(Press-News.org) This news release is available in French.

Montreal October 2, 2014 – Treatment approaches to reduce the risk of bone complications (metastasis) associated with breast cancer may be one step closer to becoming a reality. According to a study led by a team at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC), findings show that medication used to treat bone deterioration in post-menopausal women may also slow skeletal metastasis caused from breast cancer. This study, published in this month's issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI), is among the first to link bisphosphonate (a common osteoporosis medication) use with improved survival in women with breast cancer.

"Skeletal metastases develop in up to 70 percent of women who die from breast cancer," says study co-lead author, Dr. Richard Kremer, director of the Bone and Mineral Unit at the MUHC and a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at McGill University. "This causes considerable suffering and is life-threatening. Preventing this could translate into saving a significant number of lives."

Reduction of metastatic risk by half

Dr. Kremer and co-lead author, Dr. Nancy Mayo, worked with colleagues to evaluate data from more than 21,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer. The relationship between use of oral bisphosphonates and development of bone metastases after diagnosis with breast cancer was evaluated in two groups of women: those with early stage, localized, cancer and those whose cancer had spread to lymph nodes. Their findings showed that women with early stage breast cancer who had taken oral bisphosphonates, either before or after diagnosis of their cancer, had a reduced risk of bone metastasis. In addition, their study showed that women with later stage cancer, who took oral bisphosphonates post-diagnosis, also had a significantly reduced risk of bone metastasis.

The researchers also established a dose-response relationship with oral bisphophonate use in women with local disease: longer time spent on bisphophonate medication resulted in a greater reduction of bone metastases.

"Our study is novel in that it mainly involved women who were post-menopausal and in whom bone-turnover is high due to osteoporosis," says Dr. Richard Kremer who is also an RI-MUHC researcher. "We believe that this process results in an environment that is favorable for tumour cell growth and consequent metastasis. We know that bisphosphonates work by slowing down this bone-turnover. This will, in turn, make it harder for tumour cells to establish in the bone and may explain why we saw such a decline in metastasis."

Clinical studies needed

"An association between bisphophonate use and improved survival was also observed and this merits further investigation," Dr. Mayo, RI-MUHC researcher and James McGill professor in the Faculty of Medicine, School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill. "Ours was an epidemiological study, involving a large number of women strengthening the importance of the findings. However, clinical interventional studies are needed before the results can be translated into standard clinical practice and guidelines."

INFORMATION:

About the study:

This research was made possible thanks to funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Initiative, the Quebec Network for Research on Drug Use , the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) and the Susan G. Komen Foundation

The paper Effects of oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis on development of skeletal metastases in women with breast cancer: Results from a pharmaco-epidemiological study was co-authored by Richard Kremer, Department of Medicine, McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), Montreal, QC; Bruno Gagnon, Division of Clinical Epidemiology, MUHC, Montreal, QC and Centre de Recherche sur le Cancer, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC; Ari N. Meguerditchian, Department of Surgery, MUHC, Montreal, QC; Lyne Nadeau, Division of Clinical Epidemiology, MUHC, Montreal, QC; and Nancy Mayo, Department of Medicine and Division of Clinical Epidemiology, MUHC, Montreal, QC.

Related links:

Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI): jnci.oxfordjournals.org

McGill University Health Centre (MUHC): muhc.ca

Research Institute of the MUHC: rimuhc.ca

McGill University: mcgill.ca

Media contact:

Julie Robert

Public Affairs & Strategic planning

McGill University Health Centre

julie.robert@muhc.mcgill.ca

514 934-1934 ext. 71381

facebook.com/cusm.muhc|http://www.muhc.ca

National Institutes of Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Canadian Institutes of Health Research New research by scientists at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UM SOM) and the Ottawa Heart Institute has uncovered a new pathway by which the brain uses an unusual steroid to control blood pressure. The study, which also suggests new approaches for treating high blood pressure and heart failure, appears today in the journal Public Library of Science (PLOS) One.

