(Press-News.org) In a breakthrough study to be published on the December 4th issue of the prestigious scientific journal Cell, a research team led by Miguel Soares at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC; Portugal) discovered that specific bacterial components in the human gut microbiota can trigger a natural defense mechanism that is highly protective against malaria transmission.

Over the past few years, the scientific community became aware that humans live under a continuous symbiotic relationship with a vast community of bacteria and other microbes that reside in the gut. These microbes, know as the gut microbiota, do not necessarily cause disease to humans and instead can influence a variety of physiologic functions that are essential to maintain health. Some of these microbes, including specific strains of Escherichia coli (E. coli) that are usual inhabitant of the human gut, express on their surface sugar molecules (known as carbohydrates or glycans). These glycans can be recognized by the human immune system, which results in the production of high levels of circulating natural antibodies in adult individuals. It has been speculated that natural antibodies directed against sugar molecules expressed by the microbiota may also recognize perhaps similar sugar molecules expressed by pathogens, that is, parasites that can cause diseases in humans.

Bahtiyar Yilmaz, a PhD student of the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência PhD programme in Miguel Soares' laboratory, found that the Plasmodium parasite, the causative agent of malaria, expresses a sugar molecule called alpha-gal, which is also expressed at the surface of a strain of E. coli that is part of the human gut microbiota. In a series of experiments performed in mice, Bahtiyar Yilmaz went on to find that expression of alpha-gal by these bacteria, when resident in the gut, is sufficient to induce the production of natural antibodies that can recognize the same sugar molecule when expressed at the surface of Plasmodium parasites. He then found that these antibodies attach to the alpha-gal sugar at the surface of Plasmodium parasites, immediately after the inoculation in the skin by a mosquito, the vector of malaria transmission. When this occurs the anti-alpha-gal antibodies activate an additional arm of the human immune system, called the complement cascade, which goes on to punch holes and kills the Plasmodium parasite before it can move out of the skin. The protective effect is such that when present at high levels at the time of the mosquito bite, anti-alpha-gal antibodies manage to arrest the transition of the parasite from the skin into the blood stream and by doing so block malaria transmission.

It was well established before these studies, that only a fraction of all adult individuals that are confronted to the bite of mosquitoes in endemic areas of malaria do become infected by the Plasmodium parasite and eventually go on to contract malaria. This argued that adults might have a natural defense mechanism against malaria transmission, which is in sharp contrast with children under 3-5 years old that are much more susceptible to contract malaria. When analyzing individuals from an endemic area of malaria in Mali, in collaboration with a research team lead by Peter D. Crompton at National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Maryland; USA) and at the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako (Bamako, Mali), the research team lead by Miguel Soares established that those individuals that have the lowest levels of circulating anti-alpha-gal antibodies are also those that are the most susceptible to contract malaria. In contrast those individuals that have the highest levels of circulating anti-alpha-gal antibodies are less susceptible to be infected and to develop malaria. They conclude that the reason why young infants are so susceptible to contract malaria is probably due to the fact that they have not yet generated sufficient levels of circulating natural antibodies directed against the alpha-gal sugar molecule.

With the goal of overcoming this shortcoming, Bahtiyar Yilmaz found that when mice are vaccinated against a synthetic form of alpha-gal that is rather easy and inexpensive to produce, they produced high levels of circulating anti-alpha-gal antibodies that are highly protective against malaria transmission by mosquitoes. Whether the same "trick" can be applied to humans and in particular to young infants to confer protection against malaria transmission is a "burning question" that remains to be answered.

It is estimated that 3.4 billion people are at risk of contracting malaria and WHO data from 2012 reveal that about 460 000 African children died from malaria before reaching their fifth birthday. The present study argues that if one can induce the production of antibodies against alpha-gal in those children one may be able to revert these grim numbers.

Miguel Soares adds: "We observed that children under 3 years old do not have sufficient levels of circulating anti-alpha-gal antibodies, which might be one of the reasons for their exquisite susceptibility to malaria. One of the beauties of the protective mechanism we just discovered is that it can be induced via a standard vaccination protocol, leading to the production of high levels of anti-alpha-gal antibodies that bind and kill the Plasmodium parasite. If we can vaccinate these young children against alpha-gal, many lives might be saved."

INFORMATION:

This study was carried out at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (Oeiras, Portugal) in collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Maryland; USA), Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical (Lisbon, Portugal), St Vincent's Hospital and University of Melbourne (Victoria, Australia), University of Chicago (Chicago, USA), and the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako (Bamako, Mali).

Bahtiyar Yilmaz, Silvia Portugal, Tuan M. Tran, Raffaella Gozzelino, Susana Ramos, Joana Gomes, Ana Regalado, Peter J. Cowan, Anthony J.F. d'Apice, Anita S. Chong, Ogobara K. Doumbo, Boubacar Traore, Peter D. Crompton, Henrique Silveira, and Miguel P. Soares. (2014). Gut Microbiota Elicits a Protective Immune Response against Malaria Transmission. Cell 159.

Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.053

This discovery has a potential application in the treatment of certain blood disorders for which there is currently no cure. The study was led by Dr. Simón Méndez-Ferrer of the CNIC, working in partnership with the laboratories of Doctors Jürg Schwaller and Radek Skoda of the University Hospital in Basel (Switzerland). The study's authors have demonstrated in mice that tamoxifen, a drug already approved and widely used for the treatment of breast cancer, blocks the symptoms and the progression of a specific group of blood disorders known as myeloproliferative ...

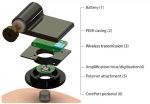

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- In a study in the journal Neuron, scientists describe a new high data-rate, low-power wireless brain sensor. The technology is designed to enable neuroscience research that cannot be accomplished with current sensors that tether subjects with cabled connections.

Experiments in the paper confirm that new capability. The results show that the technology transmitted rich, neuroscientifically meaningful signals from animal models as they slept and woke or exercised.

"We view this as a platform device for tapping into the richness of ...

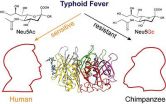

The bacterium Salmonella Typhi causes typhoid fever in humans, but leaves other mammals unaffected. Researchers at University of California, San Diego and Yale University Schools of Medicine now offer one explanation -- CMAH, an enzyme that humans lack. Without this enzyme, a toxin deployed by the bacteria is much better able to bind and enter human cells, making us sick. The study is published in the Dec. 4 issue of Cell.

In most mammals (including our closest evolutionary cousins, the great apes), the CMAH enzyme reconfigures the sugar molecules found on these animals' ...

The link between obesity and cardiovascular diseases is well acknowledged. Being obese or overweight is a major risk factor for the development of elevated blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. But it has net been known how obesity increases the risk of high blood pressure, making it difficult to develop evidence based therapies for obesity, hypertension and heart disease.

In a ground-breaking study, published today in the prestigious journal, Cell (embargo midday EST), researchers from Monash University in Australia, Warwick, Cambridge in the UK and several American ...

Leptin, a hormone that regulates the amount of fat stored in the body, also drives the increase in blood pressure that occurs with weight gain, according to researchers from Monash University and the University of Cambridge.

Being obese or overweight is a major risk factor for the development of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Whilst a number of factors may be involved, the precise explanation for the link between these two conditions has been unclear.

In a study published today in the journal Cell, a research team led by Professor Michael Cowley, ...

PHILADELPHIA--People with mental illness are more likely to have been tested for HIV than those without mental illness, according to a new study from a team of researchers at Penn Medicine and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published online this week in AIDS Patient Care and STDs. The researchers also found that the most seriously ill - those with schizophrenia and bipolar disease - had the highest rate of HIV testing.

The study assessed nationally representative data from 21,785 adult respondents from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Take two poisonous mushrooms, and call me in the morning. While no doctor would ever write this prescription, toxic fungi may hold the secrets to tackling deadly diseases.

A team of Michigan State University scientists has discovered an enzyme that is the key to the lethal potency of poisonous mushrooms. The results, published in the current issue of the journal Chemistry and Biology, reveal the enzyme's ability to create the mushroom's molecules that harbor missile-like proficiency in attacking and annihilating a single vulnerable target in the ...

Some National Football League (NFL) players have been seeking out unproven stem cell therapies to help accelerate recoveries from injuries, according to a new paper from Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy. While most players seem to receive treatment within the United States, several have traveled abroad for therapies unavailable domestically and may be unaware of the risks involved, the paper found.

The paper is published in the 2014 World Stem Cell Report, which is a special supplement to the journal Stem Cells and Development and is the official publication ...

Today's smartphones are designed to entertain and are increasingly marketed to young adults as leisure devices. Not surprisingly, research suggests that young adults most often use their phones for entertainment purposes rather than for school or work.

With this in mind, three Kent State University researchers, Andrew Lepp, Ph.D., Jacob Barkley, Ph.D. and Jian Li, Ph.D., and a Kent State graduate student, Saba Salehi-Esfahani, surveyed a random sample of 454 college students to examine how different types of cell phone users experience daily leisure.

The trio from ...

Boston, MA - A study published this week in Genetics in Medicine is the first to explore new parents' attitudes toward newborn genomic testing. The findings suggest that if newborn genomic testing becomes available, there would be robust interest among new parents, regardless of their demographic background.

The study, led by researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Boston Children's Hospital, found that the majority of parents surveyed were interested in newborn genomic testing.

As next-generation whole-exome and genome sequencing is integrated into clinical ...