(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- The best way to protect wild spinner dolphins in Hawaii while also maintaining the local tourism industry that depends on them is through a combination of federal regulations and community-based conservation measures, finds a new study from Duke University.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of tourists to Hawaii pay to have up-close encounters with the animals, swimming with them in shallow bays the dolphins use as safe havens for daytime rest. But as the number of tours increases, so do the pressures they place on the resting dolphins.

The Duke study says long-proposed federal regulations are urgently needed to limit daytime human access to these resting bays. But, it adds, a one-size-fits-all management approach will not work. Managing the bays should also include local community-based conservation measures, which can be tailored to how individual bays are used.

Together, these actions offer the best hope for protecting the dolphins while promoting the long-term sustainability of the local tourism industry, according to the study published this month in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism.

"Managing at the level of the bay, instead of focusing on the dolphins, has many advantages," said Heather Heenehan, a doctoral candidate at the Duke University Marine Laboratory, who led the study. "Most importantly, it explicitly acknowledges that all users of these bays have the right to take advantage of the resources they offer -- including dolphins, which are protected from harassment under federal law."

The five-year interdisciplinary study focused on Makako Bay and Kealakekua Bay on the Kona coast of Hawaii Island. The team conducted detailed assessments of how each bay was used, and the ways in which different groups of users interacted with and affected the dolphins.

Using an approach pioneered by the late Nobel Prize-winning social scientist Elinor Ostrom, they also assessed each bay for its potential to support community-based conservation efforts. These involve local residents working together to sustainably manage the resting bays as common-pool resources and to discourage human behaviors that can harm the dolphins.

At times, team members observed as many as 13 boats and 60 people coming within 700 feet of a pod of resting spinner dolphins. In some cases, people grabbed the animals and rode them, or put their dogs in the water to chase the dolphins.

Results showed that while daytime activities such as fishing, kayaking, swimming, recreational boating and dolphin tours -- all of which can disrupt dolphins -- occurred in both locations, the activity in Makako Bay was much more dolphin-centric, whereas Kealakekua Bay was used for a broader range of purposes.

Complicating matters further, Kealakekua scored twice as high as Makako on the 10-point scale of factors developed by Ostrom to identify locations where community-based conservation can emerge.

"This shows that a combination of management approaches is needed immediately to make interactions between humans and dolphins sustainable," said David Johnston, assistant professor of the practice of marine conservation ecology in Duke's Nicholas School of the Environment. "Neither top-down mandates nor bottom-up stakeholder efforts are the sole answer to this problem."

One key to community-driven protection of spinner dolphins, and a factor supported by Ostrom's work, is building common understanding of the resource through education and outreach, said Johnston, who previously worked with his students at Duke to create a free informational iPad app about spinner dolphin ecology and tourism called the Nai'a Guide.

Another key is building trust among users, something that will help improve adoption of new regulations.

"We're hoping this study contributes to a productive and constructive conversation with federal authorities and tourism operators in Hawaii about the impacts of dolphin tourism," said Xavier Basurto, assistant professor of sustainability science at Duke's Nicholas School of the Environment.

Future research on the possibility of community-based conservation for spinner dolphins could build on this work, Heenehan said. This could include surveys of different users to assess community views of the resource and gauge interest in existing and new community-led initiatives.

INFORMATION:

The new research was part of the Spinner Dolphin Acoustics, Population Parameters and Human Impacts Research (SAPPHIRE) Project, a joint effort between Duke University and Murdoch University in Western Australia. SAPPHIRE was supported by funding from NOAA, the Marine Mammal Commission, the State of Hawaii and Dolphin Quest.

Heenehan, Johnston and Basurto's co-authors on the new paper were Lars Bejder and Julian Tyne of the Murdoch University Cetacean Research Unit, and James E.S. Higham of the University of Otago's Department of Tourism.

CITATION: "Using Ostrom's Common-pool Resource Theory to Build toward an Integrated Ecosystem-based Sustainable Cetacean Tourism System in Hawaii," Heather Heenehan, Xavier Basurto, David W. Johnston, Duke University; Lars Bejder, Julian Tyne, Murdoch University Cetacean Research Unit; James E.S. Higham, University of Otago's Department of Tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Dec. 17, 2014. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2014.986490.