"This research gives us an entirely new way of understanding how the brain and the ...

Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have identified a biomarker living next door to the KLK3 gene that can predict which GS7 prostate cancer patients will have a more aggressive form of cancer.

The results reported in the journal of Clinical Cancer Research, a publication of the American Association of Cancer Research, indicate the KLK3 gene – a gene on chromosome 19 responsible for encoding the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) – is not only associated with prostate cancer aggression, but a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on it is more ...

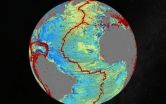

Scientists have created a new map of the world's seafloor, offering a more vivid picture of the structures that make up the deepest, least-explored parts of the ocean.

The feat was accomplished by accessing two untapped streams of satellite data.

Thousands of previously uncharted mountains rising from the seafloor, called seamounts, have emerged through the map, along with new clues about the formation of the continents.

Combined with existing data and improved remote sensing instruments, the map, described today in the journal Science, gives scientists new tools ...

Zoonosis—transmission of infections from other vertebrates to humans—causes regular and sometimes serious disease outbreaks. Bats are a well-known vertebrate reservoir of viruses like rabies and Ebola. Recent discovery of sequences in bats that are resemble influenza virus genes raised the question of whether bat flu viruses exist and could pose a threat to humans. A study published on October 2nd in PLOS Pathogens addresses this question based on detailed molecular and virological characterization.

Because no infectious virus particles were isolated from the bat samples ...

Scientists at the University of California, Santa Cruz, using a new wildlife tracking collar they developed, were able to continuously monitor the movements of mountain lions in the wild and determine how much energy the big cats use to stalk, pounce, and overpower their prey.

The research team's findings, published October 3 in Science, help explain why most cats use a "stalk and pounce" hunting strategy. The new "SMART" wildlife collar--equipped with GPS, accelerometers, and other high-tech features--tells researchers not just where an animal is but what it is doing ...

VIDEO:

This is a video interview with Jens Nielsen.

With a simple mutation, yeast can grow in higher than normal temperatures. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology demonstrate this in an article...

Click here for more information.

With a simple mutation, yeast can grow in higher than normal temperatures. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology demonstrate this in an article to be published in the scientific journal Science. The findings may result in ethanol ...

Wild cheetah populations have declined precipitously in the past century: from an estimated 100,000 in 1900 to only around 10,000 today. A new study from researchers in Europe, South Africa and at North Carolina State University suggests that the energy cheetahs spend looking for prey, rather than their high-speed hunting tactics or food stolen by other predators, may be to blame for their dwindling numbers.

Cheetahs are high-speed hunters, but are not the strongest predators in their ecosystems. Often, hyenas and lions will take advantage of this, stealing the cheetah's ...

VIDEO:

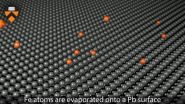

Princeton University researchers first deposited iron atoms onto a lead surface to create an atomically thin wire. They then used a scanning-tunneling microscope to create a magnetic field and to...

Click here for more information.

Princeton University scientists have observed an exotic particle that behaves simultaneously like matter and antimatter, a feat of math and engineering that could yield powerful computers based on quantum mechanics.

Using a two-story-tall microscope ...

The HIV pandemic with us today is almost certain to have begun its global spread from Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), according to a new study.

An international team, led by Oxford University and University of Leuven scientists, has reconstructed the genetic history of the HIV-1 group M pandemic, the event that saw HIV spread across the African continent and around the world, and concluded that it originated in Kinshasa. The team's analysis suggests that the common ancestor of group M is highly likely to have emerged in Kinshasa around ...

Accessing two previously untapped streams of satellite data, scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and their colleagues have created a new map of the world's seafloor, creating a much more vivid picture of the structures that make up the deepest, least-explored parts of the ocean. Thousands of previously uncharted mountains rising from the seafloor and new clues about the formation of the continents have emerged through the new map, which is twice as accurate as the previous version produced nearly 20 years ago.

Developed using a scientific ...