(Press-News.org) London, United Kingdom, October 2, 2014 – Despite decades of research, scientists have yet to pinpoint the exact cause of nodding syndrome (NS), a disabling disease affecting African children. A new report suggests that blackflies infected with the parasite Onchocerca volvulus may be capable of passing on a secondary pathogen that is to blame for the spread of the disease. New research is presented in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Concentrated in South Sudan, Northern Uganda, and Tanzania, NS is a debilitating and deadly disease that affects young children between the ages of 5 and 15. When present, the first indication of the disease is an involuntary nodding of the head, followed by epileptic seizures. The condition can cause cognitive deterioration, stunted growth, and in some cases, death.

There is an acknowledged link between NS and onchocerciasis, an infection by a small worm commonly known as river blindness. NS is only present in areas where onchocerciasis is endemic and other studies have shown that there is a high rate of onchocerciasis infections in children with NS. Despite this apparent connection, investigators have been unable to link the two concretely. Onchocerca volvulus—the parasite that causes river blindness--has not been shown to affect brain function, which would be required if the parasite were also directly responsible for causing NS.

This new study from the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium proposes that along with transmitting the Onchocerca volvulus parasite, blackflies are also passing along a second pathogen that is responsible for NS. "We hypothesize that blackflies infected with Onchocerca volvulus microfilariae may also transmit another pathogen," notes lead investigator Robert Colebunders, MD, PhD, who is head of the HIV/STD Unit, Department of Clinical Sciences at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, and Professor of Infectious Diseases at the University of Antwerp. "This may be a novel neurotropic virus or an endosymbiont of the microfilariae, which causes not only NS, but also epilepsy without nodding."

The hypothesis draws on other research that shows that parasites and viruses can have a symbiotic relationship, allowing insects to pass on diseases they would not normally be able to transmit. "Many laboratory studies have shown that arboviral transmission is enhanced in mosquitoes and other blood feeding flies that concurrently ingest microfilariae, and the same could be true for blackflies," explains Dr. Colebunders. "The biting midge, Culicoides nubeculosus, became infectious after ingesting blue tongue virus and Onchocerca cervicalis microfilariae, but not after ingesting the virus alone."

There are still many key questions surrounding the spread of NS, but this new theory attempts to deliver possible answers. For example, as to why NS epidemics seem to come and go, the study asserts that indigenous populations may become immune to the NS pathogen over time, but that when forced migration moves a non-immune population into an area with a large number of blackflies, NS cases erupt. "Population displacement resulting from civil conflict has preceded NS outbreaks in both northern Uganda and South Sudan," Dr. Colebunders states.

The study also illustrates how aerial spraying of insecticides and ground application of larvicides to rivers—two key actions to control the blackfly population—have affected the rates of NS in locations like Northern Uganda. When steps were taken to reduce the blackfly population around known breeding grounds in 2012, it was followed by a decrease in cases of NS and no new cases were reported in 2013. Northern Uganda also began a comprehensive ivermectin (the anti-parasitic drug used to prevent river blindness) distribution program in 2012, which may also account in part for the drop in NS cases.

Dr. Colebunders suggests several courses of action based on the new theory, including collecting more precise incidence data on NS, epilepsy, and onchocerciasis in relation to blackfly distribution; continuing and increasing the systematic use of larvicides to control the blackfly population; and improving ivermectin coverage and increasing the frequency of its administration, as it appears it may limit the blackfly's ability to transmit the novel NS pathogen.

"The burden of disease may be considerable, as the 'NS pathogen' may also cause epilepsy without nodding," concludes Dr. Colebunders. "The planning of a clinical trial to evaluate these strategies, either alone or in combination, should be considered."

INFORMATION:

A new study published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on October 2 could rewrite the story of ape and human brain evolution. While the neocortex of the brain has been called "the crowning achievement of evolution and the biological substrate of human mental prowess," newly reported evolutionary rate comparisons show that the cerebellum expanded up to six times faster than anticipated throughout the evolution of apes, including humans.

