(Press-News.org) A team of scientists has revealed how certain harmful bacteria drill into our cells to kill them. Their study shows how bacterial 'nanodrills' assemble themselves on the outer surfaces of our cells, and includes the first movie of how they then punch holes in the cells' outer membranes. The research, published today in the journal eLife, supports the development of new drugs that target this mechanism, which is implicated in serious diseases. The team brings together researchers from UCL, Birkbeck, University of London, the University of Leicester, and Monash University (Melbourne).

Unlike drills from a DIY kit, which twist and grind their way through a surface, bacterial nanodrills do not contain rotating parts. Rather, they are ring-like structures (similar to an eyelet) built out of self-assembling toxin molecules. Once assembled, the toxins deploy a blade around the ring's inside edge that slices down into the cell membrane, forming a hole.

To determine how these rings are built, team member Natalya Dudkina made several thousand images of artificial cell membranes coated with toxins, using an electron microscope. Dudkina is a member of Helen Saibil's group at Birkbeck, University of London, which specialises in mapping biological structures using electron microscopy.

"Each ring was formed of around 37 copies of the toxin molecule. But aside from complete rings, we also observed arc-shaped, incomplete rings," Dudkina said. "One problem we had, though, was that our method can only record snapshots of the membrane perforation process frozen at different intermediate stages."

The solution to this was to produce a 'movie' of what happens when the toxins are placed on a cell membrane. This was carried out with atomic force microscopy (AFM) at Bart Hoogenboom's lab at the London Centre for Nanotechnology at UCL. AFM uses an ultrafine needle to feel, rather than see, a surface. This needle repeatedly scans the surface to produce a moving image that refreshes fast enough to show how the toxins move over the membrane and then cut holes in the membrane as they sink in.

"It was quite spectacular to look at," said Carl Leung, a member of Hoogenboom's lab at UCL. "After the initial assembly of the toxins into arcs and rings, they kept skating over the membrane surface. Then they stopped, sank into the membrane, and started spitting out the material they had drilled through, like sawdust when you drill holes in wood."

A big surprise for the team was that complete rings aren't needed to pierce the cell membrane: even relatively short fragments are still able to cut holes, albeit smaller ones, and hold them open, allowing bacteria to feed on the cell's contents.

Together, these findings give a detailed view of how these bacterial toxins drill holes in cell membranes. The snapshots from the electron microscopy show how the rings are structured at the start and the end of the drilling process, and the moving images from the AFM show the process as it unfolds.

The discovery supports the development of new drugs that can target bacterial nanodrills and help treat the diseases in which they are implicated. These include pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia. Extensive research into such drugs that is ongoing at the University of Leicester, which also provided a genetically modified form of the toxin to help identify the different steps in the hole-drilling process.

INFORMATION:

Notes for Editors

For a copy of the paper, images, video or to speak to Professor Bart Hoogenboom or Carl Leung please contact Siobhan Pipa in the UCL press office, T: +44 (0)207 679 9041, E: siobhan.pipa@ucl.ac.uk

To speak to Natalya Dudkina please contact Bryony Merritt in the Birkbeck press office on T: +44 (0)20 7380 3133, E: b.merritt@bbk.ac.uk

To speak to the researchers at the University of Leicester please contact Ather Mirza in the University of Leicester News Centre on T: +44 (0)116 252 3335, E: pressoffice@le.ac.uk

Images of the process and a video are available on request.

University College London

Founded in 1826, UCL was the first English university established after Oxford and Cambridge, the first to admit students regardless of race, class, religion or gender, and the first to provide systematic teaching of law, architecture and medicine. We are among the world's top universities, as reflected by performance in a range of international rankings and tables. UCL currently has almost 29,000 students from 150 countries and in the region of 10,000 employees. Our annual income is more than £900 million.

http://www.ucl.ac.uk | Follow us on Twitter @uclnews | Watch our YouTube channel YouTube.com/UCLTV

University of Leicester

The University of Leicester is a leading UK University committed to international excellence through the creation of world changing research and high quality, inspirational teaching. Leicester is consistently one of the most socially inclusive of the UK's top 20 universities with a long-standing commitment to providing fairer and equal access to higher education. Leicester is a three-time winner of the Queen's Anniversary Prize for Higher and Further Education and is the only University to win seven consecutive awards from the Times Higher. Leicester is ranked among the top one per-cent of universities in the world by the THE World University Rankings.

Birkbeck

Birkbeck is a world-class research and teaching institution, a vibrant centre of academic excellence and London's only specialist provider of evening higher education. We encourage applications from students without traditional qualifications and we have a wide range of programmes to suit every entry level. 18,000 students study with us every year. They join a community that is as diverse and cosmopolitan as London's population.

In the city that never sleeps, it's easy to overlook the insects underfoot. But that doesn't mean they're not working hard. A new study from North Carolina State University shows that insects and other arthropods play a significant role in disposing of garbage on the streets of Manhattan.

"We calculate that the arthropods on medians down the Broadway/West St. corridor alone could consume more than 2,100 pounds of discarded junk food, the equivalent of 60,000 hot dogs, every year - assuming they take a break in the winter," says Dr. Elsa Youngsteadt, a research associate ...

ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, Ill. (December 2, 2014) - If you are one of the millions of Americans who experiences a severe allergic reaction to food, latex or an insect sting, you should know the first line of defense in combating the reaction is epinephrine. Unfortunately, not all medical personnel know how important epinephrine is in bringing an allergic reaction under control.

According to new guidelines published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the scientific publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), the fast administration ...

AUSTIN, Texas -- Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have identified a network of genes that appear to work together in determining alcohol dependence. The findings, which could lead to future treatments and therapies for alcoholics and possibly help doctors screen for alcoholism, are being published this week in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

By comparing patterns of genetic code from the brain tissue of alcoholics and nonalcoholics, the researchers discovered a particular set of genes co-expressed together in the individuals who had consumed the most ...

CHICAGO - According to a new long-term study, diabetic patients with even mild coronary artery disease face the same relative risk for a heart attack or other major adverse heart events as diabetics with serious single-vessel obstructive disease. Results of the study were presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Researchers at the University of British Columbia and St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver analyzed data from the Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation For Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter (CONFIRM) Registry, ...

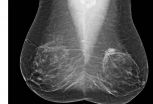

CHICAGO - A major new study being presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) has found that digital breast tomosynthesis, also known as 3-D mammography, has the potential to significantly increase the cancer detection rate in mammography screening of women with dense breasts.

Breasts are considered dense if they have a lot of fibrous or glandular tissue but not much fatty tissue. Research has shown that dense breasts are more likely to develop cancer, a problem compounded by the fact that cancer in dense breasts can be difficult ...

CHICAGO - A study of breast cancers detected with screening mammography found that strong family history and dense breast tissue were commonly absent in women between the ages of 40 and 49 diagnosed with breast cancer. Results of the study were presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

"Screening recommendations for this age group continue to be debated," said Bonnie N. Joe, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in residence and chief of women's imaging at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). "Recent publications ...

CHICAGO - Patients value direct, independent access to their medical exams, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Fragmentation of health information among physicians, healthcare institutions or practices, and inefficient exchange of test results can decrease quality of care and contribute to high medical costs. Improving communications and giving patients more control over their care are critical goals of health IT initiatives.

"Easy and timely electronic access to an online unified source of ...

Disparities in mental-health treatment are known to be associated with patients' racial and ethnic backgrounds. Now, a large study by researchers with UC Davis has found one possible reason for those disparities: Some racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to be assessed and referred for treatment by their medical providers.

The study of more than 9,000 diverse individuals, including Latinos, African-Americans, Asian-Americans and non-Hispanic whites, found that patients of different racial and ethnic backgrounds reported experiencing differing treatment approaches ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Patients with head and neck cancer who used antacid medicines to control acid reflux had better overall survival, according to a new study from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Reflux can be a common side effect of chemotherapy or radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. Doctors at the University of Michigan frequently prescribe two types of antacids - proton pump inhibitors or histamine 2 blockers - to help treat this side effect.

The researchers looked at 596 patients who were treated for head and neck cancer. More than ...

Sons whose fathers have criminal records tend to have lower cognitive abilities than sons whose fathers have no criminal history, data from over 1 million Swedish men show. The research, conducted by scientists in Sweden and Finland, indicates that the link is not directly caused by fathers' behavior but is instead explained by genetic factors that are shared by father and son.

The study is published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"The findings are important because cognitive ability is among the most important psychological ...