Study set to shape medical genetics in Africa

First comprehensive characterization of genetic diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa published

2014-12-03

(Press-News.org) Researchers from the African Genome Variation Project (AGVP) have published the first attempt to comprehensively characterise genetic diversity across Sub-Saharan Africa. The study of the world's most genetically diverse region will provide an invaluable resource for medical researchers and provides insights into population movements over thousands of years of African history. These findings appear in the journal Nature.

"Although many studies have focused on studying genetic risk factors for disease in European populations, this is an understudied area in Africa," says Dr Deepti Gurdasani, lead author on the study and a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. "Infectious and non-infectious diseases are highly prevalent in Africa and the risk factors for these diseases may be very different from those in European populations."

"Given the evolutionary history of many African populations, we expect them to be genetically more diverse than Europeans and other populations. However we know little about the nature and extent of this diversity and we need to understand this to identify genetic risk factors for disease."

Dr Manjinder Sandhu and colleagues collected genetic data from more than 1800 people - including 320 whole genome sequences from seven populations - to create a detailed characterisation of 18 ethnolinguistic groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. Genetic samples were collected through partnerships with doctors and researchers in Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda.

The AGVP investigators, who are funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK Medical Research Council, found 30 million genetic variants in the seven sequenced populations, a fourth of which have not previously been identified in any population group. The authors show that in spite of this genetic diversity, it is possible to design new methods and tools to help understand this genetic variation and identify genetic risk factors for disease in Africa.

"The primary aim of the AGVP is to facilitate medical genetic research in Africa. We envisage that data from this project will provide a global resource for researchers, as well as facilitate genetic work in Africa, including those participating in the recently established pan-African Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) genomic initiative," says Dr Charles Rotimi, senior author from the Centre for Research on Genomics and Global Health, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

The authors also found evidence of extensive European or Middle Eastern genetic ancestry among several populations across Africa. These date back to 9,000 years ago in West Africa, supporting the hypothesis that Europeans may have migrated back to Africa during this period. Several of the populations studied are descended from the Bantu, a population of agriculturists and pastoralists thought to have expanded across large parts of Africa around 5,000 years ago.

The authors found that several hunter-gatherer lines joined the Bantu populations at different points in time in different parts of the continent. This provides important insights into hunter-gatherer populations that may have existed in Africa prior to the Bantu expansion. It also means that future genetic research may require a better understanding of this hunter-gatherer ancestry.

"The AGVP has provided interesting clues about ancient populations in Africa that pre-dated the Bantu expansion," says Dr Manjinder Sandhu, lead senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK and the Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge. "To better understand the genetic landscape of ancient Africa we will need to study modern genetic sequences from previously under-studied African populations, along with ancient DNA from archaeological sources."

The study also provides interesting clues about possible genetic loci associated with increased susceptibility to high blood pressure and various infectious diseases, including malaria, Lassa fever and trypanosomiasis, all highly prevalent in some regions of Africa. These genetic variants seem to occur with different frequencies in disease endemic and non-endemic regions, suggesting that this may have occurred in response to the different environments these populations have been exposed to over time.

"The AGVP has substantially expanded on our understanding of African genome variation. It provides the first practical framework for genetic research in Africa and will be an invaluable resource for researchers across the world. In collaboration with research groups across Africa, we hope to extend this resource with large-scale sequencing studies in more of these diverse populations," says Dr Sandhu.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-12-03

ROSEMONT, Ill.--Compression fractures in the spine due to osteoporosis, a common condition causing progressive bone loss and increased fracture risk, are especially common in older women. A new study appearing in the December 3rd issue of the Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery (JBJS) found that patients who wore a brace as treatment for a spinal compression fracture had comparable outcomes in terms of pain, function and healing when compared to patients who did not wear a brace.

Nearly 700,000 men and women suffer from a spinal compression fracture each year. These fractures, ...

2014-12-03

People who work around the clock could actually be setting themselves back, according to Virginia Tech biologists.

Researchers found that a protein responsible for regulating the body's sleep cycle, or circadian rhythm, also protects the body from developing sporadic forms of cancers.

