(Press-News.org) When kids say "the darnedest things," it's often in response to something they heard or saw. This sponge-like learning starts at birth, as infants begin to decipher the social world surrounding them long before they can speak.

Now researchers at the University of Washington have found that children as young as 15 months can detect anger when watching other people's social interactions and then use that emotional information to guide their own behavior.

The study, published in the October/November issue of the journal, Cognitive Development, is the first evidence that younger toddlers are capable of using multiple cues from emotions and vision to understand the motivations of the people around them.

"At 15 months of age, children are trying to understand their social world and how people will react," said lead author Betty Repacholi, a faculty researcher at UW's Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences and an associate professor of psychology. "In this study we found that toddlers who aren't yet speaking can use visual and social cues to understand other people – that's sophisticated cognitive skills for 15-month-olds."

The findings also linked the toddlers' impulsive tendencies with their tendency to ignore other people's anger, suggesting an early indicator for children who may become less willing to abide by rules.

"Self-control ranks as one of the single most important skills that children acquire in the first three years of life," said co-author Andrew Meltzoff, co-director of the institute. "We measured the origins of self-control and found that most of the toddlers were able to regulate their behavior. But we also discovered huge individual variability, which we think will predict differences in children as they grow up and may even predict important aspects of school readiness."

In the experiment, 150 toddlers at 15 months of age – an even mix of boys and girls – sat on their parents' laps and watched as an experimenter sat at a table across from them and demonstrated how to use a few different toys.

Each toy had movable parts that made sounds, such as a strand of plastic beads that made a rattle when dropped into a plastic cup and a small box that "buzzed" when pressed with a wooden stick. The children watched eagerly – leaning forward and sometimes pointing enthusiastically.

Then a second person, referred to as the "emoter," entered the room and sat down on a chair near the table. The experimenter repeated the demonstration and the emoter complained in an angry voice, calling the experimenter's actions with the toys "aggravating" and "annoying."

After witnessing the simulated argument, the children had a chance to play with the toys, but under slightly different circumstances. For some, the emoter left the room or turned her back so she couldn't see what the child was doing. In these situations, toddlers eagerly grabbed the toy and copied the actions they had seen in the demonstration.

In other groups, the angered emoter maintained a neutral facial expression while either watching the child or looking at a magazine. Most toddlers in these groups hesitated before touching the toy, waiting about four seconds on average. And when they finally did reach out, the children were less likely to imitate the action the experimenter had demonstrated.

Here's a video of the experimental procedure: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FC4qRD1vn8.

The study didn't factor in how much previous conflict children had seen at home or elsewhere, such as arguing parents or violent television shows. But Repacholi speculated that an emotionally charged home environment could make some children desensitized to anger, or others could become hypersensitive to it and overreact.

The researchers also wondered if the children's temperament played a role. They had parents fill out the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire, which uses questions like "How long does your child stop and think before making decisions?" to measure impulsivity.

The higher the score for impulsivity, the researchers found, the more likely the toddlers were to perform the forbidden actions when the anger-prone adult was watching them.

Repacholi and Meltzoff are doing a follow-up study with the toddlers, who are now school-aged, to see if their behaviors as 15-month-olds predicts their later ability to control their own behavior.

"Ultimately, we want kids who are well regulated, who can use multiple cues from others to help decide what they should and shouldn't do," Repacholi said.

INFORMATION:

Other UW co-authors are Hillary Rowe and Tamara Spiewak Toub. The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

For more information, contact Meltzoff at 206-685-2045 or meltzoff@uw.edu or Repacholi at 206-543-8141 or bettyr@uw.edu.

LAWRENCE — Scientists have been laboring to detect cancer and a host of other diseases in people using promising new biomarkers called "exosomes." Indeed, Popular Science magazine named exosome-based cancer diagnostics one of the 20 breakthroughs that will shape the world this year. Exosomes could lead to less invasive, earlier detection of cancer, and sharply boost patients' odds of survival.

"Exosomes are minuscule membrane vesicles — or sacs — released from most, if not all, cell types, including cancer cells," said Yong Zeng, assistant professor ...

