(Press-News.org) The millions of people who undergo major surgery each year have no way of knowing how long it will take them to recover from the operation. Some will feel better within days. For others, it will take a month or more. Right now, doctors can't tell individual patients which category they'll fit into.

Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that the activity level of a small set of immune cells during the first 24 hours after surgery provides strong clues to how quickly patients will bounce back from surgery-induced fatigue and pain, and be back on their feet again.

The finding, based on an in-depth analysis of blood samples drawn from middle-aged to older patients undergoing a hip-replacement procedure, is described in a study to be published Sept. 24 in Science Translational Medicine. The study may be the most comprehensive characterization to date of the immune system's response to trauma.

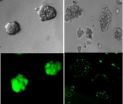

The Stanford researchers were able to make this discovery because they used a highly sensitive technology called single-cell mass cytometry. Developed in the laboratory of microbiology and immunology professor Garry Nolan, PhD, the method enables simultaneous monitoring of large numbers of biochemical features both on the surfaces of immune cells and within the cells, telling the scientists not only what kind of cells they are looking at but how active they are.

Strong Clues in First 24 Hours

"We learned that within the first 24 hours after surgery you can find strong clues in blood that reveal what shape a particular patient is going to be in two weeks later," said Martin Angst, MD, professor of anesthesiology, pain and perioperative medicine, who shared senior co-authorship of the study with Nolan.

The discovery could lead to the development of a personalized diagnostic blood test for predicting recovery after major surgery. (Stanford holds a provisional patent on the associated intellectual property.) Such a diagnostic could both help physicians make early decisions about which patients to put on enhanced recovery-optimizing regimens and help recovering patients know what to tell loved ones and bosses to expect. A full understanding of the molecular mechanisms identified in the study might even make it possible for clinicians to manipulate the immune system so as to foster faster recoveries.

Most of the more than 200 million surgical procedures performed annually worldwide are minor, Angst said. But in the United States alone, millions of those procedures — hip replacements, for example — are sufficiently traumatic to trigger profound inflammatory responses in patients.

Healing Versus Impeding

That initial blast of inflammation is essential to the healing process, said Angst. "You need to unleash the dragon," he said. "But you need to be able to ride it. Too much inflammation spells a protracted recovery." The immune system's components must continually rebalance their contributions in a dynamic that speeds rather than impedes healing.

A few years ago, Angst attended a talk by Nolan explaining mass cytometry, which permits simultaneous measurements of more than 50 different surface and internal features of single cells, while standard cell-sorting methods typically max out at 12-15 such measurements. This triggered a collaboration between Angst and Nolan, whose specialties were bridged by postdoctoral scholar Brice Gaudilliere, MD, PhD, now a clinical instructor in anesthesia. Gaudilliere shared lead authorship of the study with Gabriela Fragiadakis, a graduate student in Nolan's lab.

This ability to count so many features at once gives researchers a window to a cell's soul, said Nolan, who is the Rachford and Carlota Harris Professor. "We can observe not only an immune cell's identity but its state of mind," he said. Nolan holds an equity position in Fluidigm, a company that manufactures cell-cytometry instrumentation and reagents used in the study.

The study recruited 32 otherwise healthy patients, mostly between ages 50 and 80, who were undergoing first-time hip-replacement procedures carried out by Stanford orthopedic surgeons. Blood samples from these patients were drawn one hour before surgery, then at one, 24 and 72 hours post-surgery and again four to six weeks after surgery. The samples were quickly delivered to Nolan's lab, where cytometric analysis of 35 features in and on each sample's roughly half-million constituent cells yielded profiles of the cells' identities along with key activities underway inside them.

Every three days for a full six weeks after surgery, patients filled out questionnaires probing the degree of pain and fatigue they were experiencing and how well their refurbished hip was functioning.

Zeroing in on key predictor

The Stanford team observed what Angst called "a very well-orchestrated, cell-type- and time-specific pattern of immune response to surgery." The pattern consisted of a sequence of coordinated rises and falls in numbers of diverse immune-cell types, along with various changes in activity within each cell type.

"Amazingly, this post-surgical signature showed up in every single patient," Angst said. However, the magnitude of the various increases and decreases in cell numbers and activity varied from one patient to the next.

