(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA - November 17, 2014 - For decades, scientists thought drug addiction was the result of two separate systems in the brain--the reward system, which was activated when a person used a drug, and the stress system, which kicked in during withdrawal.

Now scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that these two systems are actually linked. Their findings, published November 17 in the journal Nature Neuroscience, show that in the core of the brain's reward system are specific neurons that are active both with use of and withdrawal from nicotine. The researchers believe the same neurons may be active in responses to many addictive drugs.

"If we can find a way to target those neurons in humans, maybe we can reduce the 'high' produced by the drug and reduce the withdrawal symptoms," said Olivier George, assistant professor at TSRI and senior author of the new study.

Mysterious Neurons

Until now, the area of the brain where these neurons are found, called the ventral tegmental area (VTA), had only been associated with the reward system--not stress from withdrawal. The neurons in the VTA were known to produce dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to feelings of pleasure.

Five years ago, George was sure there had been a mistake when Taryn Grieder, a staff scientist in Derek van der Kooy's lab at the University of Toronto, who was collaborating with George on this project, detected a stress peptide in the VTA. This peptide, called corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), is associated with anxiety and depression. Grieder, now first author of the new study, ran the test again and got the same weird result. She then ran a third test: same result.

George decided to take a closer look at the VTA and worked closely with Paul Sawchenko, professor at the Salk Institute who was part of the group that originally discovered CRF, to use radioactive RNA markers to detect CRF in brain samples from rodents.

At first, Sawchenko did not find anything unusual. Then one day, Sawchenko and George found themselves staring at an X-ray film of a mouse's VTA when they suddenly spotted tiny black dots on the X-ray film--the CRF-producing neurons where they had never been seen before.

They reminded George of pictures sent back from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope showing dots of light from unknown stars.

"If you look in a textbook, these neurons don't exist in the VTA," said George. "That was the most exciting day of my career."

A New Framework

Following up on these unexpected findings, the researchers looked at the role of these neurons in nicotine addiction.

They studied brain samples from mice and rats that were raised with chronic exposure to nicotine and had developed nicotine dependence--similar to a heavy smoker going through two packs a day. They found that CRF-producing neurons in the VTA were activated during withdrawal, and they examined brain samples from humans, showing that the same CRF-producing VTA neurons are present.

The researchers also tested whether CRF production in the VTA was linked to escalation of nicotine intake in rodents that had withdrawn from the drug and then had nicotine access restored. Previous studies had shown that in rodents--and in humans--those who relapsed began consuming more nicotine than they did when first exposed to the drug. To test whether this behavior was linked to neurons in the VTA, the researchers targeted a gene in the neurons to decrease the production of CRF during withdrawal. They found that rodents with less CRF in the VTA did not escalate their nicotine intake during a second round of access to the drug.

Now that researchers have found a link between the reward and stress systems, George thinks of the systems working together as one "motivational" system. The "high" of dopamine motivates a person to keep smoking, and the stress of withdrawal motivates a person not to quit.

"That changes the whole conceptual framework," said George. "We have to look at everything again, going back to the 1970s. It's possible that when you activate those neurons, you have the reward system that's activated--you have this euphoria, this high--but at the same time you activate this stress peptide."

George hopes the recent study will help researchers develop drugs or genetic therapies to target these neurons. "It's a new road to finding treatments for people," he said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to George, Grieder and Sawchenko, other authors of the study, "VTA CRF neurons mediate the aversive effects of nicotine withdrawal and promote intake escalation," include Hector Vargas-Perez, Michal Chwalek, Geith Maal-Bared, Laura Clarke and Derek van der Kooy of the University of Toronto; Laura A. Tan of the Salk Institute; Pascale Koebel of the Université of Strasbourg; Brigette L. Kieffer of the Université of Strasbourg and McGill University; Andrew Tapper of the University of Massachusetts Medical Science; George F. Koob of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; and Melissa Herman, Ami Cohen, John Frieling, Joel E. Schlosburg, Elena Crawford, Vez Canonigo, Pietro Sanna and Marisa Roberto of TSRI.

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA023597 and DA035371), U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA021491, AA015566, F32 AA020430, AA006420, AA016658 and INIA AA013498), Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (12RT-0099), U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK026741) and the Clayton Medical Research Foundation.

