(Press-News.org) Stem cells in early embryos have unlimited potential; they can become any type of cell, and researchers hope to one day harness this rejuvenating power to heal disease and injury. To do so, they must, among other things, figure out how to reliably arrest stem cells in a Peter Pan-like state of indefinite youth and potential. It's clear the right environment can help accomplish this, acting as a sort of Neverland for stem cells. Only now are scientists beginning to understand how.

New collaborative research between scientists at Rockefeller University and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center offers an explanation: Stem cells can rewire their metabolism to enhance an erasure mechanism that helps them avoid committing to a specific fate; in turn, this improves stem cells' ability to renew themselves.

Experiments described today (December 10) in Nature link metabolism, chemical reactions that turn food into energy and cellular building materials, with changes to how genes are packaged, and, as a result, read. It turns out that by skewing their metabolism to favor a particular product, stem cells can keep their entire genome accessible and so maintain their ability to differentiate into any adult cell.

"All of the principal enzymes charged with modifying DNA as well as DNA-histone protein complexes called chromatin use the products of cellular metabolism to do so. But how specific alterations in metabolic pathways can impact gene expression programs during development and differentiation has remained a mystery," says lead researcher C. David Allis, Joy and Jack Fishman Professor and head of the Laboratory of Chromatin Biology and Epigenetics. "This collaborative effort with Craig Thompson's lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering reveals that the nutrients a stem cell uses, and how it uses them, can contribute to a cell's fate by changing the chromatin landscape and, as a result, influencing gene expression."

These changes are epigenetic, meaning they do not affect genes themselves, instead they alter how DNA is packaged, making it more or less accessible for expression. In this case, researchers were interested in a specific type of epigenetic change: chemical groups, known as methyl groups, that attach to chromatin. Generally, the addition of these methyl groups compacts and silences regions of the genome. To maintain their ability to give rise to any type of cell in the body, stem cells need all of their genome available, and so they must keep methylation in check.

Some epigenetic marks, such as methyl groups, are themselves products of metabolism - metabolites. What's more some other metabolites participate in the reactions that remove methylations, making genes available for expression. After joining the Allis Lab, postdoc Bryce Carey presented an idea that tied these concepts together: "What if in stem cells the changes to chromatin reflect a unique metabolism that helps to drive reactions that help to keep chromatin accessible? This connection would explain how embryonic stem cells are so uniquely poised to activate so much of their genomes," Carey says.

Mouse embryonic stem cells grown in a medium known as 2i are much better at renewing themselves than those grown in the traditional medium containing bovine serum, although researchers don't fully understand why. Carey and co-first author Lydia Finley, a postdoc in Thompson's metabolism-focused lab, compared the metabolism of cells grown in both media.

Carey and Finley first noticed that the 2i cells did not require glutamine, an amino acid most cells need to make the metabolite alpha-ketoglutarate, an important player in a series of metabolic reactions known as the citric acid cycle and a metabolite that had also been previously implicated in regulation of methylations on chromatin. Even without glutamine, however, the 2i cells managed to produce significant amounts of alpha-ketoglutarate.

To their surprise, 2i cells had rewired their metabolism to reduce the breakdown of alpha-ketoglutarate in the citric acid cycle, where an enzyme normally converts alpha-ketoglutarate to succinate to fuel cell growth. This resulted in increased alpha-ketoglutarate to fuel the reactions that erase methyl groups from chromatin.

"Basic chemistry dictates that you can drive a reaction forward by supplying more of the starting material while taking away the product. Since the conversion of alpha-ketoglutarate to succinate is linked to the removal of methylations, an increase in alpha-ketoglutarate and the accompanying decline in succinate may promote a loss of epigenetic marks and, perhaps, more self renewal," Finley says. To test this hypothesis, they added alpha-ketoglutarate to serum-cultured stem cells, and, as expected, made them look and behave like the more renewal-prone 2i cells. They also found they could change the activity of certain stem cell genes by adding alpha-ketoglutarate or shutting down the methyl-removing enzyme that uses it.

"This newly established link between metabolism and stem cell fate improves our understanding of development and regeneration, which may, in turn, bring us a little closer to harnessing stem cells' ability to generate new tissue as a way to, for example, heal spinal cord injuries or cure Type 1 diabetes. It may also add a new dimension to our understanding of cancer, in which differentiated cells erroneously take on stem-cell like properties," Allis says.

