Is too much artificial light at night making us sick?

2015-03-18

(Press-News.org) Modern life, with its preponderance of inadequate exposure to natural light during the day and overexposure to artificial light at night, is not conducive to the body's natural sleep/wake cycle.

It's an emerging topic in health, one that UConn Health (University of Connecticut, Farmington, Conn.) cancer epidemiologist Richard Stevens has been studying for three decades.

"It's become clear that typical lighting is affecting our physiology," Stevens says. "But lighting can be improved. We're learning that better lighting can reduce these physiological effects. By that we mean dimmer and longer wavelengths in the evening, and avoiding the bright blue of e-readers, tablets and smart phones."

Those devices emit enough blue light when used in the evening to suppress the sleep-inducing hormone melatonin and disrupt the body's circadian rhythm, the biological mechanism that enables restful sleep.

Stevens and co-author Yong Zhu from Yale University explain the known short-term and suspected long-term impacts of circadian disruption in an invited article published in the British journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

"It's a new analysis and synthesis of what we know up to now on the effect of lighting on our health," Stevens says. "We don't know for certain, but there's growing evidence that the long-term implications of this have ties to breast cancer, obesity, diabetes, and depression, and possibly other cancers."

As smartphones and tablets become more commonplace, Stevens recommends a general awareness of how the type of light emitted from these devices affects our biology. He says a recent study comparing people who used e-readers to those who read old-fashioned books in the evening showed a clear difference - the e-readers showed delayed melatonin onset.

"It's about how much light you're getting in the evening," Stevens says. "It doesn't mean you have to turn all the lights off at 8 every night, it just means if you have a choice between an e-reader and a book, the book is less disruptive to your body clock. At night, the better, more circadian-friendly light is dimmer and, believe it or not, redder, like an incandescent bulb."

Stevens was on the scientific panel whose work led to the classification of shift work as a "probable carcinogen" by the International Agency on Cancer Research in 2007.

INFORMATION:

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B dates back to the 17th century. Its publisher claims it to be the world's first scientific journal.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-03-18

CORAL GABLES, Fla. (March 18, 2015) -- Come spring break, college students from all over the country travel to warmer climates for time off from school and to escape the cold weather. However, it's not all fun in the sun. At popular spring break destinations, fatalities from car crashes are significantly higher during the spring break weeks compared to other times of the year, according to a recent study published in the journal Economic Inquiry.

"We found that between the last week of February and the first week of April, a significantly greater number of traffic fatalities ...

2015-03-18

There's a carbon showdown brewing in the Arctic as Earth's climate changes. On one side, thawing permafrost could release enormous amounts of long-frozen carbon into the atmosphere. On the opposing side, as high-latitude regions warm, plants will grow more quickly, which means they'll take in more carbon from the atmosphere.

Whichever side wins will have a big impact on the carbon cycle and the planet's climate. If the balance tips in favor of permafrost-released carbon, climate change could accelerate. If the balance tips in favor of carbon-consuming plants, climate ...

2015-03-18

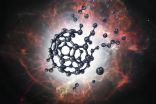

In 1996, a trio of scientists won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for their discovery of Buckminsterfullerene - soccer-ball-shaped spheres of 60 joined carbon atoms that exhibit special physical properties.

Now, 20 years later, scientists have figured out how to turn them into Buckybombs.

These nanoscale explosives show potential for use in fighting cancer, with the hope that they could one day target and eliminate cancer at the cellular level - triggering tiny explosions that kill cancer cells without affecting surrounding tissue.

"Future applications would probably ...

2015-03-18

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University cognitive scientist and collaborators have found that posture is critical in the early stages of acquiring new knowledge.

The study, conducted by Linda Smith, a professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, in collaboration with a roboticist from England and a developmental psychologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers a new approach to studying the way "objects of cognition," such as words or memories of physical objects, are tied to the position ...

2015-03-18

For generations, students have been taught the concept of "ecological succession" with examples from the plant world, such as the progression over time of plant species that establish and grow following a forest fire. Indeed, succession is arguably plant ecology's most enduring scientific contribution, and its origins with early 20th-century plant ecologists have been uncontested. Yet, this common narrative may actually be false. As posited in an article published in the March 2015 issue of The Quarterly Review of Biology, two decades before plant scientists explored the ...

2015-03-18

Tirat Carmel, Israel - March 19, 2015 - MeMed, Ltd., today announced publication of the results of a large multicenter prospective clinical study that validates the ability of its ImmunoXpert in-vitro diagnostic blood test to determine whether a patient has an acute bacterial or viral infection. The study enrolled more than 1,000 patients and is published in the March 18, 2015 online edition of PLOS ONE. Unlike most infectious disease diagnostics that rely on direct pathogen detection, MeMed's assay decodes the body's immune response to accurately characterize the cause ...

2015-03-18

The most extensive land-based study of the Amazon to date reveals it is losing its capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere. From a peak of two billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year in the 1990s, the net uptake by the forest has halved and is now for the first time being overtaken by fossil fuel emissions in Latin America.

The results of this monumental 30-year survey of the South American rainforest, which involved an international team of almost 100 researchers and was led by the University of Leeds, are published today in the journal Nature.

Over recent ...

2015-03-18

Messenger RNAs (mRNA) are linear molecules that contain instructions for producing the proteins that keep living cells functioning. A new study by UCL researchers has shown how the three-dimensional structures of mRNAs determine their stability and efficiency inside cells. This new knowledge could help to explain how seemingly minor mutations that alter mRNA structure might cause things to go wrong in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's.

mRNAs carry genetic information from DNA to be translated into proteins. They are generated as long chains of molecules, but ...

2015-03-18

Many people in the UK feel a strong sense of regional identity, and it now appears that there may be a scientific basis to this feeling, according to a landmark new study into the genetic makeup of the British Isles.

An international team, led by researchers from the University of Oxford, UCL (University College London) and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Australia, used DNA samples collected from more than 2,000 people to create the first fine-scale genetic map of any country in the world.

Their findings, published in Nature, show that prior to the mass ...

2015-03-18

DURHAM, N.C. -- Each year, rice in Asia faces a big threat from a sesame seed-sized insect called the brown planthopper. Now, a study reveals the molecular switch that enables some planthoppers to develop short wings and others long -- a major factor in their ability to invade new rice fields.

The findings will appear Mar. 18 in the journal Nature.

Lodged in the stalks of rice plants, planthoppers use their sucking mouthparts to siphon sap. Eventually the plants turn yellow and dry up, a condition called "hopper burn."

Each year, planthopper outbreaks destroy hundreds ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Is too much artificial light at night making us sick?