(Press-News.org) AUDIO:

Editor Karen Carniol interviews Dr. Alla Karpova on her latest Cell paper.

Click here for more information.

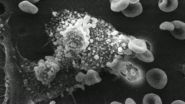

Past experience is usually a reliable guide for making decisions, but in unpredictable and challenging situations, it might make more sense to take risks. A study published by Cell Press September 25th in the journal Cell shows that, in competitive situations, rats abandon their normal tactic of using past experience to make decisions and instead make random choices when their competitor is hard to defeat. This switch in strategy is controlled by a dedicated brain circuit, indicating that the brain can actively disengage from its past experiences and enter a random decision-making mode when it provides a competitive edge. These findings may have implications for human disorders such as depression, in which even ordinary decision-making is viewed as ineffective.

"We discovered that animals can get stuck in a random mode of behavior that in a way resembles learned helplessness, which has been linked to depression and is triggered when repeated efforts prove to be ineffective," said senior study author Alla Karpova of the Janelia Farm Research Campus. "Our findings may shed light on the origins of learned helplessness and the associated impairments in strategic decision-making."

The brain has evolved to optimize behavioral choices by using all available information acquired from past experience. However, when animals encounter new and unpredictable situations, such as a novel environment or prey that moves erratically, it might be more beneficial to instead vary behavior randomly.

To find out if this is indeed the case, Karpova and her team trained rats to stick their nose in one of two ports, or holes in a wall, to potentially receive a sugary Kool-Aid reward. Meanwhile, the animals were monitored by a computer-simulated competitor, which was programmed to analyze past behavior to predict future choices. The rats received juice at the port they selected only if their choice differed from that predicted by the computer. When faced with a weak competitor, the animals made choices based on past experience, as usual. But when a sophisticated competitor used complex algorithms to make strong predictions based on subtle behavioral patterns, the rats actively ignored past experience and instead selected the reward port at random.

To find out whether this shift in strategy is regulated by a specific part of the brain, the authors zeroed in on the anterior cingulate cortex, a brain structure involved in using experience to make decisions. Indeed, when the researchers manipulated the activity of neurons that release a stress hormone called norepinephrine into the anterior cingulate cortex, they were able to reverse the rats' behavioral strategies. Stimulation of these neurons caused rats to abandon the experience-based strategy and behave randomly in situations when this was not expected. By contrast, inhibition of norepinephrine release caused rats to rely on the experience-based strategy even when faced with the challenging competitor.

"The findings suggest that changes in activity in the anterior cingulate cortex could prevent erroneous beliefs from guiding decisions and promote exploratory behavior when environmental rules are uncertain," Karpova says. "But sometimes these changes in neural activity can go too far and become maladaptive, resulting in learned helplessness or even depression. In those cases, suppression of norepinephrine release into the anterior cingulate cortex may serve as an effective therapy to restore strategic decision-making."

INFORMATION:

Cell, Tervo et al.: "Behavioral Variability through Stochastic Choice and its Gating by Anterior Cingulate Cortex."

In the face of uncertainty, the brain chooses randomness as the best strategy

2014-09-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How the brain gains control over Tourette syndrome

2014-09-25

Tourette syndrome is a developmental disorder characterized by involuntary, repetitive, and stereotyped movements or utterances. Now researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 25 have new evidence to explain how those with Tourette syndrome in childhood often manage to gain control over those tics. In individuals with the condition, a portion of the brain involved in planning and executing movements shows an unusual increase compared to the average brain in the production of a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter known as GABA.

The paradoxical ...

Modified vitamin D shows promise as treatment for pancreatic cancer

2014-09-25

VIDEO:

Salk scientists find that a vitamin D-derivative makes tumors vulnerable to chemotherapy.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA—A synthetic derivative of vitamin D was found by Salk Institute researchers to collapse the barrier of cells shielding pancreatic tumors, making this seemingly impenetrable cancer much more susceptible to therapeutic drugs.

The discovery has led to human trials for pancreatic cancer, even in advance of its publication today in the journal ...

How physical exercise protects the brain from stress-induced depression

2014-09-25

Physical exercise has many beneficial effects on human health, including the protection from stress-induced depression. However, until now the mechanisms that mediate this protective effect have been unknown. In a new study in mice, researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden show that exercise training induces changes in skeletal muscle that can purge the blood of a substance that accumulates during stress, and is harmful to the brain. The study is being published in the prestigious journal Cell.

"In neurobiological terms, we actually still don't know what depression ...

Brain chemical potential new hope in controlling Tourette Syndrome tics

2014-09-25

A chemical in the brain plays a vital role in controlling the involuntary movements and vocal tics associated with Tourette Syndrome (TS), a new study has shown.

The research by psychologists at The University of Nottingham, published in the latest edition of the journal Current Biology, could offer a potential new target for the development of more effective treatments to suppress these unwanted symptoms.

The study, led by PhD student Amelia Draper under the supervision of Professor Stephen Jackson, found that higher levels of a neurochemical called GABA in a part ...

Super enhancers in the inflamed endothelium

2014-09-25

Boston, MA – Normally, the lining of blood vessels, or endothelium, when at rest, acts like Teflon, ignoring the many cells and other factors rushing by in the bloodstream. In response to inflammatory signals, as well as other stimuli, endothelial cells change suddenly and dramatically—sending out beacons to attract inflammatory cells, changing their surface so those cells can stick and enter tissues, and initiating a complex cascade of responses essential to fighting infection and dealing with injury. Unfortunately, these same endothelial responses also promote atherosclerosis, ...

Novel compound prevents metastasis of multiple myeloma in mouse studies

2014-09-25

BOSTON –– In an advance against the problem of cancer metastasis, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute scientists have shown that a specially developed compound can impede multiple myeloma from spreading to the bones in mice. The findings, published in the Sept. 25 issue of Cell Reports, suggest the technique can protect human patients, as well, from one of the most deadly aspects of cancer.

The research involves a new approach to the challenge of cancer metastasis, the process by which tumors spread to and colonize distant parts of the body. Whereas research has traditionally ...

Dinosaur family tree gives fresh insight into rapid rise of birds

2014-09-25

The most comprehensive family tree of meat-eating dinosaurs ever created is enabling scientists to discover key details of how birds evolved from them.

The study has shown that the familiar anatomical features of birds – such as feathers, wings and wishbones – all first evolved piecemeal in their dinosaur ancestors over tens of millions of years.

However, once a fully functioning bird body shape was complete, an evolutionary explosion began, causing a rapid increase in the rate at which birds evolved. This led eventually to the thousands of avian species that we know ...

Strategic or random? How the brain chooses

2014-09-25

Many of the choices we make are informed by experiences we've had in the past. But occasionally we're better off abandoning those lessons and exploring a new situation unfettered by past experiences. Scientists at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have shown that the brain can temporarily disconnect information about past experience from decision-making circuits, thereby triggering random behavior.

In the study, rats playing a game for a food reward usually acted strategically, but switched to random behavior when they confronted a particularly ...

New protein players found in key disease-related metabolic pathway

2014-09-25

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (September 25, 2014) – To coordinate their size and growth with current environmental conditions, cells rely on the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway, which senses cellular stresses, growth factors, and the availability of nutrients, such as amino acids and glucose.

For years, Whitehead Institute Member David Sabatini and his lab have been teasing apart the numerous proteins involved in this vital metabolic pathway, in part because mTORC1 function is known to be deregulated in a variety of diseases, including diabetes, epilepsy, ...

Large study pinpoints synapse genes with major roles in severe childhood epilepsies

2014-09-25

An international research team has identified gene mutations causing severe, difficult-to-treat forms of childhood epilepsy. Many of the mutations disrupt functioning in the synapse, the highly dynamic junction at which nerve cells communicate with one another.

"This research represents a paradigm shift in epilepsy research, giving us a new target on which to focus treatment strategies," said pediatric neurologist Dennis Dlugos, M.D., director of the Pediatric Regional Epilepsy Program at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and a study co-author. "There is tremendous ...