You're obese, at risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and so motivated to improve your diet that you've enrolled in an intensive behavioral program. But if you need to travel more than a short distance to a store that offers a good selection of healthy food, your success may be limited.

A new study from UMass Medical School and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health finds that not having close access to healthy foods can deter even the most motivated dieters from improving their diet, suggesting that easy access to healthy food is as important as personal ...

Imagine attempting to trace your genetic history using only information from your mother's side. That's what scientists studying the evolution of the red fox had been doing for decades.

Now, University of California, Davis, researchers have for the first time investigated ancestry across the red fox genome, including the Y chromosome, or paternal line. The data, compiled for over 1,000 individuals from all over the world, expose some surprises about the origins, journey and evolution of the red fox, the world's most widely distributed land carnivore.

"The genome and ...

Typhoon Vongfong strengthened into a Super typhoon on Tuesday, October 7 as NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead.

On Oct. 7 at 0429 UTC (12:29 a.m. EDT) the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder called AIRS that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured cloud top temperature data on Super typhoon Vongfong. AIRS data very strong thunderstorms circling Vongfong's clear 27 nautical-mile wide eye. Those cloud top temperatures were colder than -62F/-53C indicating that they were high in the troposphere and capable of generating heavy rainfall. The bands of thunderstorms circling ...

New Swedish research shows that plasmids containing genes that confer resistance to antibiotics can be enriched by very low concentrations of antibiotics and heavy metals. These results strengthen the suspicion that the antibiotic residues and heavy metals (such as arsenic, silver and copper) that are spread in the environment are contributing to the problems of resistance. These findings have now been published in the highly regarded journal mBio.

Antibiotic resistance is a growing medical problem that threatens human health worldwide. Why and how these resistant bacteria ...

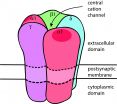

PHILADELPHIA — Nearly 60,000 Americans suffer from myasthenia gravis (MG), a non-inherited autoimmune form of muscle weakness. The disease has no cure, and the primary treatments are nonspecific immunosuppressants and inhibitors of the enzyme cholinesterase.

Now, a pair of researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have developed a fast-acting "vaccine" that can reverse the course of the disease in rats, and, they hope, in humans. Jon Lindstrom, PhD, a Trustee Professor in the department of Neuroscience led the study, published ...

A new review of the way health care professionals emphasise weight to define health and wellbeing suggests the approach could be harmful to patients.

Author of the review article, Dr Rachel Calogero of the School of Psychology at the University of Kent, together with experts from other institutions and organisations, recommends that this approach, known as 'weight-normative', is replaced by health care professionals, public health officials and policy-makers with a 'weight-inclusive' approach.

Weight-inclusive approaches, such as the Health At Every Size initiative, ...

Hamilton, ON (October 7, 2014) – Hospital visitors and staff are greeted with hand sanitizer dispensers in the lobby, by the elevators and outside rooms as reminders to wash their hands to stop infections, but just how clean are patients' hands?

A study led by McMaster University researcher Dr. Jocelyn Srigley has found that hospitalized patients wash their hands infrequently. They wash about 30 per cent of the time while in the washroom, 40 per cent during meal times, and only three per cent of the time when using the kitchens on their units. Hand hygiene rates ...

LONDON, ON – New research shows probiotic yogurt can reduce the uptake of certain heavy metals and environmental toxins by up to 78% in pregnant women. Led by Scientists at Lawson Health Research Institute's Canadian Centre for Human Microbiome and Probiotic Research, this study provides the first clinical evidence that a probiotic yogurt can be used to reduce the deadly health risks associated with mercury and arsenic.

Environmental toxins like mercury and arsenic are commonly found in drinking water and food products, especially fish. These contaminants are particularly ...

Two years ago, Prof. Eshel Ben-Jacob of Tel Aviv University's School of Physics and Astronomy and Rice University's Center for Theoretical Biological Physics made the startling discovery that cancer, like an enemy hacker in cyberspace, targets the body's communication network to inflict widespread damage on the entire system. Cancer, he found, possessed special traits for cooperative behavior and used intricate communication to distribute tasks, share resources, and make decisions.

In research published in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of ...