INFORMATION:

The dragonfly is a swift and efficient hunter. Once it spots its prey, it takes about half a second to swoop beneath an unsuspecting insect and snatch it from the air. Scientists at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus have used motion-capture techniques to track the details of that chase, and found that a dragonfly's movement is guided by internal models of its own body and the anticipated movement of its prey. Similar internal models are used to guide behavior in humans.

"This highlights the role that internal models play in letting these creatures ...

INDIANAPOLIS -- How do some proteins survive the extreme heat generated when they catalyze reactions that can happen as many as a million times per second? Work by researchers from Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) and the University of California Berkeley published online on Dec. 10 in Nature provides an explosive answer to this important question.

Proteins are essential to the human body, doing the bulk of the work within cells. Proteins are large molecules responsible for the structure, function, and regulation of tissues and organs. Enzymes ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important greenhouse gas that doesn't receive as much notoriety as carbon dioxide or methane, but a new study confirms that atmospheric levels of N2O rose significantly as the Earth came out of the last ice age and addresses the cause.

An international team of scientists analyzed air extracted from bubbles enclosed in ancient polar ice from Taylor Glacier in Antarctica, allowing for the reconstruction of the past atmospheric composition. The analysis documented a 30 percent increase in atmospheric nitrous oxide concentrations ...

In a ground-breaking paper published in Nature, they show that the three protein complexes act in relay to regulate cell division: reactivation of one leads to the second becoming active.

Cells rely on control systems to make sure that each aspect of the cell division cycle occurs in the correct order. Following successful segregation of the genomes in mitosis, each must return to its pre-division state in a process called mitotic exit. Mitotic exit is irreversible for all multicellular organisms. Loss of cell cycle control during this process - leading to unregulated ...

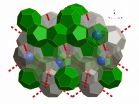

Clathrates are now known to store enormous quantities of methane and other gases in the permafrost as well as in vast sediment layers hundreds of metres deep at the bottom of the ocean floor. Their potential decomposition could therefore have significant consequences for our planet, making an improved understanding of their properties a key priority.

In a paper published in Nature this week, scientists from the University of Göttingen and the Institut Laue Langevin (ILL) report on the first empty clathrate of this type, consisting of a framework of water molecules ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Using a gene-editing system originally developed to delete specific genes, MIT researchers have now shown that they can reliably turn on any gene of their choosing in living cells.

This new application for the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system should allow scientists to more easily determine the function of individual genes, according to Feng Zhang, the W.M. Keck Career Development Professor in Biomedical Engineering in MIT's Departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biological Engineering, and a member of the Broad Institute and MIT's McGovern Institute ...

Anticipated changes in climate will push West Coast marine species from sharks to salmon northward an average of 30 kilometers per decade, shaking up fish communities and shifting fishing grounds, according to a new study published in Progress in Oceanography.

The study suggests that shifting species will likely move into the habitats of other marine life to the north, especially in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea. Some will simultaneously disappear from areas at the southern end of their ranges, especially off Oregon and California.

"As the climate warms, the species ...

For the firefighters and rescue workers conducting the rescue and cleanup operations at Ground Zero from September 2001 to May 2002, exposure to hazardous airborne particles led to a disturbing "WTC cough" -- obstructed airways and inflammatory bronchial hyperactivity -- and acute inflammation of the lungs. At the time, bronchoscopy, the insertion of a fiber optic bronchoscope into the lung, was the only way to obtain lung samples. But this method is highly invasive and impractical for screening large populations.

That motivated Prof. Elizabeth Fireman of Tel Aviv University's ...

There are pros and cons to the support that victimized teenagers get from their friends. Depending on the type of aggression they are exposed to, such support may reduce youth's risk for depressive symptoms. On the other hand, it may make some young people follow the delinquent example of their friends, says a team of researchers from the University of Kansas in the US, led by John Cooley. Their findings are published in Springer's Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

Adolescence is an important time during which youth establish their social identity. ...

Patients with heart disease who receive transfusions during surgeries do just as well with smaller amounts of blood and face no greater risk of dying from other diseases than patients who received more blood, according to a new Rutgers study.

The research, published in the journal Lancet, measures overall mortality and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer and severe infection, and offers new validation to a recent trend toward smaller transfusions.

For the study, led by Jeffrey Carson, chief of the Division of Internal Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson ...