INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Army Research Office, the Georgia Tech School of Biology and the Elizabeth Smithgall Watts Endowment. In addition to Goldman, Mendelson, Astley and Choset, the research team included Miguel Serrano, Patricio Vela and David L. Hu of Georgia Tech, and Chaohui Gong, Jin Dai and Matthew Travers of Carnegie Mellon.

About Carnegie Mellon University

Carnegie Mellon is a private, internationally ranked research university with programs in areas ranging from science, technology and business, to public policy, the humanities and the arts. More than 13,000 students in the university's seven schools and colleges benefit from a small student-to-faculty ratio and an education characterized by its focus on creating and implementing solutions for real problems, interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation. A global university, Carnegie Mellon has campuses in Pittsburgh, Pa., California's Silicon Valley and Qatar, and programs in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe and Mexico.

Carnegie Mellon's snake robots learn to turn by following the lead of real sidewinders

Research With Georgia Tech, Zoo Atlanta, provides insight into snake motion

2015-03-23

(Press-News.org) Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University who develop snake-like robots have picked up a few tricks from real sidewinder rattlesnakes on how to make rapid and even sharp turns with their undulating, modular device.

Working with colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Zoo Atlanta, they have analyzed the motions of sidewinders and tested their observations on CMU's snake robots. They showed how the complex motion of a sidewinder can be described in terms of two wave motions - vertical and horizontal body waves - and how changing the phase and amplitude of the waves enables snakes to achieve exceptional maneuverability.

"We've been programming snake robots for years and have figured out how to get these robots to crawl amidst rubble and through or around pipes," said Howie Choset, professor at CMU's Robotics Institute. "By learning from real sidewinders, however, we can make these maneuvers much more efficient and simplify user control. This makes our modular robots much more valuable as tools for urban search-and-rescue tasks, power plant inspections and even archaeological exploration."

Their findings are being published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Edition.

The work is a continuation of a collaboration between Howie Choset, CMU professor of robotics, Daniel Goldman, a Georgia Tech associate professor of physics, and Joseph Mendelson III, director of research at Zoo Atlanta. An earlier study, published on Oct. 10, 2014, in the journal Science, analyzed the ability of sidewinders to quickly climb sandy slopes. It showed that despite the snake's hundreds of body elements and thousands of muscles, the sidewinding motion could be simply modeled as a combination of a vertical and horizontal body wave.

With the model in hand and with a method to measure the movements of living snakes, the team, led by Henry Astley, a postdoctoral researcher in Goldman's group, was able to observe that sidewinders make gradual changes in direction by altering the horizontal wave while keeping the vertical wave constant. They also discovered that making a large phase shift in the vertical wave enabled the snake to make a sharp turn in the opposite direction.

Applying these controls to the robot allowed the robot to replicate the turns of the snake, while also simplifying control.

"By looking for insights in nature, we were able to dramatically improve the control and maneuverability of the robot," Astley said, "while at the same time using the robot as a tool to test the theorized control mechanisms of biological sidewinders."

The modular snake robot used in this study was specifically designed to pass horizontal and vertical waves through its body to move in three-dimensional spaces. The robot is two inches in diameter and 37 inches long; its body consists of 16 joints, each joint arranged perpendicular to the previous one. That allows it to assume a number of configurations and to move using a variety of gaits - some similar to those of a biological snake.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ascension of marine diatoms linked to vast increase in continental weathering

2015-03-23

Troy, N.Y. - A team of researchers, including Rensselaer professor Morgan Schaller, has used mathematical modeling to show that continental erosion over the last 40 million years has contributed to the success of diatoms, a group of tiny marine algae that plays a key role in the global carbon cycle. The research was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Diatoms consume 70 million tons of carbon from the world's oceans daily, producing organic matter, a portion of which sinks and is buried in deep ocean sediments. Diatoms account for over ...

Archaeologists discover Maya 'melting pot'

2015-03-23

Archaeologists working in Guatemala have unearthed new information about the Maya civilization's transition from a mobile, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary way of life.

Led by University of Arizona archaeologists Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan, the team's excavations of the ancient Maya lowlands site of Ceibal suggest that as the society transitioned from a heavy reliance on foraging to farming, mobile communities and settled groups co-existed and may have come together to collaborate on construction projects and participate in public ceremonies.

The findings, ...

Blood test can help identify stroke risk following heart surgery

2015-03-23

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - March 23, 2015 - The results of a blood test done immediately after heart surgery can be a meaningful indicator of postoperative stroke risk, a study by researchers at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center has found.

An acutely elevated level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) - a measure of kidney function detected through blood testing - was the most powerful predictor of postoperative stroke among the study's subjects.

Up to 9 percent of cardiac surgery patients suffer post-operative stroke, and these events are significantly more serious and more frequently ...

Metformin and vitamin D3 show impressive promise in preventing colorectal cancer

2015-03-23

The concept was simple: If two compounds each individually show promise in preventing colon cancer, surely it's worth trying the two together to see if even greater impact is possible.

In this instance, Case Western Reserve cancer researcher Li Li, MD, PhD, could not have been more prescient.

Not only did the combination of the two improve outcomes in animal studies, but the dual-compound effect was dramatically better than either option alone. Even better, these impressive results required only modest amounts of metformin and Vitamin D3, making concerns about side ...

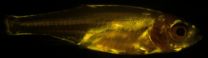

New gene influences apple or pear shape, risk of future disease

2015-03-23

DURHAM, N.C. - Scientists have known for some time that people who carry a lot of weight around their bellies are more likely to develop diabetes and heart disease than those who have bigger hips and thighs. But what hasn't been clear is why fat accumulates in different places to produce these classic "apple" and "pear" shapes.

Now, researchers have discovered that a gene called Plexin D1 appears to control both where fat is stored and how fat cells are shaped, known factors in health and the risk of future disease.

Acting on a pattern that emerged in an earlier study ...

Experiments reveal key components of the body's machinery for battling deadly tularemia

2015-03-23

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. -- MARCH 23, 2015) Research led by scientists at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital has identified key molecules that trigger the immune system to launch an attack on the bacterium that causes tularemia. The research was published online March 16 in Nature Immunology.

The team, led by Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti, Ph.D., a member of the St. Jude Department of Immunology, found key receptors responsible for sensing DNA in cells infected by the tularemia-causing bacterium, Francisella. Tularemia is a highly infectious disease that kills more than 30 percent ...

Cerebellar ataxia can't be cured, but some cases can be treated

2015-03-23

MAYWOOD, Ill. - No cures are possible for most patients who suffer debilitating movement disorders called cerebellar ataxias.

But in a few of these disorders, patients can be effectively treated with regimens such as prescription drugs, high doses of vitamin E and gluten-free diets, according to a study in the journal Movement Disorders.

"Clinicians must become familiar with these disorders, because maximal therapeutic benefit is only possible when done early. These uncommon conditions represent a unique opportunity to treat incurable and progressive diseases," first ...

Quantum correlation can imply causation

2015-03-23

Contrary to the statistician's slogan, in the quantum world, certain kinds of correlations do imply causation.

Research from the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) at the University of Waterloo and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics shows that in quantum mechanics, certain kinds of observations will let you distinguish whether there is a common cause or a cause-effect relation between two variables. The same is not true in classical physics.

Explaining the observed correlations among a number of variables in terms of underlying causal mechanisms, known ...

Rett Syndrome Research Trust awards $1.3 million for clinical trial

2015-03-23

A surgical sedative may hold the key to reversing the devastating symptoms of a neurodevelopmental disorder found almost exclusively in females. Ketamine, used primarily for operative procedures, has shown such promise in mouse models that Case Western Reserve and Cleveland Clinic researchers soon will launch a two-year clinical trial using low doses of the medication in up to 35 individuals with Rett Syndrome.

The $1.3 million grant from Rett Syndrome Research Trust (RSRT) represents a landmark step in area researchers' efforts to create a true regional collaborative ...

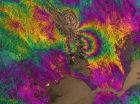

3-D satellite, GPS earthquake maps isolate impacts in real time

2015-03-23

When an earthquake hits, the faster first responders can get to an impacted area, the more likely infrastructure--and lives--can be saved.

New research from the University of Iowa, along with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), shows that GPS and satellite data can be used in a real-time, coordinated effort to fully characterize a fault line within 24 hours of an earthquake, ensuring that aid is delivered faster and more accurately than ever before.

Earth and Environmental Sciences assistant professor William Barnhart used GPS and satellite measurements from ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

Could “cyborg” transplants replace pancreatic tissue damaged by diabetes?

Hearing a molecule’s solo performance

Justice after trauma? Race, red tape keep sexual assault victims from compensation

Columbia researchers awarded ARPA-H funding to speed diagnosis of lymphatic disorders

James R. Downing, MD, to step down as president and CEO of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in late 2026

A remote-controlled CAR-T for safer immunotherapy

UT College of Veterinary Medicine dean elected Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology

AERA selects 34 exemplary scholars as 2026 Fellows

Similar kinases play distinct roles in the brain

New research takes first step toward advance warnings of space weather

Scientists unlock a massive new ‘color palette’ for biomedical research by synthesizing non-natural amino acids

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

[Press-News.org] Carnegie Mellon's snake robots learn to turn by following the lead of real sidewindersResearch With Georgia Tech, Zoo Atlanta, provides insight into snake motion