INFORMATION:

Development of a Novel, Physiologically and Anatomically Realistic in vitro Pediatric Blood Brain Barrier on a Chip

S.P. Deosarkar1, B. Augelli2, B. Prabhakarpandian3, B. Krynska2,4, M.F. Kiani1; 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, Temple University (PA), Philadelphia, PA, 2Department of Neurology, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, 3Biomedical Technology, CFD Research Corporation, Huntsville, AL, 4Shriners Hospitals Pediatric Research Center, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Contact: Sudhir Deosarkar, sudhir.deosarkar@temple.edu

Author presents at ASCB/IFCB:

Poster Session: Engineering Tissues and Organs Monday, December 8 Board 1026 Presentation 1525 Time: 1:30--3:00 pm

Media Contacts:

John Fleischman

jfleischman@ascb.org

513.706-0212 (mobile)

Carol Blymire

carol@carolblymire.com

301.332.8090 (mobile)

Blood brain barrier on a chip could stand in for children in pediatric brain research

2014-12-05

(Press-News.org) In the human brain, the BBB is not the Better Business Bureau but the blood brain barrier and the BBB is serious business in human physiology. The human BBB separates circulating blood from the central nervous system, thus protecting the brain from many infections and toxins. But the BBB also blocks the passage of many potentially useful drugs to the brain and it has long stymied scientists who want to learn more about this vital tissue because of the lack of realistic non-human lab models. Even less is known about the BBB in children. There are significant structural and functional differences between the pediatric and adult BBB, but ethical considerations clearly limit research possibilities. So while it is known that the immature brain is especially vulnerable to damage from inflammation as well as from oxygen or blood deprivation, and an altered BBB has been linked to cerebral palsy and to complications from traumatic brain injury in children, research to date on these questions has been hampered. Now bioengineering researchers at Temple University in Philadelphia have come up with an experimental workaround--a synthetic pediatric blood-brain barrier on a small chip--and have tested it successfully using rat brain endothelial cells (RBECs) from rat pups and human endothelial cells. They will describe it at the ASCB/IFCB meeting in Philadelphia on December 8.

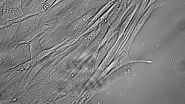

The model BBB on a chip is the creation of postdoctoral fellow Sudhir Deosarkar in the laboratory of Mohammad Kiani at Temple University in Philadelphia in collaboration with Barbara Krynska from the Shriners Hospitals Pediatric Research Center at Temple's School of Medicine and Balabhaskar Prabhakarpandian from CFD Research Corporation in Huntsville, Alabama. Deosarkar calls his physiologically realistic in vitro pediatric BBB model on a chip, the B3C. It has two compartments, one to grow blood vessel cells in and another for cultured brain cells, mimicking the physiology of the BBB. The researchers fabricated the B3C using an optically clear, oxygen permeable polymer, polydimethylsiloxane, on a glass slide with vascular (apical) and tissue (basolateral) compartments. For a proof of principle test, Deosarkar grew the rat brain blood vessel cells on the vascular side of the chip and tested the barrier they formed under a variety of flow conditions with a range of tests including immunofluorescence staining of tight junctions that interconnected the endothelial cells as well as the electrical resistance across the barrier, and by tracking various sized molecules as they crossed to the tissue side of the model.

The results were encouraging, Deosarkar reports. Because the interactions of endothelial cells with adjacent brain cells and factors secreted from these cells are necessary for BBB function, permeability of fluorescently tagged molecules was significantly reduced in the presence of factors from brain cells, modeling the of human BBB. By culturing RBECs and human endothelial cells under flow conditions, the researchers found that cell-cell junctions they formed accurately mimicked endothelial barrier formation in the brain. Says Deosarkar, "In this study, we have developed a first realistic pediatric BBB model (B3C) using RBECs from rat pups and human endothelial cells which could serve as an in vitro model system for studying BBB function in pediatric neurological diseases as well as for testing novel therapies for these diseases."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Alzheimer's in a Dish' model induces skin cells into neurons expressing amyloid-beta

2014-12-05

VIDEO:

This 19-second time lapse video shows the first six hours of neuronal conversion of skin fibroblasts from a patient with Alzheimer's disease.

Click here for more information.

The search for a living laboratory model of human neurons in the grip of Alzheimer's disease (AD)--the so-called "Alzheimer's in a dish"--has a new candidate. In work presented at the ASCB/IFCB meeting in Philadelphia, Håkan Toresson and colleagues at Lund University in Sweden report success ...

