(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- Nearly four decades of observations of Tanzanian chimpanzees has revealed that the mothers of sons are about 25 percent more social than the mothers of daughters. Boy moms were found to spend about two hours more per day with other chimpanzees than the girl moms did.

Chimpanzees have a male-dominated society in which rank is a constant struggle and females with infants might face physical violence and even infanticide. It would be safer in general to just avoid groups where aggressive males are present, yet the mothers of sons choose to do so anyway.

"It is really intriguing that the sex of her infant influences the mother's behavior right from birth and that the same female is more social when she has a son than when she has a daughter," said Anne Pusey, chair of Evolutionary Anthropology at Duke.

The researchers believe that the mothers are giving the young males the opportunity to observe males in social situations, even while still clinging to their mothers. This gives the youngsters a start on developing the social skills they'll need to thrive in the competitive world of adults.

The findings are based on an analysis of 37 years of daily observations of East African chimpanzeess from the Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Duke University houses all of the data from the famous Kasekela chimpanzee community in the Jane Goodall Institute Research Center, which contains more than 50 years of observational data all the way back to Jane Goodall's first hand-written observations from the early 1960s.

The data largely consist of "follows," in which a researcher focuses on one chimpanzee and notes her behaviors and interactions with others throughout the day. Duke scholars led by Pusey are now working on digitizing the entire collection of Gombe data in the Goodall archive to enable more longitudinal studies of this kind.

"Drawing from the long-term datasets, we were able to investigate patterns within the same mother, examining how she behaved with her sons versus with her daughters," said lead author Carson Murray, an assistant professor at George Washington University, who was a PhD student under Pusey. "These results are even more compelling than a general pattern, demonstrating that the same female behaves very differently depending on the sex of her offspring."

For this study, researchers measured gregariousness based on three kinds of analyses. They looked at how much time a mother spent with other adults who were not immediate family members; the average size of the mother's party and its composition; and the proportion of time a mother spent in mixed-sex and female-only parties.

For the most part, mothers with offspring spend their time alone or with adult daughters and other dependents. Adult males are the more gregarious sex, forming coalitions with other males to assert rank, defend their territory and hunt as a group.

Mothers with sons were found to spend more time with others and to associate with more of their kin. During the first six months of an infant's life, mothers with sons spend significantly more time in mixed-sex parties than mothers with daughters.

At 30 to 36 months, chimpanzee infants start moving around more on their own without being carried and spend most of their time out of mother's reach. At this age, the male infants start having more interactions with unrelated chimpanzees, especially adult males. Their female counterparts are significantly less social.

As the offspring get older and range further from their mothers, the young males have more social partners over the course of the day. Juvenile and adolescent males watch their adult counterparts carefully and often mimic the behaviors they see, including charging displays and copulation.

"Mothers obviously increase social exposure for their young male infants," Murray said. "This finding leads to a larger question about how social exposure might shape gender-typical behavior in humans as well."

This study also suggests it is possible the sons themselves are driving the increased gregariousness later in life. In early infancy, the boy mothers spend about the same time in female-only groups that the girl moms do. But as their sons become older, boy moms spend more time in female-only, nursery groups, probably because the young males are attracted to the offspring of other females as playmates.

"One of the most surprising results to me was that mothers with young females still have lower association with their relatives," Murray said. "As we argue in the paper, this suggests that social exposure is less critical to females in general."

Social exposure has a potential downside too. Females with low rank are known to experience more social stress in large groups, and there is always a risk of infanticide against the young chimpanzees. Perhaps the best way to avoid having infants killed is to steer clear of groups, which the mothers do up to 70 percent of the time.

"Mothers with infant daughters were likely to be avoiding competitive and stressful situations," Murray said. "While mothers with sons seem willing to incur those costs for the benefit of having their sons socialized."

INFORMATION:

To learn more about the Jane Goodall Institute Research Center: http://evolutionaryanthropology.duke.edu/research/anne-pusey-lab

Data digitization was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants (R00HD057992 and R01 AI050529); National Science Foundation Grants (DBS-9021946, SBR-9319909, BCS-0452315, and LTREB-1052693); the Harris Steel Group; the Windibrow Foundation; the Carnegie Corporation; the University of Minnesota; Duke University; the Leo S. Guthman Foundation; and the National Geographic Society. Two GWU researchers were supported by a departmental grant from NSF (DGE-0801634). Behavioral analyses were supported by National Institutes of Health (R00HD057992).

CITATION: "Early Social Exposure in Wild Chimpanzees: Mothers with Sons are More Gregarious than Mothers with Daughters," Carson Murray, Elizabeth Lonsdorf, Margaret Stanton, Kaitlin Wellens, Jordan Miller, Jane Goodall, Anne Pusey. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Nov. 24, 2014. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1409507111

A National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded research team has successfully tested an autonomous underwater vehicle, AUV, that can produce high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of Antarctic sea ice. SeaBED, as the vehicle is known, measured and mapped the underside of sea-ice floes in three areas off the Antarctic Peninsula that were previously inaccessible.

The results of the research were published this week in the journal Nature Geoscience. Scientists at the Institute of Antarctic and Marine Science (Australia), Antarctic Climate and Ecosystem Cooperative Research ...

Coral reefs persist in a balance between reef construction and reef breakdown. As corals grow, they construct the complex calcium carbonate framework that provides habitat for fish and other reef organisms. Simultaneously, bioeroders, such as parrotfish and boring marine worms, breakdown the reef structure into rubble and the sand that nourishes our beaches. For reefs to persist, rates of reef construction must exceed reef breakdown. This balance is threatened by increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, which causes ocean acidification (decreasing ocean pH). Prior research ...

LIND, Wash. - In the world's driest rainfed wheat region, Washington State University researchers have identified summer fallow management practices that can make all the difference for farmers, water and soil conservation, and air quality.

Wheat growers in the Horse Heaven Hills of south-central Washington farm with an average of 6-8 inches of rain a year. Wind erosion has caused blowing dust that exceeded federal air quality standards 20 times in the past 10 years.

"Some of these events caused complete brown outs, zero visibility, closed freeways," said WSU research ...

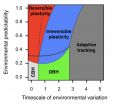

Researchers from North Carolina State University have created a model that mimics how differently adapted populations may respond to rapid climate change. Their findings demonstrate that depending on a population's adaptive strategy, even tiny changes in climate variability can create a "tipping point" that sends the population into extinction.

Carlos Botero, postdoctoral fellow with the Initiative on Biological Complexity and the Southeast Climate Science Center at NC State and assistant professor of biology at Washington State University, wanted to find out how diverse ...

Last year, University of Pennsylvania researchers Alexander J. Stewart and Joshua B. Plotkin published a mathematical explanation for why cooperation and generosity have evolved in nature. Using the classical game theory match-up known as the Prisoner's Dilemma, they found that generous strategies were the only ones that could persist and succeed in a multi-player, iterated version of the game over the long term.

But now they've come out with a somewhat less rosy view of evolution. With a new analysis of the Prisoner's Dilemma played in a large, evolving population, they ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (Nov. 24, 2014, 3 P.M.) -- Researchers at Tufts University, in collaboration with a team at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, have demonstrated a resorbable electronic implant that eliminated bacterial infection in mice by delivering heat to infected tissue when triggered by a remote wireless signal. The silk and magnesium devices then harmlessly dissolved in the test animals. The technique had previously been demonstrated only in vitro. The research is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early ...

A Jackson Laboratory research team has found that the misfolded proteins implicated in several cardiac diseases could be the result not of a mutated gene, but of mistranslations during the "editing" process of protein synthesis.

In 2006 the laboratory JAX Professor and Howard Hughes Medical Investigator Susan Ackerman, Ph.D., showed that the movement disorders in a mouse model with a mutation called sti (for "sticky," referring to the appearance of the animal's fur) were due to malformed proteins resulting from the incorporation of the wrong amino acids into proteins ...

Research that provides a new understanding of how bacterial toxins target human cells is set to have major implications for the development of novel drugs and treatment strategies.

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) are toxins produced by major bacterial pathogens, most notably Streptococcus pneumoniae and group A streptococci, which collectively kill millions of people each year.

The toxins were thought to work by interacting with cholesterol in target cell membranes, forming pores that bring about cell death.

Published today in the prestigious journal Proceedings ...

A commonly prescribed muscle relaxant may be an effective treatment for a rare but devastating form of diabetes, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report.

The drug, dantrolene, prevents the destruction of insulin-producing beta cells both in animal models of Wolfram syndrome and in cell models derived from patients who have the illness.

Results are published Nov. 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Online Early Edition.

Patients with Wolfram syndrome typically develop type 1 diabetes as very young children ...

(Edmonton) A team of researchers from the University of Alberta has discovered a new approach to fighting breast and thyroid cancers by targeting an enzyme they say is the culprit for the "vicious cycle" of tumour growth, spread and resistance to treatment.

A team led by University of Alberta biochemistry professor David Brindley found that inhibiting the activity of an enzyme called autotaxin decreases early tumour growth in the breast by up to 70 per cent. It also cuts the spread of the tumour to other parts of the body (metastasis) by a similar margin. Autotaxin is ...