The findings suggest that technical intelligence was likely at least as important as social intelligence in human cognitive ...

The more curious we are about a topic, the easier it is to learn information about that topic. New research publishing online October 2 in the Cell Press journal Neuron provides insights into what happens in our brains when curiosity is piqued. The findings could help scientists find ways to enhance overall learning and memory in both healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions.

"Our findings potentially have far-reaching implications for the public because they reveal insights into how a form of intrinsic motivation—curiosity—affects memory. These findings ...

This release is available in Japanese.

A University of Tokyo research group has discovered that AIM (Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophage), a protein that plays a preventive role in obesity progression, can also prevent tumor development in mice liver cells. This discovery may lead to a therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer and the third most common cause of cancer deaths.

Professor Toru Miyazaki's group at the Laboratory of Molecular Biomedicine from Pathogenesis, in the Faculty of Medicine has shown that AIM (also known ...

LA JOLLA, CA—October 2, 2014—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that an enzyme best known for its fundamental role in building proteins has a second major function: to protect DNA during times of cellular stress.

The finding is remarkable on a basic science level but also points the way to possible therapeutic applications. Strategies that enhance the DNA-protection function of the enzyme, TyrRS, could help protect people from radiation injuries as well as from hereditary defects in DNA repair systems.

"We overexpressed TyrRS in zebrafish ...

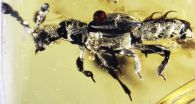

Scientists have uncovered the fossil of a 52-million-year old beetle that likely was able to live alongside ants—preying on their eggs and usurping resources—within the comfort of their nest. The fossil, encased in a piece of amber from India, is the oldest-known example of this kind of social parasitism, known as "myrmecophily." Published today in the journal Current Biology, the research also shows that the diversification of these stealth beetles, which infiltrate ant nests around the world today, correlates with the ecological rise of modern ants.

"Although ants ...

Our immune system must distinguish between self and foreign and in order to fight infections without damaging the body's own cells at the same time. The immune system is loyal to cells in the body, but how this works is not fully understood. Researchers in the Departments of Biomedicine and Nephrology at the University Hospital and the University of Basel have discovered that the immune system uses a molecular biological clock to target intolerant T cells during their maturation process. These recent findings have been reported in the scientific journal Cell.

A functioning ...

It's an early lesson in genetics: we get half our DNA from Mom, half from Dad.

But that straightforward explanation does not account for a process that sometimes occurs when cells divide. Called gene conversion, the copy of a gene from Mom can replace the one from Dad, or vice versa, making the two copies identical.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, University of Pennsylvania researchers Joseph Lachance and Sarah A. Tishkoff investigated this process in the context of the evolution of human populations. They found that a bias toward ...

Scientists love acronyms.

In the quest to solve cancer's mysteries, they come in handy when describing tongue-twisting processes and pathways that somehow allow tumors to form and thrive. Two examples are ERK (extracellular-signal-related kinase) and JNK (c-June N-Terminal Kinase), enzymes that may offer unexpected solutions for treating some endometrial and colon cancers.

A study led by Gordon Mills, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chair of Systems Biology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center with Lydia Cheung, Ph.D. as the first author, points to cellular ...

Television sitcoms in which characters make jokes at someone else's expense are no laughing matter for older adults, according to a University of Akron researcher.

Jennifer Tehan Stanley, an assistant professor of psychology, studied how young, middle-aged and older adults reacted to so-called "aggressive humor"—the kind that is a staple on shows like The Office.

By showing clips from The Office and other sitcoms (Golden Girls, Mr. Bean, Curb Your Enthusiasm) to adults of varying ages, she and colleagues at two other universities found that young and middle-aged adults ...

AUDIO:

Atika Khurana, assistant professor in the University of Oregon's Department of Counseling Psychology and Human Services, provides a short summary and the implications of a study that looked at the...

Click here for more information.

EUGENE, Ore. -- Oct. 2, 2014 -- Adolescents with strong working memory are better equipped to escape early drug experimentation without progressing into substance abuse issues, says a University of Oregon researcher.

Most important in the picture ...