(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. — Wisconsin is famous for its ice fishers — the stalwarts who drill holes through lake ice in the hope of catching a winter dinner. Less well known are the state's big-league ice drillers — specialists who design huge drills and use them to drill deep into ice in Greenland and Antarctica, places where even summer seems like winter.

The quarry at these drills includes some of the biggest catches in science.

A hot-water drill designed and built at the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Space Science and Engineering Center (SSEC) and the Physical Sciences Laboratory was critical to the success of IceCube, a swarm of neutrino detectors at the South Pole that has opened a new frontier in astronomy.

Hollow coring drills designed and managed by UW-Madison's Ice Drilling Design and Operations (IDDO) program are used to extract ice cores that can analyze the past atmosphere, says Shaun Marcott, an assistant professor of geoscience at UW-Madison. Marcott was the first author of a paper published today in the journal Nature documenting carbon dioxide in the atmosphere between 23,000 and 9,000 years ago, based on data from an 11,000-foot hole in Antarctica.

The ice drilling program traces its roots to Charles Bentley, a legendary UW-Madison glaciologist and polar expert. The program is funded by the National Science Foundation and housed in the Space Science and Engineering Center.

"Building on Charlie's achievements, IceCube enhanced our competency of drilling expertise," says IDDO principal investigator Mark Mulligan. "A 2000 award from the National Science Foundation brought in more engineers and technicians who understand coring and drilling."

IDDO program director Kristina Slawny spent six austral summers on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Divide project, which provided cores for Marcott's climate study. "It's an experience like no other," she says. "We sleep in unheated single tents that get really warm in the day and quite cold at night."

Crew compatibility is "huge," says Slawny, "and in a remote environment we focus on it, so we've had really good continuity in our driller hiring. Once a group has worked together, we want them to stay. When everyone is cold and tired, they can get agitated easily, but for the most part, the crew was happy to be down there."

Still, "everything goes wrong, even the stuff you don't expect," she says. "One year it's mechanical, the next year it's electrical. One of our staffers, Jay Johnson, is a brilliant engineer and machinist who can fix anything, but it can take long hours and sleepless nights to keep the drill running."

Many projects under development require mobile drills, says Mulligan. "The science community has said we need a certain type of core in a certain location, but you may only be able to get there with a helicopter or small plane. That forces us to design smaller, or make something that can be set up relatively quickly. Agile and mobile are very big words."

As concerns about the climatic effects of greenhouse gases mount, Marcott says deep, old ice offers a ground-truthing function. "How do you know that today's carbon dioxide variations are even meaningful?" he asks. "We have only 50 years of instrument data."

Climate studies require a much longer horizon, Marcott adds. "When I measure CO2 from 20,000 years ago, I actually have air from 20,000 years ago, and so I can measure the concentration of CO2 directly. There is no other way to do that."

Much of the credit, Marcott says, is due to UW's ace ice drillers. "Without the ice cores being as pristine as they are, without the drillers being able to take out every single core unbroken to provide us with a 70,000-year record of CO2, we would not be able to understand how this powerful greenhouse gas has affected our planet in the past."

Today, carbon dioxide is growing at 2 parts per million per year — 20 times faster than the preindustrial situation recorded in the ice cores. But even at the slower rate, climate reacted very quickly to changing levels of the key greenhouse gas, Marcott says. "It's not just a gradual change from an ice age to an interglacial. We need to know how the Earth system works, but without these ice cores, and the great effort from the drilling team, we would not be in a position to know."

INFORMATION:

—David Tenenbaum, 608-265-8549, djtenenb@wisc.edu

CONTACT: Kristina Slawny, kristina.slawny@ssec.wisc.edu, 608-263-6178 (prefers email for first contact)

Philadelphia, PA, October 30, 2014 – A common complication, gestational diabetes affects approximately 6-7% of pregnant women. Currently, screening is done in two steps to help identify patients most at risk; however, the suggested levels for additional testing were based on singleton pregnancy data. Now investigators have analyzed data from twin pregnancies and have determined that the optimal first step cutoff for additional screening appears to be a blood sugar level equal to or greater than 135 mg/dL for women carrying twins. Their findings are published in the ...

