(Press-News.org) Human-caused climate change, ocean acidification and species extinctions may eventually threaten the collapse of civilization, according to some scientists, while other people argue that for political or economic reasons we should allow industrial development to continue without restrictions.

In a new paper, two astrophysicists argue that these questions may soon be resolvable scientifically, thanks to new data about the Earth and about other planets in our galaxy, and by combining the earth-based science of sustainability with the space-oriented field of astrobiology.

"We have no idea how long a technological civilization like our own can last," says University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank. "Is it 200 years, 500 years or 50,000 years? Answering this question is at the root of all our concerns about the sustainability of human society."

"Are we the first and only technologically-intensive civilization in the entire history of the universe?" asks Frank. "If not, shouldn't we stand to learn something from the past successes and failures of these other species?"

In their paper, which appears in the journal Anthropocene, Frank and co-author Woodruff Sullivan call for creation of a new research program to answer questions about humanity's future in the broadest astronomical context. The authors explain: "The point is to see that our current situation may, in some sense, be natural or at least a natural and generic consequence of certain evolutionary pathways."

To frame these questions, Frank and Sullivan begin with the famous Drake equation, a straightforward formula used to estimate the number of intelligent societies in the universe. In their treatment of the equation, the authors concentrate on the average lifetime of a Species with Energy-Intensive Technology (SWEIT). Frank and Sullivan calculate that even if the chances of forming such a "high tech" species are 1 in a 1,000 trillion, there will still have been 1,000 occurrences of a history like own on planets across the "local" region of the Cosmos.

"That's enough to start thinking about statistics," says Frank, "like what is the average lifetime of a species that starts harvesting energy efficiently and uses it to develop high technology."

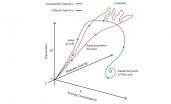

Employing dynamical systems theory, the authors map out a strategy for modeling the trajectories of various SWEITs through their evolution. The authors show how the developmental paths should be strongly tied to interactions between the species and its host planet. As the species' population grows and its energy harvesting intensifies, for example, the composition of the planet and its atmosphere may become altered for long timescales.

Frank and Sullivan show how habitability studies of exoplanets hold important lessons for sustaining the civilization we have developed on Earth. This "astrobiological perspective" casts sustainability as a place-specific subset of habitability, or a planet's ability to support life. While sustainability is concerned with a particular form of life on a particular planet, astrobiology asks the bigger question: what about any form of life, on any planet, at any time?

We don't yet know how these other life forms compare to the ones we are familiar with here on Earth. But for the purposes of modeling average lifetimes, Frank explains, it doesn't matter.

"If they use energy to produce work, they're generating entropy. There's no way around that, whether their human-looking Star Trek creatures with antenna on their foreheads, or they're nothing more than single-cell organisms with collective mega-intelligence. And that entropy will almost certainly have strong feedback effects on their planet's habitability, as we are already beginning to see here on Earth."

"Maybe everybody runs into this bottleneck," says Frank, adding that this could be a universal feature of life and planets. "If that's true, the question becomes whether we can learn anything by modeling the range of evolutionary pathways. Some paths will lead to collapse and others will lead to sustainability. Can we, perhaps, gain some insight into which decisions lead to which kind of path?"

As Frank and Sullivan show, studying past extinction events and using theoretical tools to model the future evolutionary trajectory of humankind--and of still unknown but plausible alien civilizations--could inform decisions that would lead to a sustainable future.

INFORMATION:

About the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is one of the nation's leading private universities. Located in Rochester, N.Y., the University gives students exceptional opportunities for interdisciplinary study and close collaboration with faculty through its unique cluster-based curriculum. Its College, School of Arts and Sciences, and Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences are complemented by its Eastman School of Music, Simon School of Business, Warner School of Education, Laboratory for Laser Energetics, School of Medicine and Dentistry, School of Nursing, Eastman Institute for Oral Health, and the Memorial Art Gallery.

This news release is available in German.

