(Press-News.org) What sounds counter-intuitive to an activity commonly perceived as quiet is the broad recommendation of scientists at Michigan State University (MSU) recommending that small-scale fishing in the world's freshwater bodies must have a higher profile to best protect global food security.

In this month's journal Global Food Security, scientists note that competition for freshwater is ratcheting up all over the world for municipal use, hydropower, industry, commercial development, and irrigation. Rivers are being dammed and rerouted, lakes and wetlands are being drained, fish habitats are being altered, nutrients are being lost, and inland waters throughout the world are changing in ways, big and small, that affect fish.

Yet while the commercial fishing enterprises in oceans are accounted for, millions of individuals who fish for subsistence, livelihoods, or recreation are largely unaccounted for. It's a collective voice researchers say need to be heard.

"All over the world there are people catching fish to feed themselves and their families," said So-Jung Youn, a master's degree student in MSU's Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability (CSIS). "Individually it may not seem like much, but it adds up to a significant amount of food, and it's a perspective people too often forget."

Youn is the first author of "The importance of inland capture fisheries to global food security." The paper observes that globally, just 156 of more than 230 countries and territories reported their inland capture fisheries production to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in 2010, and that even those reporting have inaccurate and grossly underestimated data. When accurately assessed, the amount of freshwater fish caught could equal the current amount of marine fish caught.

As a result, even though the people pulling in the carp, tilapia and other freshwater fish are playing an important role in enhancing local food security, their importance is not being accurately reflected in the production values that are reported and thus are often invisible in policies and decisions regarding food security and water use.

"It's not a question of whether we should stop using water for other purposes, but we need to consider what harms are being created, and if that can be mitigated, " Youn said. "People are losing jobs and important sources of food because fish habitats are being degraded, greatly reducing fish production in these waters."

William Taylor, MSU University Distinguished Professor in Global Fisheries Systems, says what water is used for is a growing global battle and that fish are a significant part of global food security. That means, he says, fish need a voice – and part of that voice are the people who eat them.

"Right now, society looks at water and rarely sees or values the fish within," Taylor said. "As such, society often unwittingly uses the water and the land in ways that negatively impact fish habitat, ultimately affecting fish production and distribution."

Fishing on the Amazon at sunsetIn January, Taylor is to chair the Global Conference on Inland at FAO Headquarters in Rome. The conference will address the challenges and opportunities for freshwater fisheries on a global scale, attempting to make the invisible visible to society.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Youn and Taylor, the paper is written by Abigail Lynch, a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) research scientist and CSIS alumna and Doug Beard Jr., chief of the USGS National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center; Ian Cowx is professor of applied fisheries science and director of Hull International Fisheries Institute in United Kingdom; Devin Bartley is FAO senior fisheries resource officer and Felicia Wu is the John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at MSU.

The research was funded by the USGS National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center.

Noonan syndrome is a rare disease that is characterised by a set of pathologies, including heart, facial and skeletal alterations, pulmonary stenosis, short stature, and a greater incidence of haematological problems (mainly juvenile myeloid leukaemia, or childhood leukaemia). There is an estimated incidence of 1 case for every 1,000–2,500 births, and calculations show some 20,000–40,000 people suffer from the disease in Spain. From a genetic point of view, this syndrome is associated to mutations in 11 different genes —the K-Ras gene among them— ...

PATIENTS with a specific type of oesophageal cancer survived longer when they were given the latest lung cancer drug, according to trial results being presented at the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Cancer Conference today (Wednesday).

Up to one in six patients with oesophageal cancer were found to have EGFR duplication in their tumour cells and taking the drug gefitinib, which targets this fault, boosted their survival by up to six months, and sometimes beyond.

This is the first treatment for advanced oesophageal cancer shown to improve survival in patients ...

Fatih Uckun, Jianjun Cheng and their colleagues have taken the first steps towards developing a so-called "smart bomb" to attack the most common and deadly form of childhood cancer — called B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

In a November study in the new peer-reviewed, open-access journal EBioMedicine, they describe how this approach could eventually prove lifesaving for children who have relapsed after initial chemotherapy and face a less than 20 percent chance of long-term survival.

"We knew that we could kill chemotherapy-resistant leukemia cells ...

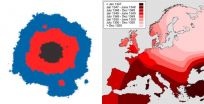

The current Ebola outbreak shows how quickly diseases can spread with global jet travel.

Yet, knowing how to predict the spread of these epidemics is still uncertain, because the complicated models used are not fully understood, says a University of California, Berkeley biophysicist.

Using a very simple model of disease spread, Oskar Hallatschek, assistant professor of physics, proved that one common assumption is actually wrong. Most models have taken for granted that if disease vectors, such as humans, have any chance of "jumping" outside the initial outbreak area ...

Researchers using a new type of tracking device on female elephant seals have discovered that adding body fat helps the seals dive more efficiently by changing their buoyancy.

The study, published November 5 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, looked at the swimming efficiency of elephant seals during their feeding dives and how that changed in the course of months-long migrations at sea as the seals put on more fat. The results showed that when elephant seals are neutrally buoyant--meaning they don't float up or sink down in the water--they spend less energy ...

A University of Oregon researcher wants those "R" words to resonate among young athletes. They are key terms used in an online educational tool designed to teach coaches, educators, teens and parents about concussions.

Brain 101: The Concussion Playbook successfully increased knowledge and attitudes related to brain injuries among students and parents in a study that compared its use in 12 high schools with the usual care practices of 13 other high schools during the fall 2011 sports season. The findings are online ahead of print in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Participants, ...

A study led by a researcher from Plymouth University in the UK, has discovered that the inhibition of a particular mitochondrial fission protein could hold the key to potential treatment for Parkinson's Disease (PD).

The findings of the research are published today, 5th November 2014, in Nature Communications.

PD is a progressive neurological condition that affects movement. At present there is no cure and little understanding of why some people get the condition. In the UK one on 500 people, around 127,000, have PD.

The debilitating movement symptoms of the disease ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Millions of people with diabetes take medicine to ease the shooting, burning nerve pain that their disease can cause. And new research suggests that no matter which medicine their doctor prescribes, they'll get relief.

But some of those medicines cost nearly 10 times as much as others, apparently with no major differences in how well they ease pain, say a pair of University of Michigan Medical School experts in a new commentary in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

That makes cost -- not effect -- a crucial factor in deciding which medicine ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — A new study by a Florida State University researcher reveals that a new dietary supplement is superior to calcium and vitamin D when it comes to bone health.

Over 12 months, Bahram H. Arjmandi, Margaret A. Sitton Professor in the Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sciences and Director of the Center for Advancing Exercise and Nutrition Research on Aging (CAENRA) at Florida State, studied the impact of the dietary supplement KoACT® versus calcium and vitamin D on bone loss. KoACT is a calcium-collagen chelate, a compound containing ...

A child's ability to distinguish musical rhythm is related to his or her capacity for understanding grammar, according to a recent study from a researcher at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center.

Reyna Gordon, Ph.D., a research fellow in the Department of Otolaryngology and at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, is the lead author of the study that was published online recently in the journal Developmental Science. She notes that the study is the first of its kind to show an association between musical rhythm and grammar.

Though Gordon emphasizes that more research will be necessary ...