Screening for matrix effect in leukemia subtypes could sharpen chemotherapy targeting

2014-12-05

Location, location, location goes the old real estate proverb but cancer also responds to its neighborhood, particularly in the physical surroundings of bone marrow cells where human myeloid leukemias arise and where, according to two Harvard bioengineers, stiffness in the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) can predict how cancer subtypes react to chemotherapy. Correcting for the matrix effect could give oncologists a new tool for matching drugs to patients, the researchers say.

In work to be presented at the ASCB/IFCB meeting in Philadelphia, Jae-Won Shin and David ...

Rescuing the Golgi puts brakes on Alzheimer's progression

2014-12-05

Alzheimer's disease (AD) progresses inside the brain in a rising storm of cellular chaos as deposits of the toxic protein, amyloid-beta (Aβ), overwhelm neurons. An apparent side effect of accumulating Aβ in neurons is the fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus, the part of the cell involved in packaging and sorting protein cargo including the precursor of Aβ. But is the destruction the Golgi a kind of collateral damage from the Aβ storm or is the loss of Golgi function itself part of the driving force behind Alzheimer's? This was the question for Yanzhuang ...

Gravity: It's the law, even for cells

2014-12-05

VIDEO:

Nucleoli (green), small liquid-like nuclear bodies, are kept small and afloat by a fine actin mesh. When the mesh breaks, the nucleoli quickly being to fall and coalesce into larger...

Click here for more information.

Everybody knows that cells are microscopic, but why? Why aren't cells bigger? The average animal cell is 10 microns across and the traditional explanation has been cells are the perfect size because if they were any bigger it would be difficult to get enough ...

Light switchable proteins and superresolution reveal moving protein complexes

2014-12-05

Cells are restless. They move during embryogenesis, tissue repair, regeneration, chemotaxis. Even in disease, tumor metastasis, cells get around. To do this, they have to keep reorganizing their cytoskeleton, removing pieces from one end of a microtubule and adding them to the front, like a railroad with a limited supply of tracks. The EB family of proteins helps regulate this process and can act as a scaffold for other proteins involved in pushing the microtubule chain forward.

Still, how these EB proteins function in space and time has remained a mystery. Now Peng ...

The antioxidant capacity of orange juice is multiplied tenfold

2014-12-05

The antioxidant activity of citrus juices and other foods is undervalued. A new technique developed by researchers from the University of Granada for measuring this property generates values that are ten times higher than those indicated by current analysis methods. The results suggest that tables on the antioxidant capacities of food products that dieticians and health authorities use must be revised.

Orange juice and juices from other citrus fruits are considered healthy due to their high content of antioxidants, which help to reduce harmful free radicals in our body, ...

Penicillin tactics revealed

2014-12-05

Penicillin, the wonder drug discovered in 1928, works in ways that are still mysterious almost a century later. One of the oldest and most widely used antibiotics, it attacks enzymes that build the bacterial cell wall, a mesh that surrounds the bacterial membrane and gives the cells their integrity and shape. Once that wall is breached, bacteria die -- allowing us to recover from infection.

That would be the end of the story, if resistance to penicillin and other antibiotics hadn't emerged over recent decades as a serious threat to human health. While scientists continue ...

Stick out your tongue

2014-12-05

Physicians often ask their patients to "Please stick out your tongue". The tongue can betray signs of illness, which combined with other symptoms such as a cough, fever, presence of jaundice, headache or bowel habits, can help the physician offer a diagnosis. For people in remote areas who do not have ready access to a physician, a new diagnostic system is reported in the International Journal of Biomedical Engineering and Technology that works to combine the soft inputs of described symptoms with a digital analysis of an image of the patient's tongue.

Karthik Ramamurthy ...

IRCM researchers identify a protein that controls the 'guardian of the genome'

2014-12-05

Montréal, December 5, 2014 - A new study published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) sheds new light on a well-known mechanism required for the immune response. Researchers at the IRCM, led by Tarik Möröy, PhD, identified a protein that controls the activity of the p53 tumour suppressor protein known as the "guardian of the genome".

The researchers study the development of T cells and B cells, which are lymphocytes (or immune cells) that play a central role in protecting our ...

Drugs in the environment affect plant growth

2014-12-05

The drugs we release into the environment are likely to have a significant impact on plant growth, a new study has revelealed.

By assessing the impacts of a range of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, researchers at the University of Exeter Medical School and Plymouth University have shown that the growth of edible crops can be affected by these chemicals - even at the very low concentrations found in the environment.

Published in the Journal of Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, the research focused its analysis on lettuce and radish plants and tested the ...