(Press-News.org) A study led by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators suggests that bariatric surgery can significantly reduce the risk of asthma attacks - also called exacerbations - in obese patients with asthma. Their report, published online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, is the first to find that significant weight reduction can reduce serious asthma-associated events.

"We found that, in obese patients with asthma, the risk of emergency department visits and hospitalizations for asthma exacerbations decreased by half in the two years after bariatric surgery," says Kohei Hasegawa, MD, MPH, MGH Department of Emergency Medicine, the lead author of the study. "Although previous studies of non-surgical weight loss interventions failed to show consistent results regarding asthma risks, our result strongly suggests that the kind of significant weight loss that often results from bariatric surgery can reduce adverse asthma events."

Both obesity and asthma are serious public health problems at historically high levels in the U.S., the authors note, and many researchers have associated obesity with the development of asthma and with an increased risk for asthma exacerbations. While previous studies investigating whether weight loss could reduce asthma risks showed little or no benefit, participants in those studies lost only modest amounts of weight. The current study was designed to investigate whether bariatric surgery - regarded as the most effective option for morbidly obese patients - might have a greater effect on asthma-associated risks.

Using available databases reflecting the utilization of health services in California, Florida and Nebraska - all three of which give access to deidentified information on individual patients - the research team identified 2,261 obese patients with asthma who underwent bariatric surgery from 2007 to 2009 and for whom information covering the two years before and after their surgery was available. This design, in which participants essentially act as their own controls, reduces the need to control for additional factors - such as age, gender, genetic background and physical activity - that might bias the results.

The analysis showed that, during the two years prior to surgery, around 22 percent of the studied patients had at least one emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization in each one-year period. In the two years after surgery, only 11 percent needed an ED visit or hospital admission in each year. Looking at hospitalization alone showed an even greater risk reduction, from around 7 percent per year to less than 3 percent. A comparison with patients who had other types of abdominal surgery showed that non-bariatric procedures had no impact on asthma exacerbation risk.

While the mechanism by which a significant weight loss can reduce asthma-associated risks is unknown, studies have linked obesity to increased inflammation, higher prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease, and physical changes in the airway - all of which could contribute to asthma severity. Hasegawa notes that a reduction or reversal of these mechanisms by bariatric surgery is plausible.

"The databases we had access to did not include the actual amount of weight lost by these patients, but it is well documented that bariatric surgery results in substantial weight loss, averaging around 35 percent of presurgical weight," he says. "While we can't currently say how much weight loss would be needed to reduce asthma risks, previous studies of non-surgical interventions indicate that modest weight loss is not enough."

"Bariatric surgery is a costly procedure that carries its own risks, factors that may offset the benefits regarding the risk of asthma exacerbation for some patients," Hasegawa adds. "To decrease asthma-related adverse events in the millions of obese individuals with asthma, we probably will need to develop safe, effective non-surgical approaches to achieve major weight loss."

INFORMATION:

Hasegawa is an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Additional co-authors of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology paper are senior author Carlos Camargo, MD, DrPH, MGH Emergency Medicine; Yuchiao Chang, PhD, MGH Department of Medicine; and Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, Harvard Interfaculty Initiative in Health Policy. The study was supported in part by an Eleanor and Miles Shore Fellowship grant from Harvard Medical School.

Massachusetts General Hospital , founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $760 million and major research centers in HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.

Media and popular culture might portray religion and science as being at odds, but new research from Rice University suggests just the opposite.

Findings from the recently completed study "Religious Understandings of Science (RUS)" reveal that despite many misconceptions regarding the intersection of science and religion, nearly 70 percent of evangelical Christians do not view the two as being in conflict with each other.

The research was presented by Rice sociologist Elaine Howard Ecklund today in Washington, D.C., during the American Association for the Advancement ...

Case Western Reserve researchers are part of an international team that has discovered that a common herpes drug reduces HIV-1 levels -- even when patients do not have herpes.

Published online in Clinical Infectious Diseases, the finding rebuts earlier scientific assumptions that Valacyclovir (brand name, Valtrex) required the presence of the other infection to benefit patients with HIV-1.

The result not only means that Valacyclovir can be used effectively with a broader range of HIV-1 patients, but also suggests promising new avenues for the development of HIV-fighting ...

Washington, D.C.-Two new papers from members of the MESSENGER Science Team provide global-scale maps of Mercury's surface chemistry that reveal previously unrecognized geochemical terranes -- large regions that have compositions distinct from their surroundings. The presence of these large terranes has important implications for the history of the planet.

The MESSENGER mission was designed to answer several key scientific questions, including the nature of Mercury's geological history. Remote sensing of the surface's chemical composition has a strong bearing on this and ...

Among the facts so widely assumed that they are rarely, if ever studied, is the notion that wider hips make women less efficient when they walk and run.

For decades, this assumed relationship has been used to explain why women don't have wider hips, which would make childbirth easier and less dangerous. The argument, known as the "obstetrical dilemma," suggests that for millions of years female humans and their bipedal ancestors have faced an evolutionary trade-off in which selection for wider hips for childbirth has been countered by selection for narrower hips for ...

WASHINGTON - A legal scholar and tobacco control expert says he has developed a research-based roadmap that allows for the immediate regulation of e-cigarettes.

Writing in the March issue of Food and Drug Law Journal, Eric N. Lindblom, JD, senior scholar at the O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, says his proposal would minimize the threats e-cigarettes pose to public health while still enabling them potentially help reduce smoking.

"This approach could help to heal the current split in the public health community over e-cigarettes by addressing ...

New research led by University of York scientists highlights how poor connectivity of protected area (PA) networks in Southeast Asia may prevent lowland species from responding to climate change.

Tropical species are shifting to higher elevations in response to rising temperatures, but there has been only limited research into the effectiveness of current protected area networks in facilitating such movements in the face of climate change.

However, the new study, published in the journal Biological Conservation, focuses on the connectivity of the protected area network ...

The font type of written text and how easy it is to read can be influential when it comes to engaging people with important health information and recruiting them for potentially beneficial programmes, new research by The University of Manchester and Leeds Beckett University has found.

Led by Dr Andrew Manley, a Chartered Sport and Exercise Psychologist and Senior Lecturer in Sport and Exercise Psychology at Leeds Beckett, the study - published in the latest issue of Patient Education and Counseling journal - assessed the extent to which the title and font of participant ...

With the socio-economic developments of the last decades, new emerging compounds have been produced, released and discharged through different point and diffuse sources in European rivers, lakes, and marine-coastal and transitional waters. Treated municipal wastewaters contain a multitude of organic chemicals including pharmaceuticals, hormones, and personal care products, which are continuously introduced into aquatic ecosystems. Their possible effects on the environment and human health is often unknown. The exposure of organisms, communities and humans to mixtures of ...

Although listening to music is common in all societies, the biological determinants of listening to music are largely unknown. According to a latest study, listening to classical music enhanced the activity of genes involved in dopamine secretion and transport, synaptic neurotransmission, learning and memory, and down-regulated the genes mediating neurodegeneration. Several of the up-regulated genes were known to be responsible for song learning and singing in songbirds, suggesting a common evolutionary background of sound perception across species.

Listening to music ...

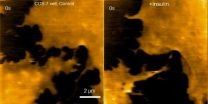

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a leading tool for imaging, measuring, and manipulating materials with atomic resolution - on the order of fractions of a nanometer.

AFM images surface topography of a structure by "touching" and "feeling" its surface by scanning an extremely fine needle (the diameter of the tip is about 5 nanometers, about 1/100 of light wavelength or 1/10,000 of a hair) on the surface.

This technique has been applied to image solid materials with nanometer resolution, but it has been difficult to apply AFM for a soft and large sample like eukaryotic ...