"The protein, known as human period 2, has impaired function in the cell when environmental factors, including sleep cycle disruption, are altered," said Carla Finkielstein, an associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science, Fralin Life Science Institute affiliate, ...

2014-12-03

The more time you spend getting to and from work, the less likely you are to be satisfied with life, says a new Waterloo study.

Published in World Leisure Journal, the research reveals exactly why commuting is such a contentment killer--and surprisingly, traffic isn't the only reason to blame.

"We found that the longer it takes someone to get to work, the lower their satisfaction with life in general," says Margo Hilbrecht, a professor in Applied Health Sciences and the associate director of research for the Canadian Index of Wellbeing.

While commuting has long been ...

2014-12-03

Is your inbox burning you out? Then take heart - research from the University of British Columbia suggests that easing up on email checking can help reduce psychological stress.

Some of the study's 124 adults -- including students, financial analysts medical professionals and others -- were instructed to limit checking email to three times daily for a week. Others were told to check email as often as they could (which turned out to be about the same number of times that they normally checked their email prior to the study).

These instructions were then reversed for ...

2014-12-03

RIVERSIDE, Calif. - Geckos, found in places with warm climates, have fascinated people for hundreds of years. Scientists have been especially intrigued by these lizards, and have studied a variety of features such as the adhesive toe pads on the underside of gecko feet with which geckos attach to surfaces with remarkable strength.

One unanswered question that has captivated researchers is: Is the strength of this adhesion determined by the gecko or is it somehow intrinsic to the adhesive system? In other words, is this adhesion a result of the entire animal initiating ...

2014-12-03

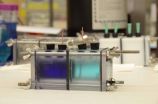

An efficient method to harvest low-grade waste heat as electricity may be possible using reversible ammonia batteries, according to Penn State engineers.

"The use of waste heat for power production would allow additional electricity generation without any added consumption of fossil fuels," said Bruce E. Logan, Evan Pugh Professor and Kappe Professor of Environmental Engineering. "Thermally regenerative batteries are a carbon-neutral way to store and convert waste heat into electricity with potentially lower cost than solid-state devices."

Low-grade waste heat is an ...

2014-12-03

New Rochelle, NY, December 3, 2014--Hereditary angioedema (HAE), a rare genetic disease that causes recurrent swelling under the skin and of the mucosal lining of the gastrointestinal tract and upper airway, usually first appears before 20 years of age. A comprehensive review of the therapies currently available to treat HAE in adults shows that some of these treatments are also safe and effective for use in older children and adolescents. Current and potential future therapies are discussed in a Review article in a special issue of Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology, ...

2014-12-03

Typhoon Hagupit continues to intensify as it continued moving through Micronesia on Dec. 3 triggering warnings. NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead and captured an image of the strengthening storm while the Rapidscat instrument aboard the International Space Station provided information about the storm's winds.

The International Space Station-RapidScat instrument monitors ocean winds to provide essential measurements used in weather predictions, including hurricanes. "RapidScat measures wind speed and direction over the ocean surface and captured an image of Hagupit ...

2014-12-03

This news release is available in French.

Quebec City, December 3, 2014--Researchers at Université Laval's Faculty of Science and Engineering and Centre for Optics, Photonics and Lasers have developed smart textiles able to monitor and transmit wearers' biomedical information via wireless or cellular networks. This technological breakthrough, described in a recent article in the scientific journal Sensors, clears a path for a host of new developments for people suffering from chronic diseases, elderly people living alone, and even firemen and police officers.

A ...

2014-12-03

Researchers at North Carolina State University have for the first time mapped human disease-causing pathogens, dividing the world into a number of regions where similar diseases occur.

The findings show that the world can be separated into seven regions for vectored human diseases - diseases that are spread by pests, like mosquito-borne malaria - and five regions for non-vectored diseases, like cholera.

Interestingly, not all of the regions are contiguous. The British Isles and many of its former colonies, such as the United States and Australia, have similar diseases ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study set to shape medical genetics in Africa

First comprehensive characterization of genetic diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa published