NASA sees Tropical Cyclone Nathan sporting hot towers, heavy rainfall

2015-03-18

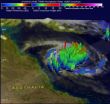

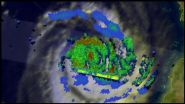

(Press-News.org) The TRMM satellite revealed that Tropical Cyclone Nathan had powerful thunderstorms known as "hot towers" near its center which are indicative of a strengthening storm.

Cyclone Nathan is located in the Coral Sea off Australia's Queensland coast. Nathan formed on March 10 near the Queensland coast triggering warnings there before moving east. Once out at sea, Nathan made a loop and headed back to Queensland.

On March 18, Nathan was nearing the Cape York Peninsula of Queensland. As a result warnings were in effect from Cape Melville to Innisfail, extending inland to Laura. Under watch is the area from Lockhart River to Cape Melville, extending inland to areas including Palmerville.

NASA-JAXA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite showed that the heaviest rainfall occurring in Tropical Cyclone Nathan on March 18 at 0758 UTC (3:58 a.m. EDT) was falling at a rate of over 119 mm (4.7 inches) on the eastern side of Nathan's eye. At NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, TRMM Precipitation Radar data were used to create a 3-D view of cyclone Nathan that showed storm heights in a rain band circling the storm's northwestern side reached heights of over 16 km (9.9 miles). Those data also showed "hot towers" or storm tops in Nathan's eyewall were reaching heights of over 13 km (8 miles).

"A "hot tower" is a tall cumulonimbus cloud that reaches at least to the top of the troposphere, the lowest layer of the atmosphere. It extends approximately nine miles (14.5 km) high in the tropics. These towers are called "hot" because they rise to such altitude due to the large amount of latent heat. Water vapor releases this latent heat as it condenses into liquid. NASA research shows that a tropical cyclone with a hot tower in its eyewall was twice as likely to intensify within six or more hours, than a cyclone that lacked a hot tower.

On Mar. 18 at 0900 UTC (5 a.m. EDT), the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) noted that Nathan had reached hurricane force with maximum sustained winds near 65 knots (75 mph/120.4 kph). It was centered near 14.9 south latitude and 148.9 east longitude, about 225 nautical miles (258.9 miles/416.7 km) east-northeast of Cairns, Queensland, Australia. It was moving to the west at 2 knots (2.3 mph/3.7 kph) and generating wave heights to 22 feet (6.7 meters).

The MODIS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured a visible image of Tropical Cyclone Nathan off the Queensland, Australia coast on March 18, 2015 at 04:15 UTC (12:15 a.m. EDT). The MODIS instrument showed a pinhole eye, about 5 nautical miles (5.7 miles/9.2 km) wide.

JTWC forecasters noted that Nathan is moving into an area of warm sea surface temperatures that will allow the storm to strengthen before making landfall on the Cape York Peninsula. JTWC forecasts call for Nathan to strengthen to 85 knots (97.8 mph/157.4 kph) by March 19 at 0600 UTC (2 a.m. EDT). For updated warnings and forecasts from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, visit: http://www.bom.gov.au/cyclone/.

It is forecast to make landfall north of Cairns on March 19 (by 1800 UTC) and move in a west-northwesterly direction across the Cape York Peninsula and into the Gulf of Carpentaria.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-03-18

Modern life, with its preponderance of inadequate exposure to natural light during the day and overexposure to artificial light at night, is not conducive to the body's natural sleep/wake cycle.

It's an emerging topic in health, one that UConn Health (University of Connecticut, Farmington, Conn.) cancer epidemiologist Richard Stevens has been studying for three decades.

"It's become clear that typical lighting is affecting our physiology," Stevens says. "But lighting can be improved. We're learning that better lighting can reduce these physiological effects. By that ...

2015-03-18

CORAL GABLES, Fla. (March 18, 2015) -- Come spring break, college students from all over the country travel to warmer climates for time off from school and to escape the cold weather. However, it's not all fun in the sun. At popular spring break destinations, fatalities from car crashes are significantly higher during the spring break weeks compared to other times of the year, according to a recent study published in the journal Economic Inquiry.

"We found that between the last week of February and the first week of April, a significantly greater number of traffic fatalities ...

2015-03-18

There's a carbon showdown brewing in the Arctic as Earth's climate changes. On one side, thawing permafrost could release enormous amounts of long-frozen carbon into the atmosphere. On the opposing side, as high-latitude regions warm, plants will grow more quickly, which means they'll take in more carbon from the atmosphere.

Whichever side wins will have a big impact on the carbon cycle and the planet's climate. If the balance tips in favor of permafrost-released carbon, climate change could accelerate. If the balance tips in favor of carbon-consuming plants, climate ...

2015-03-18

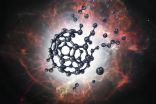

In 1996, a trio of scientists won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for their discovery of Buckminsterfullerene - soccer-ball-shaped spheres of 60 joined carbon atoms that exhibit special physical properties.

Now, 20 years later, scientists have figured out how to turn them into Buckybombs.

These nanoscale explosives show potential for use in fighting cancer, with the hope that they could one day target and eliminate cancer at the cellular level - triggering tiny explosions that kill cancer cells without affecting surrounding tissue.

"Future applications would probably ...

2015-03-18

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- An Indiana University cognitive scientist and collaborators have found that posture is critical in the early stages of acquiring new knowledge.

The study, conducted by Linda Smith, a professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, in collaboration with a roboticist from England and a developmental psychologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offers a new approach to studying the way "objects of cognition," such as words or memories of physical objects, are tied to the position ...

2015-03-18

For generations, students have been taught the concept of "ecological succession" with examples from the plant world, such as the progression over time of plant species that establish and grow following a forest fire. Indeed, succession is arguably plant ecology's most enduring scientific contribution, and its origins with early 20th-century plant ecologists have been uncontested. Yet, this common narrative may actually be false. As posited in an article published in the March 2015 issue of The Quarterly Review of Biology, two decades before plant scientists explored the ...

2015-03-18

Tirat Carmel, Israel - March 19, 2015 - MeMed, Ltd., today announced publication of the results of a large multicenter prospective clinical study that validates the ability of its ImmunoXpert in-vitro diagnostic blood test to determine whether a patient has an acute bacterial or viral infection. The study enrolled more than 1,000 patients and is published in the March 18, 2015 online edition of PLOS ONE. Unlike most infectious disease diagnostics that rely on direct pathogen detection, MeMed's assay decodes the body's immune response to accurately characterize the cause ...

2015-03-18

The most extensive land-based study of the Amazon to date reveals it is losing its capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere. From a peak of two billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year in the 1990s, the net uptake by the forest has halved and is now for the first time being overtaken by fossil fuel emissions in Latin America.

The results of this monumental 30-year survey of the South American rainforest, which involved an international team of almost 100 researchers and was led by the University of Leeds, are published today in the journal Nature.

Over recent ...

2015-03-18

Messenger RNAs (mRNA) are linear molecules that contain instructions for producing the proteins that keep living cells functioning. A new study by UCL researchers has shown how the three-dimensional structures of mRNAs determine their stability and efficiency inside cells. This new knowledge could help to explain how seemingly minor mutations that alter mRNA structure might cause things to go wrong in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's.

mRNAs carry genetic information from DNA to be translated into proteins. They are generated as long chains of molecules, but ...

2015-03-18

Many people in the UK feel a strong sense of regional identity, and it now appears that there may be a scientific basis to this feeling, according to a landmark new study into the genetic makeup of the British Isles.

An international team, led by researchers from the University of Oxford, UCL (University College London) and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute in Australia, used DNA samples collected from more than 2,000 people to create the first fine-scale genetic map of any country in the world.

Their findings, published in Nature, show that prior to the mass ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] NASA sees Tropical Cyclone Nathan sporting hot towers, heavy rainfall