(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA – In the second of two papers outlining new gene-therapy approaches to treat a rare disease called MPS I, researchers from Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania examined systemic delivery of a vector to replace the enzyme IDUA, which is deficient in patients with this disorder. The second paper, which is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, describes how an injection of a vector expressing the IDUA enzyme to the liver can prevent most of the systemic manifestations of the disease, including those found in the heart.

The first paper, published in Molecular Therapy, describes the use of an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector to introduce normal IDUA to glial and neuronal cells in the brain and spinal cord in a feline model. The aim of that study was to directly treat the central nervous system manifestations of MPS while the more recent study aims to treat all other manifestations of the disease outside of the nervous system.

This family of diseases comprises about 50 rare inherited disorders marked by defects in the lysosomes, compartments within cells filled with enzymes to digest large molecules. If one of these enzymes is mutated, molecules that would normally be degraded by the lysosome accumulate within the cell and their fragments are not recycled. Many of the MPS disorders can share symptoms, such as speech and hearing problems, hernias, and heart problems. Patient groups estimate that in the United States 1 in 25,000 births will result in some form of MPS. Life expectancy varies significantly for people with MPS I.

The two main treatments for MPS I are bone marrow transplantation and intravenous enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), but these are only marginally effective or clinically impractical, and have significant drawbacks for patient safety and quality of life and do not effectively address some of the most critical clinical symptoms, such as life-threatening cardiac valve impairments.

"Both of these papers are the first proof-of-principle demonstrations for the efficacy and practicality for gene therapies to be translated into the clinic for lysosomal storage diseases," says lead author James M. Wilson, MD, PhD, professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and director of the Penn Gene Therapy Program. "This approach may likely turn out to be better than ERT and compete with or replace ERT. We are especially excited about the use of this approach in treating the many MPS I patients who do not have access to ERT due to cost or inadequate health delivery systems to support repeated protein infusions, such as in China, Eastern Europe, India, and parts of South America."

Patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I), accumulate compounds called glycosaminoglycans in tissues, with resulting diverse clinical symptoms, including neurological, eye, skeletal, and cardiac disease.

Using a naturally occurring feline model of MPS I, the team tested liver-directed gene therapy via a single intravenous infusion as a means of establishing long-term systemic IDUA presence throughout the body.

The team treated four MPS I cats at three to five months of age with an AAV serotype 8 vector expressing feline IDUA. "We observed sustained serum enzyme activity for six months at approximately 30 percent of normal levels in one animal and in excess of normal levels in the other three animals," says Wilson.

Remarkably, treated animals not only demonstrated reductions in glycosaminoglycans storage in most tissues, but most also exhibited complete resolution of aortic valve lesions, an effect which has not been previously observed in this animal model or in MPS I patients treated with current therapies.

Critical to the evaluation of these novel therapies is the feline model of MPS I, which was provided through coauthor Mark E. Haskins, School of Veterinary Medicine at Penn. Haskins and his colleagues maintain a variety of canine and feline models of human genetic diseases that have been instrumental in establishing proof of concept for a number of novel therapeutics, including the current enzyme replacement therapy.

The Penn team says that these findings point to clinically meaningful benefits of the robust enzyme expression achieved with liver gene transfer that may extend the economic and quality of life advantages over lifelong enzyme infusion.

INFORMATION:

Other coauthors are Christian Hinderer, Peter Bell, Qiang Wang, Brittney L. Gurda, Jean Pierre Louboutin, Yanqing Zhu, Jessica Bagel, Patricia O'Donnell, Tracey Sikora, Therese Ruane, and Ping Wang.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants P40-OD010939 and DK25759 and REGENXBIO, a Washington, D.C.-based biotech firm that holds licenses in technology used in this study.

Editor's Note:

Wilson is an advisor to REGENXBIO, and is a founder of, holds equity in, and receives grants from REGENXBIO. REGENXBIO holds license and option rights to technologies developed by Wilson at the University of Pennsylvania; in addition, Wilson is a founder, advisor and consultant to several other biopharmaceutical companies and is an inventor on patents licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies, including REGENXBIO.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $392 million awarded in the 2013 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2013, Penn Medicine provided $814 million to benefit our community.

Liver gene therapy corrects heart symptoms in model of rare enzyme disorder

2014-09-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Higher gun ownership rates linked to increase in non-stranger homicide, BU study finds

2014-09-29

A new study led by a Boston University School of Public Health researcher has found that states with higher estimated rates of gun ownership experience a higher incidence of non-stranger firearms homicides – disputing the claim that gun ownership deters violent crime, its authors say.

The study, published in the American Journal of Public Health, found no significant relationship between levels of gun ownership and rates of stranger-on-stranger homicide. But it did find that higher levels of gun ownership were associated with increases in non-stranger homicide rates, ...

