(Press-News.org) Lung diseases like emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis are common among people with malfunctioning telomeres, the "caps" or ends of chromosomes. Now, researchers from Johns Hopkins say they have discovered what goes wrong and why.

Mary Armanios, M.D., an associate professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine., and her colleagues report that some stem cells vital to lung cell oxygenation undergo premature aging -- and stop dividing and proliferating -- when their telomeres are defective. The stem cells are those in the alveoli, the tiny air exchange sacs where blood takes up oxygen.

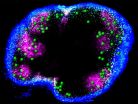

In studies of these isolated stem cells and in mice, Armanios' team discovered that dormant or senescent stem cells send out signals that recruit immune molecules to the lungs and cause the severe inflammation that is also a hallmark of emphysema and related lung diseases.

Until now, Armanios says, researchers and clinicians have thought that "inflammation alone is what drives these lung diseases and have based therapy on anti-inflammatory drugs for the last 30 years."

But the new discoveries, reported March 30 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest instead that "if it's premature aging of the stem cells driving this, nothing will really get better if you don't fix that problem," Armanios says.

Acknowledging that there are no current ways to treat or replace damaged lung stem cells, Armanios says that knowing the source of the problem can redirect research efforts. "It's a new challenge that begins with the questions of whether we take on the effort to fix this defect in the cells, or try to replace the cells," she adds.

Armanios and her team say their study also found that this telomere-driven defect leaves mice extremely vulnerable to anticancer drugs like bleomycin or busulfan that are toxic to the lungs. The drugs and infectious agents like viruses kill off the cells that line the lung's air sacs. In cases of telomere dysfunction, Armanios explains, the lung stem cells can't divide and replenish these destroyed cells.

When the researchers gave these drugs to 11 mice with the lung stem cell defect, all became severely ill and died within a month.

This finding could shed light on why "sometimes people with short telomeres may have no signs of pulmonary disease whatsoever, but when they're exposed to an acute infection or to certain drugs, they develop respiratory failure," says Armanios. "We don't think anyone has ever before linked this phenomenon to stem cell failure or senescence."

In their study, the researchers genetically engineered mice to have a telomere defect that impaired the telomeres in just the lung stem cells in the alveolar epithelium, the layer of cells that lines the air sacs. "In bone marrow or other compartments, when stem cells have short telomeres, or when they age, they just die out," Armanios says. "But we found that instead, these alveolar cells just linger in the senescent stage."

The stem cells stayed alive but were unable to divide and regenerate the epithelial lining in the air sacs. After two weeks, the senescent lung stem cells only generated five new epithelial structures per 5,000 stem cells, compared to an average of 425 structures from 5,000 healthy stem cells.

The researchers say they also hope to learn more about how mice with this telomere defect in lung stem cells respond to cigarette smoke. Other studies of patients with telomere defects, including one published last year by Armanios and her colleagues, suggest that telomere defects may be one of the more common predisposing factors to lung diseases, such as emphysema.

Further studies should help the scientists determine whether cigarette smoke causes lung disease in this setting because of stem cell failure, says Armanios.

INFORMATION:

Other scientists who contributed to the study include Jonathan K. Alder, Nathachit Limjunyawong, Susan E. Stanley, Frant Kembou and Wayne Mitzner from Johns Hopkins; Christina E. Barkauskas and Brigid L.M. Hogan from Duke University School of Medicine; and Rubin M. Tuder from the University of Colorado Denver.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health (K99 HL113105, K08 HL122521, PO1 CHL10342, RO1 HL119476), the Ellison Medical Foundation and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute.

Media Contacts:

Vanessa Wasta, 410-614-2916, wasta@jhmi.edu

Amy Mone, 410-614-2915, amone@jhmi.edu

Increasing state alcohol taxes could prevent thousands of deaths a year from car crashes, say University of Florida Health researchers, who found alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes decreased after taxes on beer, wine and spirits went up in Illinois.

A team of UF Health researchers discovered that fatal alcohol-related car crashes in Illinois declined 26 percent after a 2009 increase in alcohol tax. The decrease was even more marked for young people, at 37 percent.

The reduction was similar for crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers and extremely drunken drivers, ...

Soil organic matter, long thought to be a semi-permanent storehouse for ancient carbon, may be much more vulnerable to climate change than previously thought.

Plants direct between 40 percent and 60 percent of photosynthetically fixed carbon to their roots and much of this carbon is secreted and then taken up by root-associated soil microorganisms. Elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in the atmosphere are projected to increase the quantity and alter the composition of root secretions released into the soil.

In new research in the March 30 edition of the journal, ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Sitting in traffic during rush hour is not just frustrating for drivers; it also adds unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere.

Now a study by researchers at MIT could lead to better ways of programming a city's stoplights to reduce delays, improve efficiency, and reduce emissions.

The new findings are reported in a pair of papers by assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering Carolina Osorio and alumna Kanchana Nanduri SM '13, published in the journals Transportation Science and Transportation Research: Part B. In these ...

Australian scientists have discovered a new population of 'memory' immune cells, throwing light on what the body does when it sees a microbe for the second time. This insight, and others like it, will enable the development of more targeted and effective vaccines.

Two of the key players in our immune systems are white blood cells known as 'T cells' and 'B cells'. B cells make antibodies, and T cells either help B cells make antibodies, or else kill invading microbes. B cells and killer T cells are known to leave behind 'memory' cells to patrol the body, after they have ...

At some point, probably 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, humans began talking to one another in a uniquely complex form. It is easy to imagine this epochal change as cavemen grunting, or hunter-gatherers mumbling and pointing. But in a new paper, an MIT linguist contends that human language likely developed quite rapidly into a sophisticated system: Instead of mumbles and grunts, people deployed syntax and structures resembling the ones we use today.

"The hierarchical complexity found in present-day language is likely to have been present in human language since its emergence," ...

Alcoholism takes a toll on every aspect of a person's life, including skin problems. Now, a new research report appearing in the April 2015 issue of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology, helps explain why this happens and what might be done to address it. In the report, researchers used mice show how chronic alcohol intake compromises the skin's protective immune response. They also were able to show how certain interventions may improve the skin's immune response. Ultimately, the hope is that this research could aid in the development of immune-based therapies to combat skin ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. -- Increasing state alcohol taxes could prevent thousands of deaths a year from car crashes, say University of Florida Health researchers, who found alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes decreased after taxes on beer, wine and spirits went up in Illinois.

A team of UF Health researchers discovered that fatal alcohol-related car crashes in Illinois declined 26 percent after a 2009 increase in alcohol tax. The decrease was even more marked for young people, at 37 percent.

The reduction was similar for crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers and extremely ...

A history of depression may put women at risk for developing diabetes during pregnancy, according to research published in the latest issue of the Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing by researchers from Loyola University Chicago Marcella Niehoff School of Nursing (MNSON). This study also pointed to how common depression is during pregnancy and the need for screening and education.

"Women with a history of depression should be aware of their risk for gestational diabetes during pregnancy and raise the issue with their doctor," said Mary Byrn, PhD, RN, ...

WASHINGTON, DC, March 31, 2015 -- People whose sexual identities changed toward same-sex attraction in early adulthood reported more symptoms of depression in a nationwide survey than those whose sexual orientations did not change or changed in the opposite direction, according to a new study by a University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) sociologist.

The study, "Sexual Orientation Identity Change and Depressive Symptoms: A Longitudinal Analysis," which appears in the current issue of the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people ...

This news release is available in French. Domestic violence takes many forms. The control of a woman's reproductive choices by her partner is one of them. A major study published in PLOS One, led by McGill PhD student Lauren Maxwell, showed that women who are abused by their partner or ex-partner are much less likely to use contraception; this exposes them to sexually transmitted diseases and leads to more frequent unintended pregnancies and abortions. These findings could influence how physicians provide contraceptive counselling.

Negotiating for contraception

A ...