One particular factor — changes, at one hour versus 24 hours post-surgery, in the activation states of key interacting proteins inside a small set of "first-responder" immune cells — accounted for 40-60 percent of the variation in the timing of these patients' recovery. There was also a notable expansion in the numbers of these front-line cells soon after surgery, but the size of that increase didn't correlate with recovery on an individual basis nearly as strongly as did the changes in activity within the cells.

The cells in question account for only about 1-2 percent of all the white blood cells found in a typical sample of a healthy person's blood, so the changes within them could easily have been missed had a less-thorough detection technology been employed.

The strength of the observed correlation far exceeds the strengths reported in previous studies linking inflammatory responses to clinical recovery. Such studies have typically looked at secreted substances in blood or the trafficking of different kinds of cells at various time points after surgery. But those studies lacked the power to simultaneously observe, for example, which types of immune cells were secreting those blood-borne substances at any given time, or exactly what else those particular cell types were up to at the same time.

Possible Way to Predict Recovery

"If a correlation explains only 2 percent or even 10 percent of the variability in recovery rates, this may clinically not be all that relevant," said Angst. "Our robust correlation may lead to a clinically useful way to predict recovery from surgery."

The researchers believe, but have not yet proven, that the cells whose activity patterns correlated most strongly with patients' recovery trajectories are so-called "myeloid-derived suppressor cells," shown in other studies to damp inflammation. Those cells have been linked to negative outcomes in cancer, where too much activity on their part appears to prevent the body's immune system from attacking tumors.

But in the post-surgery environment, their activity may be just what the doctor ordered.

The Stanford group is now looking to see if they can identify a pre-operation immune signature that predicts the rate of recovery. "If we could predict recovery time before surgery even took place," said Gaudilliere, "we might be able to see who'd benefit from boosting their immune strength beforehand, or from pre-surgery interventions such as physical therapy. It might even help us decide when or if a patient should have surgery."

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by Stanford's Department of Anesthesiology, Pain and Perioperative Medicine; the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine; the European Commission; the U.S. Food and Drug Agency; the Department of Defense; and the National Institutes of Health (grants UL1RR026744, 1R01CA130826, 5U54CA143907, HHSN272200700038C, N01-HV-00242, 41000411217, 1U19AI100627, P01CA034233-22A1, U19AI057229, U54CA149145 and S10RR027582-01).

Other Stanford co-authors of the study are orthopaedic surgery professor and chair William Maloney, MD; orthopaedic surgery professor Stuart Goodman, MD, PhD; orthopaedic surgery associate professor James Huddleston, MD; microbiology and immunology professor Mark Davis, PhD; assistant professor of pathology Sean Bendall, PhD; obstetrics and gynecology assistant professor Wendy Fantl, PhD; research associates Monica Nicolau, PhD, and Edward Ganio, PhD; data analyst Rachel Finck; postdoctoral scholar Robert Bruggner, PhD; research nurse Martha Tingle; social-science research assistant Julian Silva; and biology undergraduate Christine Yeh.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Health Care and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://med.stanford.edu.

Immune activity shortly after surgery holds big clue to recovery rate, Stanford team finds

2014-09-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Stanford scientists use stem cells to learn how common mutation in Asians affects heart health

2014-09-24

Over 500 million people worldwide carry a genetic mutation that disables a common metabolic protein called ALDH2. The mutation, which predominantly occurs in people of East Asian descent, leads to an increased risk of heart disease and poorer outcomes after a heart attack. It also causes facial flushing when carriers drink alcohol.

Now researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have learned for the first time specifically how the mutation affects heart health. They did so by comparing heart muscle cells made from induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS ...

The plus side of population aging

2014-09-24

Around the world, people are living longer and having fewer children, leading to a population that is older, on average, than in the past. On average, life expectancy in developed countries has risen at a pace of three months per year, and fertility has fallen below replacement rate in the majority of Europe and other developed countries.

Most academic discussion of this trend has so far focused on potential problems it creates, including challenges to pension systems, economic growth, and healthcare costs.

But according to a new study published today in the journal PLOS ...

