Special UO microscope captures defects in nanotubes

University of Oregon chemists provide a detailed view of traps that disrupt energy flow, possibly pointing toward improved charge-carrying devices

2014-10-21

(Press-News.org) EUGENE, Ore. -- Oct. 21, 2014 -- University of Oregon chemists have devised a way to see the internal structures of electronic waves trapped in carbon nanotubes by external electrostatic charges.

Carbon nanotubes have been touted as exceptional materials with unique properties that allow for extremely efficient charge and energy transport, with the potential to open the way for new, more efficient types of electronic and photovoltaic devices. However, these traps, or defects, in ultra-thin nanotubes can compromise their effectiveness.

Using a specially built microscope capable of imaging matter at the atomic scale, the researchers were able to visualize traps, which can adversely affect the flow of electrons and elementary energy packets called excitons.

The study, said George V. Nazin, a professor of physical chemistry, modeled the behavior often observed in carbon nanotube-based electronic devices, where electronic traps are induced by stochastic external charges in the immediate vicinity of the nanotubes. The external charges attract and trap electrons propagating through nanotubes.

"Our visualization should be useful for the development of a more accurate picture of electron propagation through nanotubes in real-world applications, where nanotubes are always subjected to external perturbations that potentially may lead to the creation of these traps," he said.

The research, detailed in a paper in the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, was done with an ultra-high vacuum scanning tunneling microscope coupled to a closed-cycle cryostat -- a novel device built for use in Nazin's lab. The cryostat allowed Nazin and his co-authors Dmitry A. Kislitsyn and Jason D. Hackley, both doctoral students, to lower the temperature to 20 Kelvin to freeze all nanoscale motion, and visualize the internal structures of nanoscale objects.

The device captured the internal structure of electronic waves trapped in short sections, just several nanometers long, of nanotubes partially suspended above an atomically flat gold surface. The properties of the waves, to a large extent, Nazin said, determine electron transmission through such electronic traps. The propagating electrons have to be in resonance with the localized waves for efficient electronic transmission to occur.

"Amazingly, by finely tuning the energies of propagating electrons, we found that, in addition to these resonance transmission channels, other resonances also are possible, with energies matching those of specific vibrations in carbon nanotubes," he said. "These new transmission channels correspond to 'vibronic' resonances, where trapped electronic waves excite vibrations of carbon atoms forming the electronic trap."

The microscope the team used is detailed separately in a freely available paper (High-stability cryogenic scanning tunneling microscope based on a closed-cycle cryostat) placed online Oct. 7 by the journal Review of Scientific Instruments.

INFORMATION:

The National Science Foundation (grant DMR-0960211) and a grant from the Oregon Nanoscience and Microtechnologies Institute (ONAMI) supported the construction of the microscope used in the project.

Nazin's co-authors on the paper detailing the microscope are Hackley, Kislitsyn, former UO doctoral student Daniel K. Beaman, now at Intel Corp. in Hillsboro, Oregon, and Stefan Ulrich of RHK Technologies Inc. in Troy, Michigan.

Source: George Nazin, assistant professor of physical chemistry, 541-346-2017, gnazin@uoregon.edu

Note: The University of Oregon is equipped with an on-campus television studio with a point-of-origin Vyvx connection, which provides broadcast-quality video to networks worldwide via fiber optic network. In addition, there is video access to satellite uplink, and audio access to an ISDN codec for broadcast-quality radio interviews.

Links:

About Nazin: http://chemistry.uoregon.edu/profile/gnazin/

Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry: http://chemistry.uoregon.edu/

JPCL paper: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jz5015967

Paper on microscope: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/rsi/85/10/10.1063/1.4897139

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-10-21

MADISON, Wis. — As Dane County begins the long slide into winter and the days become frostier this fall, three spots stake their claim as the chilliest in the area.

One is a cornfield in a broad valley and two are wetlands. In contrast, the isthmus makes an island — an urban heat island.

In a new study published this month in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers highlight the urban heat island effect in Madison: The city's concentrated asphalt, brick and concrete lead to higher temperatures than ...

2014-10-21

BETHESDA, MD – Age-related loss of the Y chromosome (LOY) from blood cells, a frequent occurrence among elderly men, is associated with elevated risk of various cancers and earlier death, according to research presented at the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) 2014 Annual Meeting in San Diego.

