cells. The group also determined the method by which the polymer improved the cells' efficiency. The polymer allowed electrical charges to move more easily throughout ...

Research predicts possible 6,800 new Ebola cases this month

2014-09-19

Tempe, Ariz. (Sept. 19, 2014) - New research published today in the online journal PLoS Outbreaks predicts new Ebola cases could reach 6,800 in West Africa by the end of the month if new control measures are not enacted.

Arizona State University and Harvard University researchers also discovered through modelling analysis that the rate of rise in cases significantly increased in August in Liberia and Guinea, around the time that a mass quarantine was put in place, indicating that the mass quarantine efforts may have made the outbreak worse than it would have been otherwise. ...

Domestic violence likely more frequent for same-sex couples

2014-09-19

CHICAGO --- Domestic violence occurs at least as frequently, and likely even more so, between same-sex couples compared to opposite-sex couples, according to a review of literature by Northwestern Medicine scientists.

Previous studies, when analyzed together, indicate that domestic violence affects 25 percent to 75 percent of lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals. However, a lack of representative data and underreporting of abuse paints an incomplete picture of the true landscape, suggesting even higher rates. An estimated one in four heterosexual women experience domestic ...

A better way to track emerging cell therapies using MRIs

2014-09-19

Cellular therapeutics – using intact cells to treat and cure disease – is a hugely promising new approach in medicine but it is hindered by the inability of doctors and scientists to effectively track the movements, destination and persistence of these cells in patients without resorting to invasive procedures, like tissue sampling.

In a paper published September 17 in the online journal Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh and elsewhere describe the first human tests of using ...

NASA catches a weaker Edouard, headed toward Azores

2014-09-19

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over the Atlantic Ocean and captured a picture of Tropical Storm Edouard as it continues to weaken. The National Hurricane Center expects Edouard to affect the western Azores over the next two days.

NASA's Aqua satellite flew over Tropical Storm Edouard on Sept. 18 at 1:45 p.m. EDT and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument took a visible picture that showed the eye had disappeared and the bulk of clouds pushed east of center.

At 5 a.m. EDT on Sept. 19, Edouard's maximum sustained winds had decreased to near ...

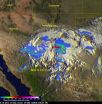

NASA, NOAA satellites show Odile's remnant romp through southern US

2014-09-19

Former Hurricane Odile may be a bad memory for Baja California, but the remnants have moved over New Mexico and Texas where they are expected to bring rainfall there. NASA's TRMM satellite measured Odile's heavy rainfall rates on Sept. 18, and NOAA's GOES-West satellite saw the clouds associated with the former storm continue to linger over the U.S. Southwest on Sept. 19.

The remnants of Hurricane Odile were dropping heavy rain in the area from southern Arizona to western Texas when NASA-JAXA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite flew over on September ...

NASA sees Tropical Storm playing polo with western Mexico

2014-09-19

Tropical Storm Polo is riding along the coast of western Mexico like horses in the game of his namesake. NASA's Aqua satellite saw Polo about 300 miles south-southeast of Baja California on its track north.

NASA's Aqua satellite flew over Polo on Sept. 18 at 4:35 p.m. EDT and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer captured a visible image of the storm that showed that much of the clouds, thunderstorms and showers were west and south of the center of circulation, and away from the coast. That's an indication that easterly wind shear had increased and were pushing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Hairdressers could be a secret weapon in tackling climate change, new research finds

Genetic risk for mental illness is far less disorder-specific than clinicians have assumed, massive Swedish study reveals

A therapeutic target that would curb the spread of coronaviruses has been identified

Modern twist on wildfire management methods found also to have a bonus feature that protects water supplies

AI enables defect-aware prediction of metal 3D-printed part quality

Miniscule fossil discovery reveals fresh clues into the evolution of the earliest-known relative of all primates

World Water Day 2026: Applied Microbiology International to hold Gender Equality and Water webinar

The unprecedented transformation in energy: The Third Energy Revolution toward carbon neutrality

Building on the far side: AI analysis suggests sturdier foundation for future lunar bases

Far-field superresolution imaging via k-space superoscillation

10 Years, 70% shift: Wastewater upgrades quietly transform river microbiomes

Why does chronic back pain make everyday sounds feel harsher? Brain imaging study points to a treatable cause

Video messaging effectiveness depends on quality of streaming experience, research shows

Introducing the “bloom” cycle, or why plants are not stupid

The Lancet Oncology: Breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women worldwide, with annual cases expected to reach over 3.5 million by 2050

Improve education and transitional support for autistic people to prevent death by suicide, say experts

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic could cut risk of major heart complications after heart attack, study finds

Study finds Earth may have twice as many vertebrate species as previously thought

NYU Langone orthopedic surgeons present latest clinical findings and research at AAOS 2026

New journal highlights how artificial intelligence can help solve global environmental crises

Study identifies three diverging global AI pathways shaping the future of technology and governance

Machine learning advances non targeted detection of environmental pollutants

ACP advises all adults 75 or older get a protein subunit RSV vaccine

New study finds earliest evidence of big land predators hunting plant-eaters

Newer groundwater associated with higher risk of Parkinson’s disease

New study identifies growth hormone receptor as possible target to improve lung cancer treatment

Routine helps children adjust to school, but harsh parenting may undo benefits

IEEE honors Pitt’s Fang Peng with medal in power engineering

SwRI and the NPSS Consortium release new version of NPSS® software with improved functionality

Study identifies molecular cause of taste loss after COVID

[Press-News.org] Stanford researchers create 'evolved' protein that may stop cancer from spreadingExperimental therapy stopped the metastasis of breast and ovarian cancers in lab mice, pointing toward a safe and effective alternative to chemotherapy