MAYWOOD, Ill. (Date) – During the first 24 hours after a stroke, attention to detail --such as hospital bed positioning -- is critical to patient outcomes.

Most strokes are caused by blood clots that block blood flow to the brain. Sitting upright can harm the patient because it decreases blood flow and oxygen to the brain just when the brain needs more blood.

Thus, it's reasonable to keep patients lying flat or as nearly flat as possible, according to a report in the journal MedLink Neurology by Loyola University Medical Center neurologist Murray Flaster, MD, ...

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Architecture imitates life, at least when it comes to those spiral ramps in multistory parking garages. Stacked and connecting parallel levels, the ramps are replications of helical structures found in a ubiquitous membrane structure in the cells of the body.

Dubbed Terasaki ramps after their discoverer, they reside in an organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a network of membranes found throughout the cell and connected to and surrounding the cell nucleus. Now, a trio of scientists, including UC Santa Barbara biological physicist ...

The heart holds its own pool of immune cells capable of helping it heal after injury, according to new research in mice at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Most of the time when the heart is injured, these beneficial immune cells are supplanted by immune cells from the bone marrow, which are spurred to converge in the heart and cause inflammation that leads to further damage. In both cases, these immune cells are called macrophages, whether they reside in the heart or arrive from the bone marrow. Although they share a name, where they originate appears ...

BOSTON — Findings published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation show that imperceptible vibratory stimulation applied to the soles of the feet improved balance by reducing postural sway and gait variability in elderly study participants. The vibratory stimulation is delivered by a urethane foam insole with embedded piezoelectric actuators, which generates the mechanical stimulation. The study was conducted by researchers from the Institute for Aging Research (IFAR) at Hebrew SeniorLife, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the Wyss Institute for ...

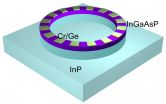

A significant breakthrough in laser technology has been reported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley. Scientists led by Xiang Zhang, a physicist with joint appointments at Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley, have developed a unique microring laser cavity that can produce single-mode lasing even from a conventional multi-mode laser cavity. This ability to provide single-mode lasing on demand holds ramifications for a wide range of applications including optical metrology and ...

Lab-grown tissues could one day provide new treatments for injuries and damage to the joints, including articular cartilage, tendons and ligaments.

Cartilage, for example, is a hard material that caps the ends of bones and allows joints to work smoothly. UC Davis biomedical engineers, exploring ways to toughen up engineered cartilage and keep natural tissues strong outside the body, report new developments this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"The problem with engineered tissue is that the mechanical properties are far from those ...

Washington, DC—The Endocrine Society today issued a Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly, a rare condition caused by excess growth hormone in the blood.

The CPG, entitled "Acromegaly: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline," appeared in the November 2014 issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism (JCEM), a publication of the Endocrine Society.

Acromegaly is usually caused by a non-cancerous tumor in the pituitary gland. The tumor manufactures too much growth hormone and spurs the body to overproduce ...

Chicago, October 30, 2014—Analysis of data from an institutional patient registry on stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) indicates excellent long-term, local control, 79 percent of tumors, for medically inoperable, early stage lung cancer patients treated with SBRT from 2003 to 2012, according to research presented today at the 2014 Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology. The Symposium is sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), the International Association for the Study ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. – You have to be at least 2 years old to be covered by U.S. dietary guidelines. For younger babies, no official U.S. guidance exists other than the general recommendation by national and international organizations that mothers exclusively breastfeed for at least the first six months.

So what do American babies eat?

That's the question that motivated researchers at the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences to study the eating patterns of American infants at 6 months and 12 months old, critical ages for the development of ...