Joseph B. Muhlestein, M.D., of the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute, Murray, Utah, and colleagues examined whether screening patients with diabetes deemed to be at high cardiac risk with coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) would result in a significant longterm reduction in death, heart attack, or hospitalization for unstable angina. The study appears in JAMA and is being released to coincide with its presentation at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2014.

Diabetes mellitus is the most important coronary artery disease ...

Yasuo Ikeda, M.D., of Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan, and colleagues examined whether once-daily, low-dose aspirin would reduce the total number of cardiovascular (CV) events (death from CV causes, nonfatal heart attack or stroke) compared with no aspirin in Japanese patients 60 years or older with hypertension, diabetes, or poor cholesterol or triglyceride levels. The study appears in JAMA and is being released to coincide with its presentation at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions 2014.

The World Health Organization estimates that annual global mortality ...

DALLAS - November 17, 2014 - Using next generation gene sequencing techniques, cancer researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have identified more than 3,000 new mutations involved in certain kidney cancers, findings that help explain the diversity of cancer behaviors.

"These studies, which were performed in collaboration with Genentech Inc., identify novel therapeutic targets and suggest that predisposition to kidney cancer across species may be explained, at least in part, by the location of tumor suppressor genes with respect to one another in the genome," said ...

Washington, D.C.--Silicon is the second most-abundant element in the earth's crust. When purified, it takes on a diamond structure, which is essential to modern electronic devices--carbon is to biology as silicon is to technology. A team of Carnegie scientists led by Timothy Strobel has synthesized an entirely new form of silicon, one that promises even greater future applications. Their work is published in Nature Materials.

Although silicon is incredibly common in today's technology, its so-called indirect band gap semiconducting properties prevent it from being ...

HOUSTON -- (Nov. 17, 2014) - A compound called calcein may act to inhibit topoisomerase IIβ-binding protein 1 (TopBP1), which enhances the growth of tumors, said researchers from Baylor College of Medicine in a report that appears online in the journal Nature Communications.

"The progression of many solid tumors is driven by de-regulation of multiple common pathways," said Dr. Weei-Chin Lin, associate professor of medicine- hematology & oncology, and a member of the NCI-designated Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor. Among those are the retinoblastoma (Rb), PI(3)K/Akt ...

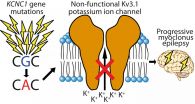

A study led by researchers at University of Helsinki, Finland and Universities of Melbourne and South Australia has identified a new gene for a progressive form of epilepsy. The findings of this international collaborative effort have been published today, 17 November 2014, in Nature Genetics.

Progressive myoclonus epilepsies (PME) are rare, inherited, and usually childhood-onset neurodegenerative diseases whose core symptoms are epileptic seizures and debilitating involuntary muscle twitching (myoclonus). The goal of the international collaborative study was to identify ...

Scientists have found that altering members of the p53 gene family, known as tumor suppressor genes, causes rapid regression of tumors that are deficient in or totally missing p53. Study results suggest existing diabetes drugs, which impact the same gene-protein pathway, might be effective for cancer treatment.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center investigation showed that, in vivo, the genes p63 and p73 can be manipulated to upregulate or increase levels of IAPP, a protein important for the body's ability to metabolize glucose. IAPP is found in some diabetes ...

BALTIMORE, MD - As the world's diminishing fresh water resources are increasing allocated for human use, agricultural and horticultural production operations must rely more often on the use of brackish, saline, or reclaimed water for irrigation. These saline-rich water sources often contain electrical conductivities that can negativity affect plants' ability to thrive. Salinity is particularly problematic for ornamental plants such as daffodils because of the potential for damage to plants' aesthetics and visual qualities.

In the September 2014 issue of HortScience, Maren ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- One of the family of drugs prescribed for rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory conditions is called TNF inhibitors. They act by dampening part of the immune system called tumor necrosis factor (TNF). In one of the balancing acts of medicine, the anti-inflammatory action of the drug also increases the risk for other conditions, in this case, a rare form of eye cancer, uveal melanoma. Mayo Clinic researchers make the case and alert physicians in an article in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Mayo researchers studied three patients -- two women and a ...

Who says your kids don't listen to you?

An Indiana University study has found that setting specific family rules about healthy eating and sedentary behavior actually leads to healthier practices in children.

Data analyzed for the study was originally part of a data set used to evaluate the Wellborn Baptist Foundation's HEROES program, a K-12 school-based obesity prevention initiative set in the Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky tri-state area. However, lead author Alyssa M. Lederer, doctoral candidate and associate instructor in the Department of Applied Health Science ...