Study holds hope of a treatment for deadly genetic disease, MPS IIIB

2014-09-29

LOS ANGELES – (Sept. 29, 2014) –MPS IIIB is a devastating and currently untreatable disease that causes progressive damage to the brain, leading to profound intellectual disability, dementia and death -- often before reaching adulthood.

Officially known as mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB or Sanfilippo Syndrome type B, the disease causes the accumulation of waste products in the cells, leading to progressive damage to the brain. Patients with MPS IIIB lack a vital enzyme that is needed to break down long chains of sugars, known as mucopolysaccharides, leading these to ...

Feeling fatigued while driving? Don't reach for your iPod

2014-09-29

Research has shown that drinking caffeinated beverages and listening to music are two popular fatigue-fighting measures that drivers take, but very few studies have tested the usefulness of those measures. New research to be presented at the HFES 2014 Annual Meeting in Chicago evaluates which method, if either, can successfully combat driver fatigue.

In their paper titled "Comparison of Caffeine and Music as Fatigue Countermeasures in Simulated Driving Tasks," human factors/ergonomics researchers ShiXu Liu, Shengji Yao, and Allan Spence designed a simulated driving study ...

New way to detox? 'Gold of Pleasure' oilseed boosts liver detoxification enzymes

2014-09-29

URBANA, Ill. – University of Illinois scientists have found compounds that boost liver detoxification enzymes nearly fivefold, and they've found them in a pretty unlikely place—the crushed seeds left after oil extraction from an oilseed crop used in jet fuel.

"The bioactive compounds in Camelina sativa seed, also known as Gold of Pleasure, are a mixture of phytochemicals that work together synergistically far better than they do alone. The seed meal is a promising nutritional supplement because its bioactive ingredients increase the liver's ability to clear foreign chemicals ...

University of Alberta researchers explain 38-year-old mystery of the heart

2014-09-29

In a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, researchers at the University of Alberta's Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry have explained how the function of a key protein in the heart changes in heart failure.

Heart disease is the number-one killer in the developed world. The end stage of heart disease is heart failure, in which the heart cannot pump enough blood to satisfy the body's needs. Patients become progressively short of breath as the condition worsens, and they also begin to accumulate fluid in the legs and lungs, making it ...

Good working relationships between clients, bankers can reduce defaults

2014-09-29

You've probably seen advertising campaigns in which banks describe how much their customer relationships matter to them. While such messaging might have been cooked up at an ad agency, it turns out there is some truth underlying these slogans.

As a newly published study co-authored by an MIT professor shows, strong working relationships between bankers and clients reduce the likelihood of loan delinquencies and defaults, at least in the context of an emerging economy.

Using propriety data from a large bank in Chile, the study finds that when loan officers go on leave, ...

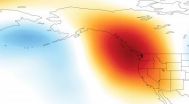

Causes of California drought linked to climate change

2014-09-29

The atmospheric conditions associated with the unprecedented drought currently afflicting California are "very likely" linked to human-caused climate change, Stanford scientists say.

In a new study, a team led by Stanford climate scientist Noah Diffenbaugh used a novel combination of computer simulations and statistical techniques to show that a persistent region of high atmospheric pressure hovering over the Pacific Ocean that diverted storms away from California was much more likely to form in the presence of modern greenhouse gas concentrations.

The research, published ...

Decision to reintroduce aprotinin in cardiac surgery may put patients at risk

2014-09-29

Cardiac surgery patients may be at risk because of the decision by Health Canada and the European Medicines Agency to reintroduce the use of aprotinin after its withdrawal from the worldwide market in 2007, assert the authors of a previous major trial that found a substantially increased risk of death associated with the drug. In an analysis in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal), the authors refute three major criticisms of the trial made by the regulatory bodies.

Aprotinin, used to control bleeding in cardiac surgery, was withdrawn worldwide in 2007 after the ...

Revolutionary hamstring tester will keep more players on the field

2014-09-29

Elite sporting stars can assess and reduce their risk of a hamstring injury thanks to a breakthrough made by QUT researchers.

The discovery could be worth a fortune to football codes, with hamstring strain injuries accounting for most non-contact injuries in Australian rules football, football and rugby union, as well as track events like sprinting.

Using an innovative field device, a research team led by Dr Anthony Shield, from QUT's School - Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, and former QUT PhD student, Dr David Opar, now at the Australian Catholic University, measured ...

Drug for kidney injury after cardiac surgery does not reduce need for dialysis

2014-09-29

Among patients with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery, infusion with the antihypertensive agent fenoldopam, compared with placebo, did not reduce the need for renal replacement therapy (dialysis) or risk of death at 30 days, but was associated with an increased rate of abnormally low blood pressure, according to a study published in JAMA. The study is being posted early online to coincide with its presentation at the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine annual congress.

More than 1 million patients undergo cardiac surgery every year in the United States ...