(Press-News.org) People can gauge the accuracy of their decisions, even if their decision making performance itself is no better than chance, according to a new study published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

In the study, people who showed chance-level decision making still reported greater confidence about decisions that turned out to be accurate and less confidence about decisions that turned out to be inaccurate. The findings suggest that the participants must have had some unconscious insight into their decision making, even though they failed to use the knowledge in making their original decision, a phenomenon the researchers call "blind insight."

"The existence of blind insight tells us that our knowledge of the likely accuracy of our decisions -- our metacognition -- does not always derive directly from the same information used to make those decisions, challenging both everyday intuition and dominant theoretical models of metacognition," says researcher Ryan Scott of the University of Sussex in the UK.

Metacognition, the ability to think about and evaluate our own mental processes, plays a fundamental role in memory, learning, self-regulation, social interaction, and signals marked differences in mental states, such as with certain mental illnesses or states of consciousness.

"Consciousness research reveals many instances in which people are able to make accurate decisions without knowing it, that is, in the absence of metacognition" says Scott. The most famous example of this is blindsight, in which people are able to discriminate visual stimuli even though they report that they can't see the stimuli and that their discrimination judgments are mere guesses.

Scott and colleagues wanted to know whether the opposite scenario -- metacognitive insight in the absence of accurate decision making -- could also occur:

"We wondered: Can a person lack accuracy in their decisions but still be more confident when their decision is right than when it's wrong?" Scott explains.

The researchers looked at data from 450 student volunteers, aged 18 to 40. The volunteers were presented with a "short-term memory task" in which they were shown strings of letters and were asked to memorize them. After the memory task, the researchers revealed that the order of the letters in the strings actually obeyed a complex set of rules.

The participants were then shown a new set of letter strings, half of which followed the same rules, and were asked to classify which of the strings were "correct." For each string, they rated whether or not it followed the rules and how confident they were in that judgment.

To explore the relationship between decision making and metacognition, the researchers examined data from participants whose performance was at or below chance for the first 75% of the test strings (inaccurate decision makers) and data from participants who performed significantly above chance over the same proportion of trials (accurate decision makers).

Looking at the data from the remaining 25% of trials, the researchers found that, despite their overall chance-level performance, inaccurate decision makers made reliable confidence judgments about their decisions. In fact, the reliability of their confidence judgments did not differ from the reliability of confidence judgments made by accurate decision makers.

In other words, the participants exhibited the opposite dissociation to blindsight: They knew when they were wrong, despite being unable to make accurate judgments. The researchers decided to name the phenomenon "blind insight" to reflect that relationship.

Taken together, these findings do not support the type of bottom-up, hierarchical model of metacognition proposed by many researchers. Using signal detection theory, such models hold that low-level sensory signals drive first-order judgments (e.g., "Is this correct?") and, ultimately, second-order metacognitive judgments (e.g., "How confident am I about whether this is correct?").

In this study, however, there was no reliable signal driving decision making for inaccurate decision makers; thus, according to the established models, there would be no signal available to drive second-order confidence judgments. The fact that confidence was found to be greater for correct responses demonstrates that such a hierarchical model is flawed. Based on these findings, the researchers argue that there must be other pathways that lead to metacognitive insight, and a radical revision of models of metacognition is required.

INFORMATION:

The full article is available online at: http://pss.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/11/11/0956797614553944.full

Study co-authors include Zoltan Dienes, Adam B. Barrett, Daniel Bor, and Anil K. Seth of the University of Sussex.

All data and materials have been made publicly available via Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/ivdk4/files/. The complete Open Practices Disclosure for this article can be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data. This article has received badges for Open Data and Open Materials. More information about the Open Practices badges can be found at https://osf.io/tvyxz/wiki/view/ and http://pss.sagepub.com/content/25/1/3.full.

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant No. RES-062-23-1975), an Engineering and Physical Sciences Leadership Fellowship to A. K. Seth (Grant No. EP/G007543/1), an Engineering and Physical Sciences Fellowship to A. B. Barrett (Grant No. EP/L005131/1), the European Research Council project Collective Experience of Empathic Data Systems project (Grant No. 258749; FP7-ICT-2009-5), and a donation from the Dr. Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation via the Sackler Centre for Consciousness Science.

For more information about this study, please contact: Ryan B. Scott at r.b.scott@sussex.ac.uk.

The APS journal Psychological Science is the highest ranked empirical journal in psychology. For a copy of the article "Blind Insight: Metacognitive Discrimination Despite Chance Task Performance" and access to other Psychological Science research findings, please contact Anna Mikulak at 202-293-9300 or amikulak@psychologicalscience.org.

Philadelphia, PA (November 13, 2014) -- Patients on dialysis are very vulnerable during emergencies or disasters, but many are unprepared for such situations, according to two studies that will be presented at ASN Kidney Week 2014 November 11¬-16 at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia, PA.

Dialysis patients are highly dependent on technologies to sustain their lives, with ongoing needs for transportation, electricity, and water for the dialysis apparatus. Interruption of these needs by a natural disaster can be devastating.

Naoka Murakami, MD, PhD ...

TORONTO, Nov. 13, 2014--Canadians with cystic fibrosis are living almost 20 years longer than they did two decades ago, according to a research paper published today.

The median survival age was 49.7 years in 2012, up from 31.9 years in 1990, Dr. Anne Stephenson, a respirologist and research at St. Michael's Hospital wrote in the European Respiratory Journal. Since the paper was written, Dr. Stephenson has updated the median survival age to include Cystic Fibrosis Canada data from 2013 and reported the median age of survival has in fact reached 50.9 years.

In addition, ...

Scientists from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles describe a new distinctive fly species of the highly diverse genus Megaselia. The study published in the Biodiversity Data Journal proposes an innovative method for streamlining Megaselia species descriptions to save hours of literature reviews and comparisons.

The new species, M. shadeae, is easily distinguished by a large, central, pigmented and bubble-like wing spot. The description is part of the the Zurquí All Diptera Biodiversity Inventory (ZADBI) project, and represents the first of an incredible ...

Mice bred to carry a gene variant found in a third of ALS patients have a faster disease progression and die sooner than mice with the standard genetic model of the disease, according to Penn State College of Medicine researchers. Understanding the molecular pathway of this accelerated model could lead to more successful drug trials for all ALS patients.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a degeneration of lower and upper motor neurons in the brainstem, spinal cord and the motor cortex. The disease, which affects 12,000 Americans, ...

Philadelphia, November 13, 2014 - Associations between opioid-related overdoses and increased prescription of opioids for chronic noncancer pain are well known. But some suggest that overdose occurs predominately in individuals who obtain opioids from nonmedical sources. In a new study published in the November issue of the journal PAIN®, researchers in Denmark found an increased risk of death associated with chronic pain without opioid treatment, as well as an even higher risk among those prescribed opioids for long-term use and a somewhat lower risk associated with ...

Scientists at the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore (CSI Singapore) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and their collaborators have developed a scoring scheme that predicts the ability of cancer cells to spread to other parts of the body, a process known as metastasis. This system, which is the first of its kind, opens up the possibility to explore new treatments that suppress metastasis in cancer patients. The findings were published in EMBO Molecular Medicine in September.

Led by Professor Jean Paul Thiery, Senior Principal Investigator, and Dr Ruby Huang, ...

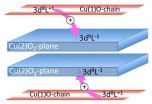

Swedish materials researchers at Linköping and Uppsala University and Chalmers University of Technology, in collaboration with researchers at the Swiss Synchrotron Light Source (SLS) in Switzerland investigated the superconductor YBa2Cu3O7-x (abbreviated YBCO) using advanced X-ray spectroscopy.

Their findings are published in the Nature journal Science Reports.

YBCO is a well-known ceramic copper-based material that can conduct electricity without loss (superconductivity) when it is cooled below its critical temperature Tc=-183° C. Since the resistance and ...

People on the autistic spectrum may struggle to recognise social cues, unfamiliar people or even someone's gender because of an inability to interpret changing facial expressions, new research has found.

According to the study by academics at Brunel University London, adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), though able to recognise static faces, struggle with tasks that require them to discriminate between sequences of facial motion or to use facial motion as a cue to identity.

The research supports previous evidence to suggest that impairments in perceiving biological ...

Membranes are thin walls that surround cells and protect their interior from the environment. These walls are composed of phospholipids, which, due to their amphiphilic nature, form bilayers with dis-tinct chemical properties: While the outward-facing headgroups are charged, the core of the bilayer is hydrophobic, which prevents charged molecules from passing through. The controlled flow of ions across the membrane, which is essential for the transmission of nerve impulses, is facilitated by ion channels, membrane proteins that provide gated pathways for ions. Analogous ...

A cat always lands on its feet. At least, that's how the adage goes. Karen Liu hopes that in the future, this will be true of robots as well.

To understand the way feline or human behavior during falls might be applied to robot landings, Liu, an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing (IC) at Georgia Tech, delved into the physics of everything from falling cats to the mid-air orientation of divers and astronauts.

In research presented at the 2014 IEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Liu shared her studies of mid-air ...