A new catalytic process is able to convert what was once considered biomass waste into lucrative chemical products that can be used in fragrances, flavorings or to create high-octane fuel for racecars and jets.

A team of researchers from Purdue University's Center for Direct Catalytic Conversion of Biomass to Biofuels, or C3Bio, has developed a process that uses a chemical catalyst and heat to spur reactions that convert lignin into valuable chemical commodities. Lignin is a tough and highly complex molecule that gives the plant cell wall its rigid structure.

Mahdi ...

A close look at the night sky reveals that stars don't like to be alone; instead, they congregate in clusters, in some cases containing as many as several million stars. Until recently, the oldest of these populous star clusters were considered well understood, with the stars in a single group having formed at different times, over periods of more than 300 million years. Yet new research published online today in the journal Nature suggests that the star formation in these clusters is more complex.

Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of researchers at the ...

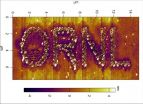

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Dec. 17, 2014--Scientists at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have used advanced microscopy to carve out nanoscale designs on the surface of a new class of ionic polymer materials for the first time. The study provides new evidence that atomic force microscopy, or AFM, could be used to precisely fabricate materials needed for increasingly smaller devices.

Polymerized ionic liquids have potential applications in technologies such as lithium batteries, transistors and solar cells because of their high ionic conductivity and unique ...

UCLA researchers have developed a lens-free microscope that can be used to detect the presence of cancer or other cell-level abnormalities with the same accuracy as larger and more expensive optical microscopes.

The invention could lead to less expensive and more portable technology for performing common examinations of tissue, blood and other biomedical specimens. It may prove especially useful in remote areas and in cases where large numbers of samples need to be examined quickly.

The microscope is the latest in a series of computational imaging and diagnostic devices ...

VIDEO:

It's official -- our holiday lights are so bright we can see them from space. Thanks to the VIIRS instrument on the Suomi NPP satellite, a joint mission between NASA...

Click here for more information.

Even from space, holidays shine bright.

With a new look at daily data from the NOAA/NASA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) satellite, a NASA scientist and colleagues have identified how patterns in nighttime light intensity change during major holiday ...

The sun emitted a mid-level solar flare, peaking at 11:50 p.m. EST on Dec. 16, 2014. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, which watches the sun constantly, captured an image of the event. Solar flares are powerful bursts of radiation. Harmful radiation from a flare cannot pass through Earth's atmosphere to physically affect humans on the ground, however -- when intense enough -- they can disturb the atmosphere in the layer where GPS and communications signals travel.

To see how this event may affect Earth, please visit NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center at http://spaceweather.gov, ...

In the first real-world trial of the impact of patient-controlled access to electronic medical records, almost half of the patients who participated withheld clinically sensitive information in their medical records from some or all of their health care providers.

This is the key finding of a new study by researchers from Clemson University, the Regenstrief Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine and Eskenazi Health published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Kelly Caine, assistant professor in Clemson's School of Computing, and colleagues at Clemson ...

A team of scientists, led by the University of Toronto's Barbara Sherwood Lollar, has mapped the location of hydrogen-rich waters found trapped kilometres beneath Earth's surface in rock fractures in Canada, South Africa and Scandinavia.

Common in Precambrian Shield rocks - the oldest rocks on Earth - the ancient waters have a chemistry similar to that found near deep sea vents, suggesting these waters can support microbes living in isolation from the surface.

The study, to be published in Nature on December 18, includes data from 19 different mine sites that were ...

Chemical modifications to DNA's packaging -- known as epigenetic changes -- can activate or repress genes involved in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and early brain development, according to a new study to be published in the journal Nature on Dec. 18.

Biochemists from NYU Langone Medical Center found that these epigenetic changes in mice and laboratory experiments remove the blocking mechanism of a protein complex long known for gene suppression, and transitions the complex to a gene activating role instead.

Researchers say their findings represent the first link ...

LA JOLLA, CA--December 17, 2014--Chemists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have invented a powerful method for joining complex organic molecules that is extraordinarily robust and can be used to make pharmaceuticals, fabrics, dyes, plastics and other materials previously inaccessible to chemists.

"We are rewriting the rules for how one thinks about the reactivity of basic organic building blocks, and in doing so we're allowing chemists to venture where none has gone before," said Phil S. Baran, the Darlene Shiley Chair in Chemistry at TSRI, whose laboratory reports ...