Brain scans reveal 'gray matter' differences in media multitaskers

2014-09-24

Simultaneously using mobile phones, laptops and other media devices could be changing the structure of our brains, according to new University of Sussex research.

A study published today (24 September) reveals that people who frequently use several media devices at the same time have lower grey-matter density in one particular region of the brain compared to those who use just one device occasionally.

The research supports earlier studies showing connections between high media-multitasking activity and poor attention in the face of distractions, along with emotional ...

Colorado's Front Range fire severity not much different than past, say CU study

2014-09-24

The perception that Colorado's Front Range wildfires are becoming increasingly severe does not hold much water scientifically, according to a massive new study led by the University of Colorado Boulder and Humboldt State University in Arcata, Calif.

The study authors, who looked at 1.3 million acres of ponderosa pine and mixed conifer forest from Teller County west of Colorado Springs through Larimer County west and north of Fort Collins, reconstructed the timing and severity of past fires using fire-scarred trees and tree-ring data going back to the 1600s. Only 16 percent ...

New dinosaur from New Mexico has relatives in Alberta

2014-09-24

(Edmonton) A newly discovered armoured dinosaur from New Mexico has close ties to the dinosaurs of Alberta, say University of Alberta paleontologists involved in the research.

From 76 to 66 million years ago, Alberta was home to at least five species of ankylosaurid dinosaurs, the group that includes club-tailed giants like Ankylosaurus. But fewer ankylosaurids are known from the southern parts of North America. The new species, Ziapelta sanjuanensis, was discovered in 2011 in the Bisti/De-na-zin Wilderness area of New Mexico by a team from the New Mexico Museum of Natural ...

A way to kill chemo-resistant ovarian cancer cells: Cut down its protector

2014-09-24

Ottawa, Canada – September 24, 2014 – Ovarian cancer is the most deadly gynecological cancer, claiming the lives of more than 50% of women who are diagnosed with the disease. A study involving Ottawa and Taiwan researchers, published today in the influential Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provides new insight into why ovarian cancer is often resistant to chemotherapy, as well as a potential way to improve its diagnosis and treatment.

It is estimated that 2,700 Canadian women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2014 and that 1,750 Canadian ...

Star Trekish, rafting scientists make bold discovery on Fraser River

2014-09-24

A Simon Fraser University-led team behind a new discovery has "…had the vision to go, like Star Trek, where no one has gone before: to a steep and violent bedrock canyon, with surprising results."

That comment comes from a reviewer about a truly groundbreaking study just published in the journal Nature.

Scientists studying river flow in bedrock canyons for the first time have discovered that previous conceptions of flow and incision in bedrock-rivers are wrong.

SFU geography professor Jeremy Venditti led the team of SFU, University of Ottawa and University of British ...

Bacterial 'communication system' could be used to stop and kill cancer cells, MU study finds

2014-09-24

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Cancer, while always dangerous, truly becomes life-threatening when cancer cells begin to spread to different areas throughout the body. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have discovered that a molecule used as a communication system by bacteria can be manipulated to prevent cancer cells from spreading. Senthil Kumar, an assistant research professor and assistant director of the Comparative Oncology and Epigenetics Laboratory at the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, says this communication system can be used to "tell" cancer cells how to act, ...

Study: Biochar alters water flow to improve sand and clay

2014-09-24

As more gardeners and farmers add ground charcoal, or biochar, to soil to both boost crop yields and counter global climate change, a new study by researchers at Rice University and Colorado College could help settle the debate about one of biochar's biggest benefits -- the seemingly contradictory ability to make clay soils drain faster and sandy soils drain slower.

The study, available online this week in the journal PLOS ONE, offers the first detailed explanation for the hydrological mystery.

"Understanding the controls on water movement through biochar-amended soils ...

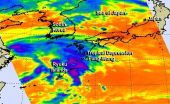

NASA sees the end of post-depression Fung-Wong

2014-09-24

Tropical Depression Fung-Wong looked more like a cold front on infrared satellite imagery from NASA than it did a low pressure area with a circulation.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Depression Fung-Wong on Sept. 23 at 12:23 a.m. EDT. The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard Aqua gathered infrared temperature data on the storm's clouds. The data was false-colored at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California and showed that the storm resembled a frontal system more than a depression. The center of circulation was southwest ...