This finding could help explain why men tend to have a shorter life span and higher rates of sex-unspecific cancers than women, who do not have a Y chromosome, said Lars Forsberg, PhD, lead author of the study and a geneticist at Uppsala University in Sweden.

LOY, ...

2014-10-21

(Philadelphia, PA) – Chest pain doesn't necessarily come from the heart. An estimated 200,000 Americans each year experience non-cardiac chest pain, which in addition to pain can involve painful swallowing, discomfort and anxiety. Non-cardiac chest pain can be frightening for patients and result in visits to the emergency room because the painful symptoms, while often originating in the esophagus, can mimic a heart attack. Current treatment — which includes pain modulators such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) — has a partial 40 to 50 ...

2014-10-21

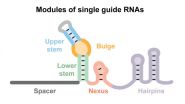

Customized genome editing – the ability to edit desired DNA sequences to add, delete, activate or suppress specific genes – has major potential for application in medicine, biotechnology, food and agriculture.

Now, in a paper published in Molecular Cell, North Carolina State University researchers and colleagues examine six key molecular elements that help drive this genome editing system, which is known as CRISPR-Cas.

NC State's Dr. Rodolphe Barrangou, an associate professor of food, bioprocessing and nutrition sciences, and Dr. Chase Beisel, an assistant ...

2014-10-21

A longstanding question among scientists is whether evolution is predictable. A team of researchers from UC Santa Barbara may have found a preliminary answer. The genetic underpinnings of complex traits in cephalopods may in fact be predictable because they evolved in the same way in two distinct species of squid.

Last, year, UCSB professor Todd Oakley and then-Ph.D. student Sabrina Pankey profiled bioluminescent organs in two species of squid and found that while they evolved separately, they did so in a remarkably similar manner. Their findings are published today in ...

2014-10-21

Research in recent years has shown that people associate specific facial traits with an individual's personality. For instance, people consistently rate faces that appear more feminine or that naturally appear happy as looking more trustworthy. In addition to trustworthiness, people also consistently associate competence, dominance, and friendliness with specific facial traits. According to an article published by Cell Press on October 21st in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, people rely on these subtle and arbitrary facial traits to make important decisions, from voting for ...

2014-10-21

(SALT LAKE CITY)—Workers punching in for the graveyard shift may be better off not eating high-iron foods at night so they don't disrupt the circadian clock in their livers.

Disrupted circadian clocks, researchers believe, are the reason that shift workers experience higher incidences of type 2 diabetes, obesity and cancer. The body's primary circadian clock, which regulates sleep and eating, is in the brain. But other body tissues also have circadian clocks, including the liver, which regulates blood glucose levels.

In a new study in Diabetes online, University ...

2014-10-21

DURHAM, N.H. –- Crewed missions to Mars remain an essential goal for NASA, but scientists are only now beginning to understand and characterize the radiation hazards that could make such ventures risky, concludes a new paper by University of New Hampshire scientists.

In a paper published online in the journal Space Weather, associate professor Nathan Schwadron of the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) and the department of physics says that due to a highly abnormal and extended lack of solar activity, the solar wind is exhibiting extremely ...

2014-10-21

DURHAM, N.H. – Six percent of U.S. children and youth missed a day of school over the course of a year because they were the victim of violence or abuse at school. This was a major finding of a study on school safety by University of New Hampshire researchers published this month in the Journal of School Violence.

"This study really highlights the way school violence can interfere with learning," says lead author David Finkelhor, professor of sociology and director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center (CCRC) at UNH. "Too many kids are missing school ...

2014-10-21

New research shows that a preservation technique known as sequential subnormothermic ex vivo liver perfusion (SNEVLP) prevents ischemic type biliary stricture following liver transplantation using grafts from donations after cardiac death (DCD). Findings published in Liver Transplantation, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, indicate that the preservation of DCD grafts using SNEVLP versus cold storage reduces bile duct and endothelial cell injury post transplantation.

The shortage ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Special UO microscope captures defects in nanotubes

University of Oregon chemists provide a detailed view of traps that disrupt energy flow, possibly pointing toward improved charge-carrying devices