(Press-News.org) A study led by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators has identified what appears to be a molecular switch controlling inflammatory processes involved in conditions ranging from muscle atrophy to Alzheimer's disease. In their report published in Science Signaling, the research team found that the action of the signaling molecule nitric oxide on the regulatory protein SIRT1 is required for the induction of inflammation and cell death in cellular and animal models of several aging-related disorders.

"Since different pathological mechanisms have been identified for diseases like type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis and Parkinson's disease, it has been assumed that therapeutic strategies for those conditions should also differ," says Masao Kaneki, MD, PhD, MGH Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, senior author of the paper. "In contrast, our findings identified nitric oxide-mediated inactivation of SIRT1 - believed to be a longevity gene - as a hub of the inflammatory spiral common to many aging-related diseases, clarifying a new preventive molecular target."

Studies have implicated a role for nitric oxide in diabetes, neurodegeneration, atherosclerosis and other aging-related disorders known to involve chronic inflammation. But exactly how nitric oxide exerts those effects - including activation of the inflammatory factor NF-kappaB and the regulatory protein p53, which can induce the death of damaged cells - was not known. SIRT1 is known to suppress the activity of both NF-kappaB and p53, and since its dysregulation has been associated with models of several aging-related conditions, the research team focused on nitric oxide's suppression of SIRT1 through a process called S-nitrosylation.

Cellular experiments revealed that S-nitrosylation inactivates SIRT1 by interfering with the protein's ability to bind zinc, which in turn increases the activation of p53 and of a protein subunit of NF-kappaB. Experiments in mouse models of systemic inflammation, age-related muscle atrophy and Parkinson's disease found that blocking or knocking out NO synthase - the enzyme that induces nitric oxide generation - prevented the cellular and in the Parkinson's model behavioral effects of the diseases. Additional experiments pinpointed the S-nitrosylation of SIRT1 as a critical point in the chain of events leading from nitric oxide expression to cellular damage and death.

"Regardless of the original event that set off this process, once turned on by SIRT1 inactivation, the same cascade of enhanced inflammation and cell death leads to many different disorders," says Kaneki, an associate professor of Anaesthesia at Harvard Medical School. "While we need to confirm that what we found in rodent models operates in human diseases, I believe this process plays an important role in the pathogenesis of conditions including obesity-related diabetes, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease and the body's response to major trauma. We're now trying to identify small molecules that will specifically inhibit S-nitrosylation of SIRT1 and related proteins and suppress this proinflammatory switch."

INFORMATION:

The co-lead authors of the Science Signaling paper are Shohei Shinozaki, PhD, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, and Kyungho Chang, MD, PhD, University of Tokyo School of Medicine, both of whom previously were research fellows at MGH. Additional co-authors include Michihiro Sakai, Nobuyuki Shimizu, Marina Yamada, Tomokazu Tanaka, MD, PhD, Harumasa Nakazawa, MD and Fumito Ichinose, MD, PhD, all of the MGH Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine; and Jonathan S. Stamler, MD, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospital, Cleveland.

Support for the study includes National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK-058127, R01-GM-099921, 5P01-HL-075443-08 and R01-AG-039732; Defense Advanced Research Project Agency grant N66001-13-C-4054; American Diabetes Association grant 7-08-RA-77, and grants from Shriners Hospitals for Children.

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $785 million and major research centers in HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.

November 12, 2014 - "I am the smartest kid in class." We all want our kids to be self-confident, but unrealistic perceptions of their academic abilities can be harmful. These unrealistic views, a new study of eighth-graders finds, damage the a child's relationship with others in the classroom: The more one student feels unrealistically superior to another, the less the two students like each other.

Katrin Rentzsch of the University of Bamberg in Germany first became interested in the effects of such self-perceptions when she was studying how people became labeled as ...

LOS ANGELES -- New research from Keck Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC) bolsters evidence that exposure to tobacco smoke and near-roadway air pollution contribute to the development of obesity.