"The technique makes it possible for the first time to remove large organic molecules from associated structures and place them elsewhere in a controlled manner," explains Dr. Ruslan Temirov from Jülich's Peter Grünberg Institute. This brings the scientists one step closer to finding a technology that will enable single molecules to be freely assembled to form complex structures. Research groups around the world are working on a modular system like this for nanotechnology, which is considered imperative for the ...

New research reports that the rate of hospitalization due to hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection has significantly declined in the U.S. from 2002 to 2011. Findings published in Hepatology, a journal of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, show that older patients and those with chronic liver disease are most likely to be hospitalized for HAV. Vaccination of adults with chronic liver disease may prevent infection with hepatitis A and the need for hospitalization.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that each year 1.4 million individuals worldwide ...

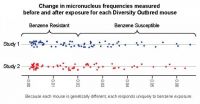

A genetically diverse mouse model is able to predict the range of response to chemical exposures that might be observed in human populations, researchers from the National Institutes of Health have found. Like humans, each Diversity Outbred mouse is genetically unique, and the extent of genetic variability among these mice is similar to the genetic variation seen among humans.

Using these mice, researchers from the National Toxicology Program (NTP), an interagency program headquartered at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), were able to identify ...

WASHINGTON, D.C., November 6, 2014--Short-term certificate programs at community colleges offer limited labor-market returns, on average, in most fields of study, according to new research published today in Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (EEPA), a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association. The results of the study, which focused on community college programs in Washington State, are in line with recent research in other states (Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia) that found only small economic returns from short-term programs. ...

WASHINGTON, DC (November 6, 2014)--In honor of Veterans Day, the peer-reviewed journal Women's Health Issues (WHI) today released a new Special Collection on women veterans' health, with a focus on mental health. The special collection also highlights recent studies addressing healthcare services, reproductive health and cardiovascular health of women veterans.

"In recent years, we have seen the Veterans Administration working to improve care and health outcomes of women veterans and service members," said Chloe Bird, editor-in-chief of Women's Health Issues. "The studies ...

Paramedics respond to a 911 call to find an elderly patient who's having difficulty breathing. Anxious and disoriented, the patient has trouble remembering all the medications he's taking, and with his shortness of breath, speaking is difficult. Is he suffering from acute emphysema or heart failure? The symptoms look the same, but initiating the wrong treatment regimen will increase the patient's risk of severe complications.

Researchers from MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics, working with physicians from Harvard Medical School and the Einstein Medical Center in ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Power outages have never been more costly. Electricity is critical to communication, transportation, commerce and national security systems, and wide-spread or prolonged outages have the potential to threaten public safety and cause millions, even billions, of dollars in damages.

"It doesn't seem that dire until a storm hits, or somebody makes a mistake, and then you are risking a blackout," said Inara Scott, an assistant professor in the College of Business at Oregon State University.

"You have to consider the magnitude of the potential harm ...

High-speed reading of the genetic code should get a boost with the creation of the world's first graphene nanopores - pores measuring approximately 2 nanometers in diameter - that feature a "built-in" optical antenna. Researchers with Berkeley Lab and the University of California (UC) Berkeley have invented a simple, one-step process for producing these nanopores in a graphene membrane using the photothermal properties of gold nanorods.

"With our integrated graphene nanopore with plasmonic optical antenna, we can obtain direct optical DNA sequence detection," says Luke ...

ATLANTA, GA (November 6, 2014) – Whether allergy sufferers have symptoms that are mild or severe, they really only want one thing: relief. So it's particularly distressing that the very medication they hope will ease symptoms can cause different, sometimes more severe, allergic responses.

According to a presentation at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) Annual Scientific Meeting, an allergic response to a medication for allergies can often go undiagnosed. The presentation sheds light on adverse responses to topical skin preparations; ...

Berlin, Germany (November, 2014) – A specimen of the ancient horse Eurohippus messelensis has been discovered in Germany that preserves a fetus as well as parts of the uterus and associated tissues. It demonstrates that reproduction in early horses was very similar to that of modern horses, despite great differences in size and structure. Eurohippus messelensis had four toes on each forefoot and three toes on each the hind foot, and it was about the size of a modern fox terrier. The new find was unveiled at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology ...