Infection-fighting B cells go with the flow

2014-11-17

(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

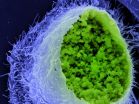

The movement of bone marrow B cells was limited in the absence of VCAM-1, as shown in this time-lapse video. B cells (green) were tracked before (left) and after (right)...

Click here for more information.

Newly formed B cells take the easy way out when it comes to exiting the bone marrow, according to a study published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

For infection-fighting T and B cells to defend the body, they must first leave their birthplace--the thymus for T cells and bone marrow for B cells. T cell migration within and eventual exit from the thymus are active processes governed by expression of specific cell surface receptors (called GPCRs) that respond to external attractants and cause the cell to crawl toward exit sites. B cells are retained in the bone marrow by a similar mechanism controlled by a GPCR called CXCR4, which binds to a bone marrow-resident protein and also increases the expression of sticky "integrin" molecules, effectively tethering the cells in place.

But when it comes to leaving the bone marrow, B cells can afford to be lazy. João Pereira and colleagues at Yale University School of Medicine show that B cells actively migrate around the bone marrow with the help of CXCR4 and an integrin called VCAM-1. Without CXCR4, the cells slowed down and many stopped moving entirely, in part due to decreased expression of VCAM-1. For those cells near exit sites, decreased CXCR4 and VCAM-1 allowed them to be passively swept out of the bone marrow with the blood flow.

Why immune cells use different exit strategies in different organs is not completely clear. But the authors suggest that the go-with-the-flow strategy of the bone marrow may be due to its role in the production of red blood cells, which do not express molecules required for active crawling.

INFORMATION:

Beck, T.C., et al. 2014. J. Exp. Med. doi:10.1084/jem.20140457

About The Journal of Experimental Medicine

The Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM) is published by The Rockefeller University Press. All editorial decisions on manuscripts submitted are made by active scientists in conjunction with our in-house scientific editors. JEM content is posted to PubMed Central, where it is available to the public for free six months after publication. Authors retain copyright of their published works and third parties may reuse the content for non-commercial purposes under a creative commons license. For more information, please visit http://www.jem.org

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-17

This news release is available in German.

Infections due to the sexually transmitted bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis often remain unnoticed. The pathogen is not only a common cause of female infertility; it is also suspected of increasing the risk of abdominal cancer. A research team at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin has now observed the breakdown of an important endogenous protective factor in the course of chlamydial infection. By activating the destruction of p53 protein, the bacterium blocks a key protective mechanism of infected cells, ...

2014-11-17

Doctors tell us that the frenzied pace of the modern 24-hour lifestyle -- in which we struggle to juggle work commitments with the demands of family and daily life -- is damaging to our health. But while life in the slow lane may be better, will it be any longer? It will if you're a reptile.

A new study by Tel Aviv University researchers finds that reduced reproductive rates and a plant-rich diet increases the lifespan of reptiles. The research, published in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography, was led by Prof. Shai Meiri, Dr. Inon Scharf, and doctoral student ...

2014-11-17

If you want to see into the future, you have to understand the past. An international consortium of researchers under the auspices of the University of Bonn has drilled deposits on the bed of Lake Van (Eastern Turkey) which provide unique insights into the last 600,000 years. The samples reveal that the climate has done its fair share of mischief-making in the past. Furthermore, there have been numerous earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The results of the drilling project also provide a basis for assessing the risk of how dangerous natural hazards are for today's population. ...

2014-11-17

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Two or more serious hits to the head within days of each other can interfere with the brain's ability to use sugar - its primary energy source - to repair cells damaged by the injuries, new research suggests.

The brain's ability to use energy is critical after an injury. In animal studies, Ohio State University scientists have shown that brain cells ramp up their energy use six days after a concussion to recover from the damage. If a second injury occurs before that surge of energy use starts, the brain loses its best chance to recover.

In mice, ...

2014-11-17

Mikhail Kosiborod, M.D., of Saint Luke's Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of the drug zirconium cyclosilicate in patients with hyperkalemia (higher than normal potassium levels). The study appears in JAMA and is being released to coincide with its presentation at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2014.

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte disorder which can cause potentially life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias and is associated with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and diabetes mellitus. ...

2014-11-17

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University-Dartmouth College team has identified genes and regulatory patterns that allow some organisms to alter their body form in response to environmental change.

Understanding how an organism adopts a new function to thrive in a changing environment has implications for molecular evolution and many areas of science including climate change and medicine, especially in regeneration and wound healing.

The study, which appears in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, provides insight into phenotypic plasticity, a phenomenon that ...

2014-11-17

November 17, 2014, PORTLAND, Ore. -- People who received automated reminders were more likely to refill their blood pressure and cholesterol medications, according to a study published today in a special issue of the American Journal of Managed Care.

The study, which included more than 21,000 Kaiser Permanente members, found that the average improvement in medication adherence was only about 2 percentage points, but the authors say that in a large population, even small changes can make a big difference.

"This small jump might not mean a lot to an individual patient, ...

2014-11-17

This news release is available in Spanish.

Although maize was originally domesticated in Mexico, the country's average yield per hectare is 38% below the world's average. In fact, Mexico imports 30% of its maize from foreign sources to keep up with internal demand.

To combat insect pests, Mexican farmers rely primarily on chemical insecticides. Approximately 3,000 tons of active ingredient are used each year just to manage the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda), in addition to even more chemicals used to control other pests such as the corn earworm (Helicoverpa ...

2014-11-17

In the aquatic environment, suction feeding is far more common than biting as a way to capture prey. A new study shows that the evolution of biting behavior in eels led to a remarkable diversification of skull shapes, indicating that the skull shapes of most fish are limited by the structural requirements for suction feeding.

"When you look at the skulls of biters, the diversity is astounding compared to suction feeders," said Rita Mehta, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz.

With more than 800 species, including both suction feeders ...

2014-11-17

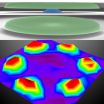

For the first time, scientists have vividly mapped the shapes and textures of high-order modes of Brownian motions--in this case, the collective macroscopic movement of molecules in microdisk resonators--researchers at Case Western Reserve University report.

To do this, they used a record-setting scanning optical interferometry technique, described in a study published today in the journal Nature Communications.

The new technology holds promise for multimodal sensing and signal processing, and to develop optical coding for computing and other information-processing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Infection-fighting B cells go with the flow