The study, to be posted online Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2014 in Environmental Health Perspectives, shows increased weight gain during adolescence in children exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke or near-roadway air pollution, compared to children with no exposure to either of these air pollutants. The study is one of the first to look at the combined effects on ...

Applying a thin film of metallic oxide significantly boosts the performance of solar panel cells--as recently demonstrated by Professor Federico Rosei and his team at the Énergie Matériaux Télécommunications Research Centre at Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS). The researchers have developed a new class of materials comprising elements such as bismuth, iron, chromium, and oxygen. These "multiferroic" materials absorb solar radiation and possess unique electrical and magnetic properties. This makes them highly promising for solar technology, ...

VCU Massey Cancer Center and VCU Institute of Molecular Medicine (VIMM) researchers discovered a unique approach to treating pancreatic cancer that may be potentially safe and effective. The treatment method involves immunochemotherapy - a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, which uses the patient's own immune system to help fight against disease. This pre-clinical study, led by Paul B. Fisher, M.Ph., Ph.D., and Luni Emdad, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., found that the delivery of [pIC]PEI - a combination of the already-established immune-modulating molecule, polyinosine-polycytidylic ...

High blood pressure - already a massive hidden killer in Nigeria - is set to sharply rise as the country adopts western lifestyles, a study suggests.

Researchers who conducted the first up-to-date nationwide estimate of the condition in Nigeria warn that this will strain the country's already-stretched health system.

Increased public awareness, lifestyle changes, screening and early detection are vital to tackle the increasing threat of the disease, they say.

High blood pressure - also known as hypertension - is twice as high in Nigeria compared with other East ...

Scientists have demonstrated for the first time that a single-dose, needleless Ebola vaccine given to primates through their noses and lungs protected them against infection for at least 21 weeks. A vaccine that doesn't require an injection could help prevent passing along infections through unintentional pricks. They report the results of their study on macaques in the ACS journal Molecular Pharmaceutics.

Maria A. Croyle and colleagues note that in the current Ebola outbreak, which is expected to involve thousands more infections and deaths before it's over, an effective ...

Geneticists at Heidelberg University Hospital's Department of Molecular Human Genetics have used a new mouse model to demonstrate the way a certain genetic mutation is linked to a type of autism in humans and affects brain development and behavior. In the brain of genetically altered mice, the protein FOXP1 is not synthesized, which is also the case for individuals with a certain form of autism. Consequently, after birth the brain structures degenerate that play a key role in perception. The mice also exhibited abnormal behavior that is typical of autism. The new mouse ...

An electronic "tongue" could one day sample food and drinks as a quality check before they hit store shelves. Or it could someday monitor water for pollutants or test blood for signs of disease. With an eye toward these applications, scientists are reporting the development of a new, inexpensive and highly sensitive version of such a device in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

S. V. Litvinenko and colleagues explain that an electronic tongue is an analytical instrument that mimics how people and other mammals distinguish tastes. Tiny sensors detect substances ...

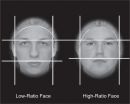

The structure of a soccer player's face can predict his performance on the field--including his likelihood of scoring goals, making assists and committing fouls--according to a study led by a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The scientists studied the facial-width-to-height ratio (FHWR) of about 1,000 players from 32 countries who competed in the 2010 World Cup. The results, published in the journal Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, showed that midfielders, who play both offense and defense, and forwards, who lead the offense, with higher FWHRs ...

Queensland University of Technology (QUT) researchers have found the habit of Googling for an online diagnosis before visiting the doctor can be a powerful predictor of infectious diseases outbreaks.

Now studies by the same Brisbane-based researchers show combining information from monitoring internet search metrics such as Baidu (China's equivalent of Google), with a web-based infectious disease alert system from reported cases and environmental factors hold the key to improving early warning systems and reducing the deadly effects of dengue fever in China.

Dr Wenbiao ...