(Press-News.org) Premature ovarian failure, also known as primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), affects 1% of all women worldwide. In most cases, the exact cause of the condition, which is often associated with infertility, is difficult to determine.

A new Tel Aviv University study throws a spotlight on a previously-unidentified cause of POI: a unique mutation in a gene called SYCE1 that has not been previously associated with POI in humans. The research, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, was led by Dr. Liat de Vries and Prof. Lina Basel-Vanagaite of TAU's Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Schneider Children's Medical Center and conducted by a team of researchers from both TAU and Schneider.

While the genes involved in chromosome duplication and division had been shown to cause POI in animal models, this is the first time a similar mutation has been identified in humans.

A new insight

"Researchers know that POI may be associated with Turner's syndrome, a condition in which a woman has only one X chromosome instead of two, or could be due to toxins like chemotherapy and radiation therapy," said Dr. de Vries. "However, in 90% of the cases, the exact cause remains a mystery."

The idea for the study surfaced when Dr. de Vries was asked to treat two POI patients, daughters of two sets of Israeli-Arab parents who were related to each other. The girls presented with typical POI symptoms: one had the appearance of puberty but had not gotten her period, and the other one had not started puberty at all. After ruling out the usual suspects (toxins, autoimmune disease, and known chromosomal and genetic diseases), the researchers set out to identify the genetic cause of POI in the two young women.

"One of my main topics of interest is puberty," said Dr. de Vries. "The clinical presentation of the two sisters, out of 11 children of first-degree cousins, was interesting. In each of the girls, POI was expressed differently. One had reached puberty and was almost fully developed but didn't have menses. The second, 16 years old, showed no signs of development whatsoever."

The researchers performed genotyping in the patients, their parents, and siblings. For this, DNA from the affected sisters was subjected to whole-exome sequencing. Genotyping was also performed in 90 ethnically matched control individuals.

Finding the culprit

The genotyping revealed a mutation that results in nonfunctional protein product in the SYCE1 gene in both affected sisters. The parents and three brothers were found to be carriers of the mutation, and an unaffected sister did not carry the mutation.

"By identifying the genetic mutation, we saved the family a lot of heartache by presenting evidence that any chance of inducing fertility in these two girls is slight," said Dr. de Vries. "As bad as the news is, at least they will not spend years on fertility treatments and will instead invest efforts in acquiring an egg donation, for example. Knowledge is half the battle -- and now the entire family knows it should undergo genetic testing for this mutation."

The researchers are currently investigating evidence of the effects of this genetic mutation on male members of the family. "We are trying to get more family members tested, but it is not always easy in traditional societies. There is still a lot to be done on this subject," said Dr. de Vries.

INFORMATION:

American Friends of Tel Aviv University supports Israel's most influential, most comprehensive, and most sought-after center of higher learning, Tel Aviv University (TAU). US News & World Report's Best Global Universities Rankings rate TAU as #148 in the world, and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings rank TAU Israel's top university. It is one of a handful of elite international universities rated as the best producers of successful startups, and TAU alumni rank #9 in the world for the amount of American venture capital they attract.

A leader in the pan-disciplinary approach to education, TAU is internationally recognized for the scope and groundbreaking nature of its research and scholarship -- attracting world-class faculty and consistently producing cutting-edge work with profound implications for the future.

A new species of short-necked marine reptile from the Triassic period has been discovered in China, according to a study published December 17, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Xiao-hong Chen from Wuhan Centre of China Geological Survey and colleagues.

Hupehsuchia is a group of mysterious Triassic marine reptiles which have, so far, only been found in two counties in Hubei Province, China. The group is known by its modestly long neck, with nine to ten cervical vertebrae, but the authors of this study recently discovered a new species of Hupehsuchia that may ...

A network of nine reference sites off the Australian coast is providing the latest physical, chemical, and biological information to help scientists better understand Australia's coastal seas, according to a study published December 17, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Tim Lynch from CSIRO, Australia and colleagues.

Sustained oceanic observations allow scientists to track changes in oceanography and ecosystems. To address this, the Australian Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) implemented a network of nine National Reference Stations (NRS). The network ...

Like human patients, mice with a form of Duchenne muscular dystrophy undergo progressive muscle degeneration and accumulate connective tissue as they age. Now, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found that the fault may lie at least partly in the stem cells that surround the muscle fibers.

They've found that during the course of the disease, the stem cells become less able to make new muscle and instead begin to express genes involved in the formation of connective tissue. Excess connective tissue -- a condition called fibrosis -- can accumulate ...

Bird migration is an impressive phenomenon, but why birds often travel huge distances to and from their breeding grounds in the far North is still very unclear. Suggestions include that the birds profit from longer daylight hours, or that there are fewer predators. Researchers from the University of Groningen and the NIOO-KNAW Vogeltrekstation, the Dutch centre for bird migration and demographics, have discovered a new explanation.

They investigated barnacle geese breeding on Spitsbergen and compared them with birds of the same species that did not migrate but stayed ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- The best way to protect wild spinner dolphins in Hawaii while also maintaining the local tourism industry that depends on them is through a combination of federal regulations and community-based conservation measures, finds a new study from Duke University.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of tourists to Hawaii pay to have up-close encounters with the animals, swimming with them in shallow bays the dolphins use as safe havens for daytime rest. But as the number of tours increases, so do the pressures they place on the resting dolphins.

The Duke study ...

A new catalytic process is able to convert what was once considered biomass waste into lucrative chemical products that can be used in fragrances, flavorings or to create high-octane fuel for racecars and jets.

A team of researchers from Purdue University's Center for Direct Catalytic Conversion of Biomass to Biofuels, or C3Bio, has developed a process that uses a chemical catalyst and heat to spur reactions that convert lignin into valuable chemical commodities. Lignin is a tough and highly complex molecule that gives the plant cell wall its rigid structure.

Mahdi ...

A close look at the night sky reveals that stars don't like to be alone; instead, they congregate in clusters, in some cases containing as many as several million stars. Until recently, the oldest of these populous star clusters were considered well understood, with the stars in a single group having formed at different times, over periods of more than 300 million years. Yet new research published online today in the journal Nature suggests that the star formation in these clusters is more complex.

Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of researchers at the ...

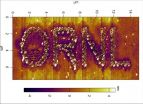

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Dec. 17, 2014--Scientists at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have used advanced microscopy to carve out nanoscale designs on the surface of a new class of ionic polymer materials for the first time. The study provides new evidence that atomic force microscopy, or AFM, could be used to precisely fabricate materials needed for increasingly smaller devices.

Polymerized ionic liquids have potential applications in technologies such as lithium batteries, transistors and solar cells because of their high ionic conductivity and unique ...

UCLA researchers have developed a lens-free microscope that can be used to detect the presence of cancer or other cell-level abnormalities with the same accuracy as larger and more expensive optical microscopes.

The invention could lead to less expensive and more portable technology for performing common examinations of tissue, blood and other biomedical specimens. It may prove especially useful in remote areas and in cases where large numbers of samples need to be examined quickly.

The microscope is the latest in a series of computational imaging and diagnostic devices ...

VIDEO:

It's official -- our holiday lights are so bright we can see them from space. Thanks to the VIIRS instrument on the Suomi NPP satellite, a joint mission between NASA...

Click here for more information.

Even from space, holidays shine bright.

With a new look at daily data from the NOAA/NASA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) satellite, a NASA scientist and colleagues have identified how patterns in nighttime light intensity change during major holiday ...